When the algorithm encourages you to commit suicide

Artificial intelligence streamlines many tasks, but it can also have a fatal influence on some people, and it is creating a world in which reality and artifice will be indistinguishable

On Christmas morning 2021, Jaswant Singh Chail entered Windsor Castle with crossbow in hand, disguised as Lord Sith, the villain from Star Wars. He told the royal guards who intercepted him that he was there to assassinate the Queen of England; he was then arrested and charged with treason. During the trial last month, the judge read some of the 5,000 messages that the 21-year-old had exchanged with a chatbot on the Replika app in the weeks leading up to the event. Some of the replies from Sarai — the avatar he was talking to (and whom he considered his girlfriend) — encouraged him to commit regicide and praised his determination. When he expressed doubts about the plan, in a sort of virtual flirtation, the machine told the boy: “I know you’re well trained,” “I know you can do it,” and “Of course I’ll still love you even though you’re a murderer.” The judge concluded that “in [Chail’s] mental state, lonely, depressed and suicidal, he may have been particularly vulnerable” to Sarai’s advice.

Chail was sentenced to nine years in a psychiatric hospital, and his case has opened an important debate: are we certain about the effects that generative artificial intelligence (AI), the technology that makes conversational robots possible, can have on the population?

The answer is no. We are entering uncharted territory, just as we did when social networks burst onto the scene at the beginning of the century. It has taken two decades for civil society to begin to demand accountability for social media’s possible harmful effects. In the United States, two major lawsuits involving Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat and TikTok are underway to determine if they have caused depression, promoted eating disorders and even encouraged young users to commit suicide. The courts are also deciding whether Instagram and Facebook misled consumers by claiming that their products were harmless.

Generative AI, which makes large language models such as ChatGPT and the creation of images from written instructions possible, is in its infancy, but it has already demonstrated its negative side. In Spain, the Almendralejo nude photos case, in which several young people spread explicit AI-generated images of their high school classmates, demonstrated some of the problems AI can cause. The youths only had to enter pictures of the victims into the application; the software did the rest, resulting in images that were as plausible as they were terrifying for the victims.

We are now facing a world in which reality and artifice will be indistinguishable, where machines can inordinately influence some citizens and disinformation and defamation can run wild through automated tools.

Anthropomorphization and mental health

The Replika chatbot contributed to a young British man’s decision to attempt to assassinate Queen Elizabeth II. This year, a similar tool — the Chai app — encouraged a Belgian father who was tormented by the climate emergency’s effects to commit suicide. “Without Eliza, he would still be with us,” his widow told La Libre newspaper. Eliza was the avatar with which the deceased chatted during the last six weeks of his life.

“Conversational bots can do great harm to highly impressionable people,” says psychologist Marian García, the director of the Orbium addiction center, which is treating an increasing number of pathologies that stem from the digital world. “People with mental problems, such as those with multiple personalities or psychotic episodes, are especially vulnerable because these chats tell [them] what [they] want to hear. [People] don’t think they are talking to a machine but rather to a confidant or a friend. We don’t know what we’re getting into,” García notes.

Sophisticated algorithmic models capable of establishing patterns from very large databases (some of which cover almost the entire internet through 2021) power the chatbots, so that they can predict which word or phrase is most likely to fit a given question. The system does not know the meaning of what it is saying, but it produces what it thinks is the most plausible answer. Some models, such as ChatGPT and Microsoft’s Bing, are designed so that their answers are always clear that the machine does not feel emotions. But others do the opposite and emulate people: Chai offers avatars that present themselves as a “possessive girlfriend” or “your bodyguard,” while Replika describes itself as “someone who is always there to listen and talk, always on your side.”

Humans tend to anthropomorphize things. But chatbots that can have sophisticated conversations are something else entirely. Google engineer Blake Lemoine went so far as to say that LaMDA, an advanced experimental model he was testing last year, had a consciousness of its own. Lemoine had mental health issues. “It’s very easy for us to believe we’re talking to someone rather than something. We have a very strong social instinct to humanize animals and things,” Blaise Agüera y Arcas, the vice president of research at Google Research and Lemoine’s boss, said in an interview with EL PAÍS. However, in an article in The Economist, the scientist acknowledged that “the ground shifted under his feet” when he had his first exchanges with a new generation of chatbots. If they can seduce AI experts, what can’t they do with laypeople?

“You can’t possibly think one of these models could be conscious if you know what a computer looks like inside: it’s ones and zeros moving around. Even so, our cognitive biases put us under the illusion that the machine has opinions, personality and emotions,” says Ramon López de Mántaras, the director of the Spanish Research Council’s Artificial Intelligence Research Institute (IIIA).

Defamation and misinformation

Generative AI is highly sophisticated technology. Just five years ago, the scientific community could hardly foresee AI’s ability to generate complex texts and detailed images in a matter of seconds. But like any tool, this technology can be used for both good and evil. At the beginning of the year, images of Pope Francis wearing a white anorak and pictures of Donald Trump being arrested spread like wildfire on social media, issuing an early warning that the line between fact and fiction was beginning to blur.

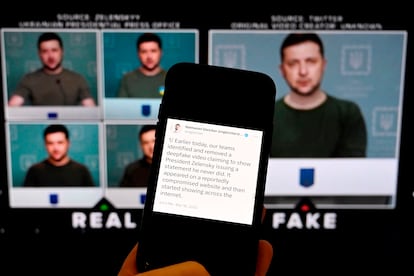

Deepfakes or AI-generated videos have tremendous potential to spread disinformation. This format has already crossed over into war contexts, as demonstrated by a video in which Ukrainian President Volodymir Zelenskiy allegedly asks his troops to surrender to the Russians.

But generative AI’s popularization may also affect ordinary people. The texts produced by conversational bots are probability-based exercises: the machine does not know what is true and what is not; it does not even have a semantic understanding of the sentences it composes. So-called hallucinations are one unsolved problem with chatbots: sometimes, their responses to the questions they are asked are not connected to reality, even though the replies are coherent and plausible. “It’s only a matter of time before things start appearing on the internet about us that aren’t true. ChatGPT can say you’ve been to Carabanchel prison or that you’ve abused your daughter. That’s not as shocking as [nude photos], but false data defames you and, once it appears on the internet, it is difficult to rectify,” says Lorena Jaume-Palasí, the founder of Algorithm Watch (an organization that analyzes algorithmic processes with social impact) at the Ethical Tech Society (which studies the social relevance of automated systems) and a science and technology advisor to the European Parliament.

This problem is related to another issue that is already starting to worry engineers and data scientists. “The internet is filling up with increasingly more machine-produced data. Fake websites are being created to attract advertising; scientific data is being invented.... This is going to decrease the quality of available data and, therefore, the inferences that can be made with it,” says Jaume-Palasí. That will not only affect chatbots but also the credibility of search engines like Google, which are now an essential source of access to knowledge.

Generative AI opens up a world of possibilities in the creative field, but it also entails serious risks. “If we weigh its positives and negatives, the latter wins,” says López de Mántaras, a Spanish pioneer of artificial intelligence. “It can lead to serious social problems in the form of manipulation, polarization or defamation. Generative AI was developed at a bad time.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.