Pope Francis’ new show of support for liberation theologists

The pontiff has reinstated Miguel D'Escoto, a suspended Sandinista priest and minister

Pope Francis has not been on friendly terms with liberation theology and its priests, who are often labeled as Communists. Yet the pontiff is making unequivocal gestures indicating that he wants to rehabilitate – or at least free them – from past condemnation and excommunications. It’s obvious that he lived alongside liberation theologists in his native Argentina where he was the leader of the Jesuits. His own congregation was a breeding ground for that school of thought. Some priests under his leadership suffered brutal persecution as the dictatorship kidnapped, tortured and even killed sympathizers.

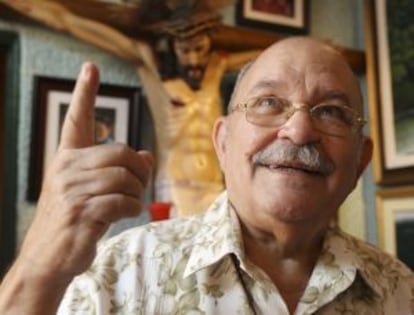

Vatican Radio announced the news of Miguel D’Escoto’s reinstatement on Monday. This is a gesture of understanding or, at least, of mercy toward those chastised theologians. The pope has reinstated the 81-year-old priest and former Sandinista minister of foreign affairs, whom John Paul II suspended a divinis in 1984. D’Escoto may now return to his ministry, give holy communion and take confessions from the faithful.

The former minister – a member of Maryknoll Lay Missioners – wrote a letter to Pope Francis in the spring, asking to be allowed to give communion again “before dying.” The Argentinean pontiff did not wait long before answering. He lifted the priest’s “suspension a divinis” and, according to the Spanish news agency EFE, he asked Maryknoll to reinstate D’Escoto as soon as possible.

Miguel D’Escoto Brockmann was born on February 5, 1933 in Los Angeles. He was ordained in New York in 1961 and soon became an advocate of liberation theology. His collaboration with the Sandinista movement began in 1975 through the Solidarity Committee in the United States. After the Sandinistas won power, the Junta of National Reconstruction named him foreign minister. D’Escoto held his post throughout Daniel Ortega’s first controversial presidential term. When Ortega returned to power in 2007, the former priest was named border and foreign affairs advisor. He is now retired.

Will there be more rehabilitations of liberation theologians or of priests who entered politics against the Vatican’s wishes and orders? Probably. This gesture sets a precedent in a church that rarely rectifies its own actions and when it does so it is only after many centuries have passed, hence the saying: “Roma locuta est, causa finita est” (“Rome has spoken; the case is closed”).

The pope said: “Get your affairs in order with the Church.” The photo of the scolding was seen around the world

John Paul II of Poland and his faith “police officer,” – then cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, now emeritus Benedict XVI – issued a severe condemnation of liberation theology. They ousted teachers and thousands of priests around the world, including in Spain. The most notable cases happened in Nicaragua, especially when the government – after toppling a brutal United States-backed dictatorship – entered an undeclared war with the superpower and its President Ronald Reagan, who was bent on pushing Sandinistas out of office.

John Paul II made things worse, especially during his trip to Managua on March 14, 1983. Despite being called anti-clerical and Communist, the entire executive staff went to the airport to welcome the pontiff. There were two priests in Ortega’s cabinet: D’Escoto and Minister of Culture Ernesto Cardenal. His brother, Fernando Cardenal, a Jesuit priest, was in charge of the Sandinista literacy campaign. After giving a welcome speech, President Ortega introduced the pope to his Cabinet members. John Paul II wanted to greet them one by one. When he reached Ernesto, the trappist monk and minister took off his beret and knelt. And the pope said: “Get your affairs in order with the Church.” The photograph of that scolding was seen around the world.

But Ernesto Cardenal, a well-known poet at the time, did not mind the pope’s reprimand. Neither did his congregation. A little later, his brother Fernando became minister of education. He did not fare as well as Ernesto. The Company of Jesus bowed under Vatican pressure (it even threatened to suspend the order) and told him he could no longer be a Jesuit if he continued to work in politics. “I may have made a mistake by becoming a Jesuit and a minister but let me make a mistake in favor of the poor because the Church has made many centuries’ worth of mistakes in favor of the rich,” Fernando told his superiors.

Juan José Tamayo, a liberation theology lecturer who has also been reprimanded by the Vatican, says “bishops, theologians, priests and religious people have always participated in politics in Latin America, since the beginning of colonization until today. And not only on behalf of the colonizers. It was often on behalf of marginalized priests.” Some of the most emblematic cases include those of Bishop Bartolomé de Las Casas and Dominican friar Antonio Montesinos.

In the 1970s, theologians and priests reaffirmed a political commitment rooted in a revolutionary Christianity, for which Camilo Torres became a symbol almost as mythical as Che Guevara. In 2008, Fernando Lugo, a former bishop, became president of Paraguay in on the Patriotic Alliance for Change ticket. He defeated the Colorado Party, which had been in power for 60 years. “From now on, my cathedral will be my entire country. Until now, I had been in a cathedral – teaching, sharing, suffering, building.”

Lugo had worked as a teacher before serving as a missionary in one of the poorest areas in Ecuador. Then he studied sociology in Rome. The Vatican named him Bishop of the Diocese of San Pedro. When he left the bishopric, the Church suspended him a divinis even thought at first it had given him its blessing to leave and turn to politics. Benedict XVI lifted the punishment on Lugo in June 2008. The former priest was once again a regular parishioner who could receive all Catholic sacraments. And, the Church granted that if Lugo – who had made a scandalous exit out of politics – asked to be reinstated, “the Holy See would study” his case.

Haiti’s Salesian priest turned president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, advocated liberation theology. He actively participated in toppling the Duvalier regime while serving as parish priest in a poor Port-au-Prince neighborhood. In December 1990, he was elected president with 67 percent of the vote. His top priorities were the eradication of poverty and assistance to the poor he had served. But a military coup soon ran him out office. Though he was later reinstated as president, Aristide slowly changed his lifestyle and distanced himself from his earlier commitments.

Translation: Dyane Jean François

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.