The first magnified photo of a dying star outside our galaxy indicates a violent end

WOH G64 is a red supergiant 160,000 light-years from Earth demonstrating erratic behavior over the last decade

160,000 light-years from planet Earth, a giant star is in agony. It could be on the verge of death, which means it expels huge amounts of gas and dust in a chaotic cosmic dance. Everything seems to indicate that it is in the last stages of its life before becoming a supernova. When that happens, one of the most energetic events in the universe will occur: the star will briefly release an enormous amount of light and energy and then go out forever.

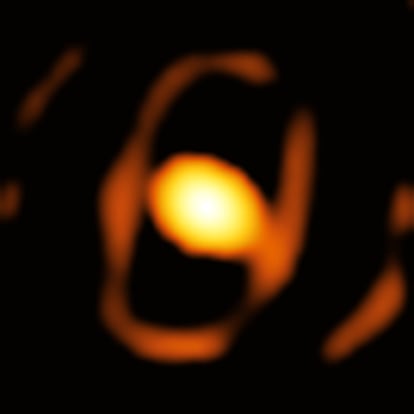

We know this because scientists have seen it in the first high-resolution photograph, in astronomical terms, of a star outside our galaxy. Known as WOH G64, it was captured thanks to the gravity instrument of the Very Large Telescope (VLT) from the European Southern Observatory (ESO), located in the Chilean region of Antofagasta. The photo and the accompanying research were published Thursday, November 21, in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Keiichi Ohnaka, an astrophysicist at the Andrés Bello University in Chile and lead author of the research, says, “for the first time, it has been possible to capture a magnified image of a dying red supergiant in a galaxy other than the Milky Way.” To achieve this, Ohnaka and his team had to get creative. Because the star is so far away, no single telescope is capable of capturing it with sufficient sharpness.

If the scientists had wanted to take the image with a single instrument, they would have had to use a gigantic telescope at least 100 meters in diameter. “This technology does not exist; it would be very expensive and technically difficult to use,” explains Ohnaka. The largest telescopes available today are between eight and 10 meters in diameter. A larger one cannot be built because its lenses would be so heavy they would deform, spoiling its optics. Faced with this dilemma, the astronomers have chosen to combine the power of four telescopes, each 1.8 meters in diameter.

They mixed the light received individually by each of the devices, combined the data, and so managed to obtain an image with an unprecedented level of sharpness for the exploration of stars outside our galaxy. But the research yielded a snapshot that was not exactly what the scientists had expected.

A dramatic end

WOH G64 is 2,000 times the size of our Sun and lies in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf galaxy orbiting the Milky Way. Between 2005 and 2007, Ohnaka’s team first observed it with a telescope in the Atacama Desert and were able to learn more about the star’s characteristics, such as its brightness and composition. Using computer models, they were able to reconstruct the appearance of the red supergiant. This reconstruction of the star looks nothing like the actual photograph.

In the new image, an accumulation of light can be seen enveloping the star in an oval shape, as if it were an egg, surrounded by a ring. The authors of the study believe that this is due to huge amounts of matter that the star is ejecting into space. “The evidence shows us that WOH G64 has changed in the last 10 years,” Ohnaka explains, adding, “I don’t know exactly when it happened, but it started expelling more and more matter.” The normal thing for such a star, he explains, is for the ejection to be geometric, similar to a soap bubble, and not oval, which caused some confusion.

There are several possible explanations for this phenomenon, explains Yolanda Jiménez Teja, a postdoctoral researcher at the Andalusian Astrophysics Institute, who specializes in stars outside the Milky Way. “As a red supergiant, it has three or four potential fates, all equally dramatic,” she explains.

One possibility is that WOH G64 is breaking up. During the advanced stages of its life, the outer atmosphere of stars like the Sun expands and can gradually break away, forming planetary nebulae. Its current behavior could also be due to its instability, causing jets of matter to be ejected violently through an axis that gives it its egg shape. Another hypothesis suggests that the energy cocoon is being generated by the gravitational influence of a companion star that has not yet been discovered because of a weaker brightness, overshadowed by that of the main star.

“There are two other possibilities,” says Jiménez. “One is that the star increases its temperature and is in the process of becoming a blue supergiant, a last vital phase before dying. The other is that it transforms into a black hole. These processes take place over thousands of years. It is impressive that we are seeing all these variations in just a decade, a blink of an eye in universe time. It seems that they have caught the star in a moment of great activity and that is very valuable,” she adds.

It is not yet certain what will happen to WOH G64. It could die, transform, or even, after this massive ejection of matter, recover its previous equilibrium. It could be tens to thousands of years before we see the outcome. Jacco van Loon, director of the Keele Observatory in the UK, and co-author of the study, has been observing WOH G64 since the 1990s and believes that “this star is one of the most extreme of its kind, and any drastic change could bring it close to an explosive end.”

More observations are needed to fully understand it. What is certain, says Gerd Weigelt, professor of astronomy at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy and co-author of the study, is that the phenomenon “provides a unique opportunity to witness the life of a star in real time.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.