Is it possible to live with half a brain?

Cases in which essential regions of the brain are missing show the organ’s ability to keep functioning despite major injuries

The engineering of human beings would probably not have pleased a perfectionist like Steve Jobs. The inhabitants of the world today demonstrate how life takes advantage of errors and mutations to adapt to new circumstances. There is no one way to be healthy, and humans can thrive in surprising conditions–including, for example, when missing large parts of their brain.

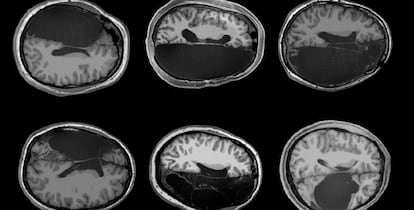

A recent article published in the journal Neuropsychologia describes the case of a woman who discovered during a medical check-up that her left temporal lobe was missing. The region normally plays an important role in the ability to understand language. In theory, this kind of absence should restrict the patient’s linguistic abilities. But she had never experienced those limitations, and she had no idea that anything was missing in her brain.

Cases like this are common. They often have to do with congenital defects that cause strokes in the early stages of development. According to an article in the journal Wired, the sister of the patient analyzed in the Neuropsychologia study is missing her right temporal lobe. But both of the sisters led normal lives, their bodies adapting and reorganizing their brains so that language functions would operate in the intact portions.

Javier de Felipe, a researcher at the Cajal Institute of the CSIC in Madrid, recalls other cases of people surprised by their cerebral peculiarities, such as that of a man who, due to a case of hydrocephalus during childhood, “had water in the brain and the cortex reduced to a small sheet” and yet still led a normal life. He also cites the example of individuals who live practically without a cerebellum. However, he points out, “these alterations occurred in the early stages of life, when the plasticity of the brain makes it possible for other intact regions to replace the damaged functions.” When this type of injury occurs later in life, the result is catastrophic.

The human brain is most flexible in the early stages of its development. At that time, “it is capable of adapting in such a way that, if the visual cortex is affected, a transfer could be carried out so that a part more dedicated to auditory processing compensates for the other lost region,” says Sandra Jurado, a researcher at the Institute of Neurosciences of Alicante (UMH-CSIC). “Once the connections are made, cutting them is traumatic, although there are cases in which there is redundancy in the brain and some connections can be redirected to compensate for part of the lost functionality,” she adds.

Jurado explains that the brain has its own “security systems,” such as cells that repair the minor damage that occurs in day-to-day activities. But like aircraft engineering systems, which have extra parts to prevent a disaster if any of them fails, the brain seems to have redundant parts that can be reused in case of injury, mainly during embryonic development or early childhood. This happens in the parts related to the cerebral cortex, the most distinctively human part of the brain. The more primitive regions, related to basic functions such as breathing or feeling hunger, are more vulnerable, but it is possible to live despite the absence of large regions of the cortex.

“The worms C. elegans all have 302 neurons, but the human brain is much more variable,” says De Felipe. “You can eliminate 4,000 neurons and apparently nothing happens. There is an excess of neurons that we do not know how to explain well, but it can be an evolutionary advantage. It is a capacity that we could perhaps take advantage of if we knew better,” he continues. On the diversity of human brains, the CSIC researcher recalls an astonishing fact: “Lord Byron had a brain that weighed around two kilos, and Anatole France, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature, had a one-kilo brain.”

Cases like the woman with a missing lobe help us understand the location of certain functions and the brain’s ability to reorganize itself. They also raise questions about how the brain really works. An accident can cause an injury that produces vision or hearing damage, but it can also generate what is known as post-traumatic savant syndrome, which causes untrained people to emerge from a mishap with extraordinary mathematical or musical abilities.

De Felipe points out that brain reorganization does not happen only due to errors in genetic programming or accidents. “There is a basic map of the brain, but then the variability from individual to individual is very important, because each human brain is different from another. It depends on your history and all the connections you make when you learn or when you relate to the world.” He recalls a study carried out in Sweden with Portuguese women who worked there as cleaners. Part of the group was literate and the other was not. Analysis of their brains showed that learning to read in childhood conditioned the regions they used as adults to process language.

The mind is a result of our brain matter’s interaction with the rest of the body and the world. But factors such as education or culture can modify that piece of matter, leading to results as surprising as the appearance of animals capable of traveling to the Moon. People who live without a piece of their brain are a radical example of the versatility of the organ that makes us human.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.