Each person has a unique breathing pattern that’s as distinctive as fingerprints or voice

This distinctive feature could reveal information about an individual’s physical and mental health

Inhale and exhale: that’s your respiratory fingerprint. Every human has a unique and consistent nasal breathing pattern — so consistent, in fact, that it’s possible to identify someone solely by the way they breathe. That’s the finding of a new study published Thursday in Current Biology, which tracked 100 participants — some for as long as two years — to explore how breathing is unique to each individual. It also showed how breathing patterns can reveal information about a person’s physical and mental health, from body mass index to levels of anxiety or depression.

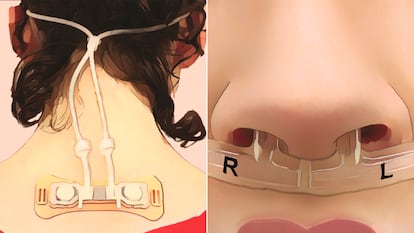

To measure it, the researchers developed a portable device that recorded airflow through each nostril continuously for 24 hours. They then collected data on each volunteer’s physical activity levels and responses to psychological questionnaires. By cross-referencing all this data using artificial intelligence and statistical analysis, they were able to identify 97% of the participants solely based on their nasal airflow patterns. In other words, breathing is as distinctive to a person as their voice or fingerprints, and most of its unique features remain unchanged over time.

The respiratory fingerprint isn’t a fleeting trait and holds enormous potential for science to better understand the mystery of brain function in mammals. Noam Sobel, a researcher at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and co-author of the study, says that “one would think that breathing had already been measured in every sense.” However, his team has discovered a completely new way to analyze it. “We consider it a brain indicator,” he explains.

This is so because, as the researchers have demonstrated, breathing — so unnoticed, even though we do it on average between 12 and 20 times per minute — reflects physiological states and mental traits. Sobel sums it up: “Our levels of anxiety and depression are shaped by our brain, and so is our long-term breathing pattern. So, by reading these patterns, we are, in a way, reading the mind through breathing.”

Although none of the study participants had a clinical diagnosis of any mental disorder, those who scored higher on the psychological assessment tools used to measure severity showed similar breathing patterns. In other words, individual psychological traits can be predicted with statistically significant accuracy based on how the people analyzed breathe.

Now, the million-dollar question seems to be whether our breathing changes because we have anxiety or depression, or if we have anxiety and depression because our breathing changes. “In short, we don’t have an answer. While both are possible options, the latter alternative is, of course, much more exciting because it opens avenues for intervention,” the author notes.

Sobel adds that they are currently repeating the same trials with clinically diagnosed populations to gather more data. “Intuitively, we assume that the degree of depression or anxiety we experience alters our breathing, but it could be the other way around. Perhaps our breathing pattern causes these disorders. If this is true, we could modify breathing to change these conditions,” says Sobel.

Timna Soroka, another researcher at the Weizmann Institute who co-authored the article, points out that one of the most interesting findings of the study relates to sleep. “The waking mind and the sleeping mind are very different, and, in fact, breathing during waking and sleeping is also very different,” she explains.

For example, nasal breathing during sleep is very asymmetrical: most people switch between breathing primarily through one nostril or the other. They also found that participants who scored relatively high on anxiety questionnaires had shorter inhalations and greater variability in the pauses between breaths during sleep. “We don’t yet know what the implications of this are,” Soroka adds.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.