A repeat of the 1829 Torrevieja earthquake could kill thousands due to area’s tourism boom

A study analyzes the enormous impact of earthquakes on the Mediterranean city, where the population has multiplied sixfold

On Christmas Day in 1884, the earth shook for a long 20 seconds in Spain. Many clocks stopped at the hour of the catastrophe, around 9 p.m. In the city of Málaga, thousands of people fled in terror from theaters and cafés. But the worst of the disaster struck 100 inland mountain villages.

Arenas del Rey, located on sandy soil, completely collapsed, along with its 400 houses. Most families were at home having dinner and celebrating the holiday. That day, about 900 people died, and another 2,000 were injured. It was the last major earthquake in Spain’s history, and the first to spark an unprecedented international aid campaign for the victims, who lived months of terror due to the frequent aftershocks. More than 140 years later, scientists are certain that an earthquake like the one that struck in 1884 will happen again sooner or later, although it is impossible to know when.

A team of geologists has analyzed the potential impact of a similar earthquake if it occurred today. In addition to the Arenas del Rey quake, they also researched the 1829 Torrevieja earthquake, which killed nearly 400 people and forced the relocation of five entire towns — Guardamar, Torrevieja, Almoradí, Rojales, and Benejúzar.

The current estimates are chilling. The area affected by the Torrevieja earthquake is now one of the most densely populated tourist hubs in the country. In these places, the resident population has multiplied sixfold, and the number of people present increases several times over during peak tourist seasons. Based on the updated population data for this area from Spain’s National Institute of Statistics (INE) in 2024, an earthquake like the one in the 19th century would cause around 5,000 deaths with a 60% probability. During the summer season, the number could rise to 11,000. Economic losses would be around €100 billion ($117 billion).

“We are aware that these estimates are terrifying, but we have been very careful in applying the models and have always taken the most conservative ones,” explains Javier Élez, a researcher at the University of Salamanca and first author of the study.

These calculations were developed using the tool used by the United States Geological Survey to estimate the impact of severe earthquakes worldwide based on their intensity. The system is called PAGER, which stands for Prompt Assessment of Global Earthquakes for Response. Spanish scientists have modified it to include updated population data and the geological characteristics of Spain. The system — which also uses satellite imagery — allows for an initial assessment in a matter of minutes.

“Earthquake estimations always work with probabilities,” explains Pablo Silva, professor of Geological Hazards at the University of Salamanca and co-author of the work, which is published in the specialized journal Natural Hazards. “If you ask me if these earthquakes will happen again in a few years, the risk is low. But if we consider 250 years, the probability would be almost 100%,” he warns. This tool, he says, can help the country “be prepared for catastrophes that we know are going to happen again, and be able to react better to them.”

In the Torrevieja earthquake, it was very difficult to rescue the population because all the wooden bridges over the Segura River collapsed, leaving the southern bank cut off. “In a modern earthquake, it’s crucial for emergency services to know which access and evacuation routes would be available based on the geological characteristics of the terrain,” Silva adds. “Urban expansion and the rampant tourism development in the southern part of Alicante increase the area’s vulnerability to extreme geological events by 400%.”

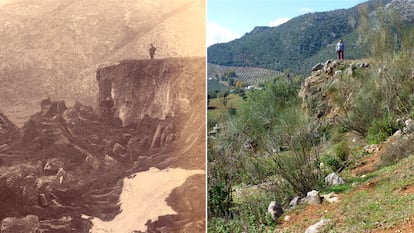

“In the Arenas del Rey earthquake, entire farmhouses were displaced 200 meters due to landslides,” explains Miguel Ángel Rodríguez-Pascua, a geologist at the Spanish Geological and Mining Institute (IGME-CSIC), who is a co-author of the study. That was one of the few historic earthquakes that left scars — landslides, cracks — that are still visible today. “These sites are part of our national geological heritage, and they can also be the perfect place to train emergency units,” he explains. During the Torrevieja earthquake, a phenomenon known as liquefaction occurred: a seismic process in which the ground literally dissolves, swallowing buildings and their occupants whole.

The two cases are located in the most seismically active region of Spain. In all the scenarios analyzed, international assistance would be required, and in many cases, the country would face human and economic losses for which it is “not prepared,” the report warns.

Rodríguez-Pascua and other IGME scientists are part of the Geological Emergency Response Unit, which has collaborated with the Military Emergency Unit in disasters such as the La Palma volcano eruption and the torrential rains in Valencia. The scientists designed earthquake scenarios for two large drills in Seville (2016) and Murcia (2018), simulating quakes with a magnitude of 6.5 — similar to the historical earthquakes in Arenas del Rey and Torrevieja. The team has been developing tools tailored to the Iberian Peninsula’s unique geological and geodynamic characteristics since 2012, with funding from the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities.

The authors believe that Spain lives “with a false sense of security” regarding seismic risk. This is because there have been few serious earthquakes in recent history. The last significant one was the Lorca earthquake in 2011, which measured 5.2 magnitude and caused nine deaths, 300 injuries, and losses of approximately €500 million ($585 million). There’s a whole branch of seismology dedicated to identifying archaeological traces of prehistoric earthquakes in order to expand the statistical record and better understand what the future might hold.

Part of the scientific team has contributed to the recently approved National Monitoring Plan for Seismic, Volcanic, and Other Geophysical Phenomena. The plan, led by the National Geographic Institute (IGN) —the body in charge of seismic risk monitoring in Spain under the Ministry of Transport and Mobility — proposes 58 measures to reinforce surveillance networks for destructive natural events like earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, and solar storms. One of IGME’s proposals was to create a comprehensive map of all active faults in the country, explains Rodríguez-Pascua. With that map, Spain could begin using the PAGER system to make risk estimates for specific localities.

“It’s undoubtedly a useful tool that can give a very good idea of the range of casualties and economic losses faced,” says Juan Vicente Cantavella, head of the National Seismic Network at the IGN. Despite the model’s limitations — chiefly the lack of statistical data on large earthquakes in Spain due to their rarity — he views it positively.

Another shortcoming is the insufficient data on building characteristics in each area, which is crucial for assessing real risk: a village of adobe homes faces very different hazards than one built with reinforced concrete. The IGN’s seismic risk maps are based on past earthquake records. “In any calculation,” explains Cantavella, “even if there is a low probability of a major earthquake in, say, 50 years, there is always an assumed risk.”

“This is a necessary, interesting, and well-conducted study,” says Álvaro González, a geologist specializing in earthquakes at the Barcelona Center for Mathematical Research. “The serious human and economic losses estimated by this study are unfortunately reasonable and demonstrate the importance of being prepared for similar events,” the researcher adds.

Twenty years ago, using less precise techniques, González estimated that there would be significant human losses if earthquakes of the same magnitude as the Torrevieja or Arenas del Rey quakes were to occur again.

He explains: “This type of research is necessary to give us an idea of the possible consequences and to raise awareness of the need to be more resilient to these events: where buildings should be rehabilitated to make them more resistant, what resources should be prepared for emergencies, how to educate the population on how to protect themselves, and what financial resources should be available for relief and reconstruction.”

“Large earthquakes, due to their fortunate rarity, are gradually fading from the collective memory,” he continues. “And it is necessary to warn that there is still the threat of another destructive earthquake, and it is only a matter of time before another one occurs.”

In 2013, González drew attention to this problem in a letter to the editor of EL PAÍS, discussing the earthquake that destroyed Lisbon in 1755 and killed thousands of people in Spain and Portugal. “The survival and well-being of future generations in Spain will depend on how well we are able to research, prevent, and educate about natural hazards today,” he wrote.

Estimates for a present-day earthquake similar to the Arenas del Rey event tell a different story. None of the modeled scenarios show death tolls approaching those of the 1884 quake, which occurred 141 years ago. One reason, according to University of Salamanca professor Pablo Silva, is the depopulation of the Granada mountain regions. Another is that the original quake struck at a time when nearly everyone was at home.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.