Enigmatic ‘dragon man’ was not a new human species, but a Denisovan

DNA and protein analysis of a 146,000-year-old skull shows for the first time what the face of this species, which occupied much of Asia and left its genes in modern humans, was like

After 146,000 years and a far-fetched history, a team led by Chinese scientists and a Swedish Nobel Prize winner in medicine announced Wednesday that it has successfully recovered DNA from a fossil assigned to a new human species, Homo longi, popularly known as the “dragon man.” This exceptional breakthrough overturns one of the last major discoveries in human evolution: it turns out that Homo longi is not a new human species native to Asia, but a Denisovan.

Denisovans are the only human species identified not by the shape of their bones and skull, but by DNA extracted from tiny bone fragments found in the Denisova Caves in Russia. It was the tip of a little girl’s pinky finger that led to the discovery of this new human group, and subsequent samples revealed them to be a sister species to the Neanderthals. Genetics also showed that they had sex and fertile children with Neanderthals, and with our own species, Homo sapiens. Today, many Asians carry a small percentage of Denisovan DNA within them. Among the inherited genes are those that allow people to breathe without suffocating in the highest altitudes on the planet, such as the Himalayas, and others that improve metabolism in extreme cold, present in the Inuit of the Arctic.

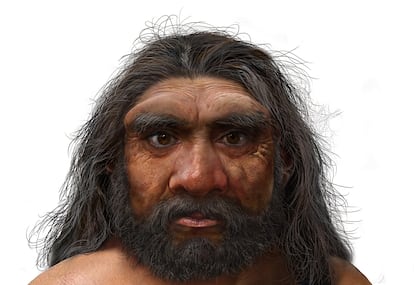

What no one yet knew was what these early humans’ faces looked like, as no complete skulls had been found. The study published Wednesday changes this, showing that the Denisovans were robust people, with large teeth and very pronounced eyebrows. They probably also had a brain equal to or larger than that of modern humans, judging by their cranial capacity of 1,400 cubic centimeters.

The molecular identification of this first skull confirms that the Denisovans were a successful group, surviving for tens of thousands of years in very diverse environments in Asia, from the steppes of Siberia through the Himalayas to the coasts of eastern China, including Taiwan. In these and other places, such as Laos, fossils have been found that possibly also belong to this third branch of humanity, as suggested by the authors of the study, published in Cell.

The species Homo longi must therefore be discarded, and we must even stop thinking about species when talking about human evolution, Svante Pääbo, a world pioneer in ancient DNA analysis, Nobel Prize winner in Medicine in 2022, and co-author of the work, tells EL PAÍS. “The concept of species is no longer useful when talking about Neanderthals and Denisovans. They are closely related groups that interbred and had fertile children among themselves, and also with our species. So we prefer to talk about modern humans [us], Neanderthals, and Denisovans,” he explains in an email.

The team focused their analysis on the Harbin cranium, whose story begins in 1933, when Japanese troops invaded China. A worker collaborating with the Japanese on the construction of a bridge near the city of Harbin came across the fossil, hid it from his bosses, and kept it in a well for the rest of his life, as after the war he refused to reveal to the communist authorities that he had collaborated with the invaders. In 2018, this man’s grandchildren recovered the fossil and took it to paleoanthropologist Qiang Ji, who welcomed it as a treasure, as it had survived the Japanese invasion, a civil war, the communist dictatorship, Mao’s Cultural Revolution, and rampant fossil trafficking in China. The problem was that there seemed to be no way to confirm its provenance or its age.

Four years ago, Ji’s team managed to date the skull thanks to the mud stuck to its nostrils. It was 146,000 years old and identical to the sediments beneath the Harbin Bridge. The researchers announced that the fossil represented a new “sister” species of Homo sapiens, a scientific coup that didn’t convince all experts.

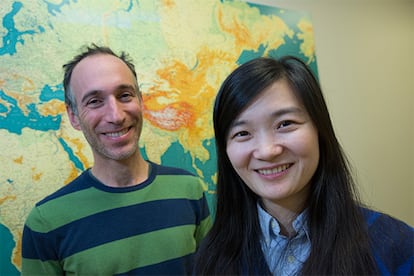

The lead author of the new study is 42-year-old Chinese paleoanthropologist Qiaomei Fu, whose participation has been key. The scientist learned the best techniques for analyzing ancient DNA in Pääbo’s laboratory at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and in that of American David Reich at Harvard University, another leader in this field. The researcher now leads her own team at the Institute of Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and collaborates with Qiang Ji’s team. After several failed attempts to isolate DNA from bone, the team managed to rescue mitochondrial DNA from the tartar accumulated on one of its molars. The results confirm that the dragon man is actually a Denisovan related to its Siberian counterparts.

Fu led another study, also published Wednesday in Science, in which researchers managed to recover 95 proteins from that same skull. This biological material, more resistant than DNA over time, confirms the theory that it is a Denisovan, and sets a world record: they have recovered more proteins from a single human fossil than all similar studies conducted to date.

“Denisovans are the new star of human evolution,” summarizes paleoanthropologist Antonio Rosas of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), who did not participate in either study, and who emphasizes their importance. The key, he explains, is that for the first time these humans have “a skull associated in a seemingly indubitable way,” that is, a face. “This first Denisovan par excellence,” he explains, “can be used to analyze other classic and enigmatic fossils, such as the Dali skull, some 270,000 years old.” The human fossils from Hualongdong, in eastern China, dating back 300,000 years, and the juluensis, or big-headed people, who lived in northern and central China at the same time, could also be Denisovan. A few weeks ago, another team managed to recover proteins from a jawbone found in Taiwan. The analysis revealed that it was from a Denisovan, which may have lived in two eras when this territory was connected to continental Asia. It could be between 190,000 and 130,000 years old, or between 70,000 and just 10,000 years old.

British paleoanthropologist Chris Stringer, co-author of the study that established the dragon man as a new species, hasn’t given up on his thesis. “These two articles are potentially very important, although a more complete assessment will be necessary by experts in ancient DNA and proteomics,” he responded to EL PAÍS in an email. “I have been collaborating with Chinese scientists on new morphological analyses of human fossils, including the one from Harbin, and this work makes it increasingly likely that this is the most complete Denisovan fossil found so far, and that Homo longi is the appropriate species name for this group.” “Another name, Homo juluensis, was recently coined to include Denisovans but not Harbin, so it is unlikely to be appropriate for either. Our analyses suggest that most large-cranial humans of the past 800,000 years can be classified into one or other of the following groups or species: Asian Homo erectus, Heidelbergensis, Neanderthals, sapiens, and Denisovans-longi,” he adds.

When and where Denisovans and Neanderthals appeared, and who their ancestors were, remains a mystery. The most likely scenario is that they were some variant of Homo erectus, the longest-lived human species and the first to leave Africa, already walking on two legs. Sapiens also descend from Homo erectus, although our origin is confirmed to be in Africa.

“The million-dollar question,” says Rosas, is why the Denisovans of Asia, like their Neanderthal brethren in Europe, became extinct around 40,000 years ago, just as large groups of Sapiens arrived from Africa. That period of ice ages was extremely harsh, and caused the gradual extinction of mammoths and other large mammals, the hunting of which Neanderthals and Denisovans lived on. Despite becoming extinct in Europe several times, Sapiens thrived, becoming the only human species on Earth. The CSIC scientist believes, like other experts, that the key lay in “the new neural capacities of Sapiens involved in creating and maintaining large-scale cooperative networks”; a characteristic that has yet to be demonstrated in the other two branches of humanity.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.