Nazareth Castellanos: ‘Our mind is wandering almost half the time’

We tend to think of the brain as immutable. But the Spanish neuroscientist, who studies its interaction with the heart, gut and other organs, explains its many surprising abilities

Nazareth Castellanos, 45, has a bachelor’s degree in Theoretical Physics and a PhD in Neuroscience from the Autonomous University of Madrid’s School of Medicine. She has trained and worked in prestigious classrooms and laboratories in Germany, England and Spain. But one day, years ago, she realized that while she was rapidly gaining technical-scientific knowledge, she had stagnated completely in learning about herself. That disturbed her, and she vowed to make a change. While she has continued to conduct research – she is currently directing the project Brain-Body Interaction during Meditation at Madrid’s Complutense University – she resolved that, in addition to asking what and how, she would also examine the wherefore and why of her interests. As she asked herself those questions in her own meditation practice, Castellanos began to offer some answers at conferences, colloquia and roundtables. Additionally, she wrote several books about the brain’s relationship with the heart and the body’s other organs, including Alice and the Wonderful Brain, The Brain’s Mirror and, most recently, Neuroscience of the Body: How the Organism Shapes the Brain.

Question. In the 17th century, John Milton said, “The mind is its own place and in itself, can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven.” What determines whether one’s mind is heaven or hell?

Answer. I think it depends on balance…One of the concepts that I like most in cognitive neuroscience is the notion of equilibrium, which is the relationship between mind, matter and body. On the one hand, there are influences and conditions, which pertain more to the scientific field; on the other hand, we have will and effort, things that we do not study from a scientific perspective and that we teach less often in schools. Our will and intention are what distinguish us from other beings. And sometimes they lead us to hell. Although there are also hellish situations you experience but haven’t caused.

Q. There seem to be quite a few hellish situations these days ... is the media being too alarmist?

A. Yes. In my opinion, the media is depicting an excessively dramatic view of things. Everything is horrible, it’s a melodramatic context, everything is uncertain... Be cautious: uncertainty means that you don’t know what will happen, but…the media speaks in a very deterministic way, meaning that everything is and will be catastrophic. It’s kind of like a self-fulfilling prophecy. We are manipulating people a lot and leading them to focus only on how bad we have it.

Q. It’s tempting to think that we’re worse off than ever before.

A. But we have it better than ever.

Q. Well, better than in the Middle Ages, certainly.

A. There’s no need to go back to the Middle Ages! Does anyone believe that during previous pandemics – during the Spanish flu, for example – that the state went and helped teachers get organized, helped companies get aid and ensured that everyone had a minimum level of health care? Well, no, people got by and that’s it. No one says this, and anyone who does say it is accused of being naive and frivolous. I have spent a lot of time studying recovery from brain injury, and I have seen brains in very bad shape whose neuroplasticity has improved a great deal in six months.

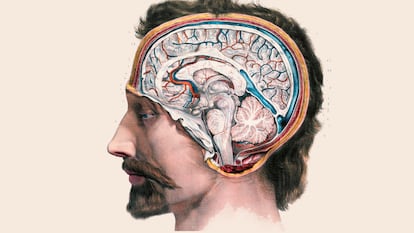

Q. What is neuroplasticity?

A. It is the brain’s ability to reorganize itself. Ramón y Cajal’s great discovery was that our brain is made up of neurons that do not touch. That’s the neuron doctrine. And he discovered the brain’s plasticity. Before that, it was thought that the brain never changed. But it does change, and it evolves.

Q. So, we change a lot more than we think we do.

A. Of course, but we don’t see it.

Q. People don’t seem to like it much when others change.

A. We like people who seem consistent, but of course, consistent, according to our own standards. Don’t let them change my world! Deep down, it’s all about the fear of uncertainty. We are anxious to make everything fit together. That’s where the media and movies and TV shows are very influential. I am studying all of that now.

Q. What specifically are you studying?

A. The influence of everything around us and how susceptible we are to it. I’m currently working on a beautiful project about the interaction between bodies.

Q. What does the interaction between bodies mean?

A. Right now, during this conversation, our bodies are communicating, and not just through words. Our bodies are talking, the brain and the nervous, cardiovascular and endocrine systems are communicating. That is called physiological reciprocity. Let’s say, for example, you’ve come home from work, and you’re extremely stressed out; your cortisol levels are very high. You come home and say, “Okay, I’m going to calm down.” But your body is full of that hormone. And your children’s bodies – because they’re your children – get it, and they start to get a little bit more nervous too. It’s like a virus.

Q. Is it contagious?

A. It certainly is.

Q. That’s incredible.

A. Scientific studies have proven it. For mothers, the reciprocity is the same with sons and daughters. Among fathers, it is more contagious for daughters... We are sponges. And your heart and brain act in a way that reaches your children. If you’re feeling good and your oxytocin levels are high, so are theirs. Of course, it’s not just our children. At work, we can impact others. If my office mate is in a bad mood, that can affect me. We live in an environment, and we must bear that in mind, although sometimes the medical field really isolates us.

Q. For laypeople, the idea that brains and hearts interact sounds like science fiction…

A. Well, that’s how it is. Imagine that a picture of our brains was taken a half-hour ago and another is taken again now, after we have been talking for half an hour. Our brains look increasingly alike. They copy each other. Otherwise, we couldn’t communicate. Communicating is incorporating the other person. I could show you incredible images. It’s called interbrain phase synchronization.

Q. Are the communication and incorporation completely involuntary?

A. Everything is a delicate balance between voluntary and involuntary. The philosopher Henri Bergson defined life as freedom inserting itself into necessity. Take meditation, for example: it’s a dance between the voluntary and the involuntary. You are there, you want to meditate, but you remember that you have to turn on the washing machine!

Q. They say that the most important thing about meditating is to not have expectations and not expect results. Is that so?

A. It’s true. Expectations are a big obstacle to meditating… and …the most frequent reason why people give up. I once attended a 12-day meditation retreat in Nepal. Before we started, they asked, “Who here expects to learn something?” Some people raised their hands. “Well, you can have a refund and go.”

Q. You talk about “mental wandering,” as opposed to “focusing on something concrete,” like scientific research. Can you explain that?

A. It’s one of the most interesting concepts around brain activity. [Writer and priest] Pablo d’Ors said that you have to go from being a wanderer to being a pilgrim. Those two states exist in the brain. According to a Harvard University study, our mind is wandering almost half the time – about 47% of our waking hours. Sometimes – for example, when we do research or when we practice meditation – it wanders. And it’s clear that the mind needs to wander, to get lost... but 47% is excessive! Harvard University found that it is a major source of life dissatisfaction: the mind wandering makes us feel adrift. They wrote about it in a 2010 article called “A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind,” which was published in the journal Science.

Q. But from a neurological perspective, what exactly does wandering mean?

A. It is a state known as the brain’s default mode network [DMN]. The person who discovered it in 1990, Marcus Raichle at the University of Washington, defines it as “the universe’s background noise.” In this spontaneous state, the brain begins to generate activity…randomly. These are called “daydreams.” You may be asked, “What are you thinking about?” and you answer, “Nothing,” because you are not aware of it. But a huge maelstrom is going on in there. Now, of all the functions that this “wandering” serves, it has been estimated that only 30% is necessary. The rest has been proven to be useless…an enormous waste of energy…This has implications for neurodegenerative diseases: the more time you spend in that state throughout your life, the more likely you are to have deposits of beta-amyloid plaques, which is what people with Alzheimer’s and dementia have.

Q. Does all that mental wandering and waste of energy cause frustration?

A. Certainly. For example, all that inner dialogue has to do with narcissism, anxiety, a more negative assessment of your surroundings... because, deep down, many of the thoughts that we have are better than reality… then, suddenly the mind crashes and says, “oh my God, this isn’t what I thought, everything is not so cool.”

Q. Why does mental wandering happen? What causes it?

A. It is a spontaneous brain activity; we don’t know what causes it. Well, nowadays we know that one of the sources is the body itself, what happens inside it, inside the gut, among other places. Hence, the importance of diet and physical exercise. My brain won’t be the same today if I have a donut and Coke for breakfast, as compared to if I have some coffee and good bread with olive oil.

Q. In other words, junk food also influences our brains.

A. We already know that the brain regulates the stomach and the gut. If you are nervous, you can have digestive problems. Right. But in our body, the bottom-up axes are more powerful than the top-down axes. We eat something, which the stomach processes for a half hour, and then it starts to go into the gut. All the intestinal microbiota are there, all those microorganisms that not only function to help capture nutrients, but they also inform the brain and organize some of the neurotransmitters, regulate neuronal growth factors, for learning, for example, and determine our mood. There are studies that have shown that, in children, a poor diet is linked to how many tantrums [they have]. It’s the same for adults. So, in short, what we eat affects areas of the brain.

Q. Well, the saying Mens sana in corpore sano (sound mind in a sound body) has been around for a long time...

A. Exactly. If everyday life is already difficult enough, and then we add fuel to the fire with…poor nutrition... or by breathing incorrectly, for example...

Q. We can breathe incorrectly?

A. Yes, we breathe through our mouth, or our exhalation is shorter than our inhalation, which causes stressful situations. If the exhalation is longer, the brain will better control the endocrine response to stress. The exhalation must be at least twice as long as the inhalation. Why? Because when I breathe in, the brain activates, and when I breathe out, it relaxes. But almost no one does it right.

Q. There are so many things that we don’t see, smell or feel that nevertheless happen to us and help explain why we’re having a bad day, aren’t there?

A. Well, yes.... But look, in ancient India 3,000 years ago, they already knew that breathing influences one’s mental state and had pranayama yoga techniques. But there is a lot of Western arrogance in regard to ancient medicines, so it feels as if we have invented everything recently.

Q. Does the scientific world at large see the same connections between the brain and heart and other parts of the body that you and others have pointed out?

A. There are things that science cannot explain 100%, and then philosophical factors come into play. The scientific world is sometimes cold; that coldness seems dangerous to me. That’s not science; it’s a technique, no matter how sophisticated it may be. I have a computer that measures 1,000 times a second what the body does at 7,000 different points. Incredible, but I can’t tell my mother that! ... For me, the true scientist is the one who obtains data and transforms it into knowledge. Sometimes people want deeper explanations, and because science does not want to make pronouncements, it sometimes leaves the door open for quackery.

Q. In your children’s book Alice and the Wonderful Brain, you argued that happiness can be learned. Is that too bold a claim?

A. Of course it can be learned… Happiness is learned when we learn to take care of ourselves. To my mind, it relates to intimacy, a concept that we should develop much more in society. Pascal said that humanity’s major problem is that we don’t know how to be alone with ourselves.

Q. Maybe we’re afraid.

A. Of course. They did a tremendous experiment at Harvard. They put a group of people into a room with white walls, nothing else. They said, “You can stay there for a minute or for an hour; all you have to do is look within, examine your own thoughts.” On average, people only tolerated six minutes. Seventy-two percent described the situation as unpleasant. The experiment concluded that it’s very difficult to be with someone you don’t know.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.