The discovery of Camilo Torres’ body revives one of the most sensitive issues in Colombia’s internal conflict

The remains of the religious leader, who was killed in his first battle as an ELN guerrilla, were missing for 60 years. During this period of time, his memory and legacy have been invoked either to justify the armed struggle in the country, or to criticize it

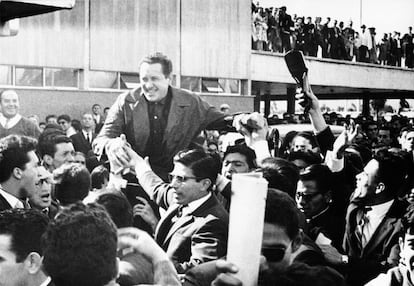

One of the biggest and longest-standing questions surrounding the internal conflict in Colombia has begun to find its answer. On Friday, January 23 — just over three weeks before the 60th anniversary of the death in combat of Camilo Torres Restrepo, a priest and guerilla — a group of forensic experts confirmed the discovery and identification of his remains. These had been missing since the moment of his death in San Vicente de Chucurí, in the department of Santander, on February 15, 1966.

As a result of this discovery, the story of one of the most symbolic figures of the Latin American armed struggle is beginning to come to a close.

Before becoming a symbol of the armed struggle, Camilo Torres was a priest. In the early-1960s, he was deeply involved in the intellectual and social life of Bogotá’s elite. He baptized Rodrigo García Barcha, the eldest son of Gabriel García Márquez and Mercedes Barcha, when the writer was still a young journalist who belonged to the university cliques of the capital. Torres was also chosen by Hernando Santos Castillo — then-director of the Colombian newspaper El Tiempo — and his wife, Helena Calderón, to baptize their son Francisco “Pacho” Santos. Within that same family setting, he officiated other sacraments: former Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos served as his altar boy at the age of 12.

The memory of Camilo Torres has always been present in the discourse of the National Liberation Army (ELN). In fact, in 1987, the guerrilla group changed its name to the Camilista Union-National Liberation Army. And, on several occasions, the armed group’s peace negotiators have conditioned any sitdowns with the Colombian government on the discovery of the remains of the man they consider to be their greatest ideological figure.

The ELN’s appropriation of Torres’s legacy is quite debatable. On January 23, Walter Joe Broderick — the priest’s biographer — said on Caracol Radio: “Those four or five old men from the ELN keep up that ‘peace’ story because that’s how they make a living… but they’re no longer an army, nor a liberation army, nor a national army.”

President Gustavo Petro has made a similar criticism. Amid his insistence on achieving peace with the ELN, he has repeatedly invoked the figure of the priest as an example for the current guerrilla leaders. He accuses them of having strayed from the legacy of the priest they themselves have turned into a legend.

Camilo Torres is one of the most representative historical figures of the Colombian internal conflict. Born into an aristocratic Bogotá family, he entered a seminary in his youth. His religious path drew inspiration from both the reforms being promoted by the Second Vatican Council within the Catholic Church, as well as the 1959 triumph of the Cuban Revolution led by Fidel Castro. This led him to embrace a leftist ideology that fought for social justice.

After studying Sociology at the University of Leuven in Belgium, he returned to Colombia and became a prominent figure in national public life. He underwent a process of radicalization, becoming convinced that armed struggle was the only way to achieve social change. Thus, in 1965, he joined the ELN. Torres was then killed in his first battle, on February 15, 1966.

The priest’s turning point as a political actor occurred in the early-1960s, at the National University of Colombia. After returning from Belgium, he was appointed university chaplain and became a prominent figure in debates on poverty, inequality and social reform. In 1959, along with Orlando Fals Borda, he co-founded the Faculty of Sociology at the National University, considered the first of its kind in Latin America. The project received support from American institutions, such as the Rockefeller Foundation, amidst strong international interest in studying the social transformations in the region following the triumph of the Cuban Revolution.

Before resorting to armed struggle, he promoted forms of community organization as part of his commitment to grassroots social transformation. He was one of the driving forces behind community action boards, which were conceived as spaces for neighborhood participation to address specific problems related to services, infrastructure and local organization in working-class neighborhoods and rural areas. In his book about Torres, the writer Walt Broderick explains that the priest “saw community action as an opportunity for students to project themselves beyond the walls of the city and its academic ‘ivory towers.’”

This social work had its roots in his earlier labors in the low-income neighborhoods of southern Bogotá, particularly in Tunjuelito, where Torres supported community initiatives and maintained daily contact with poor and working-class families. There, he practiced a priesthood outside the confines of churches: he visited homes, participated in neighborhood meetings and supported community initiatives. This experience — more than any academic study — shaped his decision to break the boundaries of traditional pastoral work. It also reinforced his conviction that poverty isn’t an individual moral problem.

From the National University, he also spearheaded the creation of the United People’s Front in 1964. This political platform sought to unite students, workers, peasants and other sectors around a minimalistic program of social transformations, independent of the traditional political parties.

The United Front convened massive public rallies and voiced its criticism of the National Front: an agreement between the elites of the Liberal and Conservative parties, which averted an undeclared civil war between their members in exchange for sharing power from 1958 until 1974.

In 1965, the guerrilla priest wrote his Message to the United Front, a text that sought to define the platform’s direction. “This is one of the greatest responsibilities of the non-aligned; [we] must always strive to unify and not seek or allow new causes of conflict. We must not forget for a single moment that our work is oriented toward adding to, not subtracting from, efforts,” the proclamation reads. “We are friends of ALL revolutionaries, wherever they come from.”

The growth of the United Front and Torres’s increased public visibility strained his relationship with the Catholic Church. In early-1965, the hierarchy ordered him to withdraw from political activity and cease his public appearances, deeming them incompatible with his religious duties. And this wasn’t an isolated incident: it was part of a broader dispute between conservative sectors of the Colombian Church and priests who, inspired by the Second Vatican Council, promoted closer ties with the poor and a social interpretation of the Gospel. The sanction ultimately isolated him institutionally and closed one of the avenues through which he had attempted to promote reforms.

The Cuban Revolution was a central reference point in his political radicalization. Like much of the Latin American left in the early-1960s, Torres closely followed the island’s political process and interpreted it as proof that structural transformation was possible in societies marked by inequality and exclusion. His understanding of Cuba’s downfall fueled his conviction that gradual reforms were insufficient and that, in certain contexts, armed struggle acquired an ethical justification.

Beyond the symbolic appropriation of his image by the ELN and some leftist groups, the decision to keep Camilo Torres’s remains on the National University campus aims to link his memory with his academic and public career, prior to his time with the guerrillas. The Search Unit for Missing Persons (UBPD) — a state entity created by the Peace Agreement with the FARC — will coordinate the handover of the remains to his family and close associates in a ceremony that (for now) will be private.

Colombia’s most important public university — which has adopted the image of Che Guevara as a symbol of the student movement — will now build a mausoleum in Camilo Torres’s memory. One of the longest chapters of the Colombian internal conflict has begun to draw to a close.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.