Gabriel García Márquez’s archive in Austin reveals all the secrets about his unpublished novel

‘Until August’ — Gabo’s posthumous book — will hit bookstores on March 12. Underlying this novella by the Colombian Nobel Prize winner are doubts about his desire to publish it, as well as the reasons why his heirs made the decision to do so. EL PAÍS visited the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, where five drafts of the short novel — with his handwritten corrections — are treasured, along with the rest of the Nobel Prize winner’s legacy

The final chapter of Gabriel García Márquez’s literary body of work was always there, in boxes labelled #1 and #2 in the writer’s archive his family sold in 2014 to the Harry Ransom Center, a brutalist fort on the campus of the University of Texas in Austin.

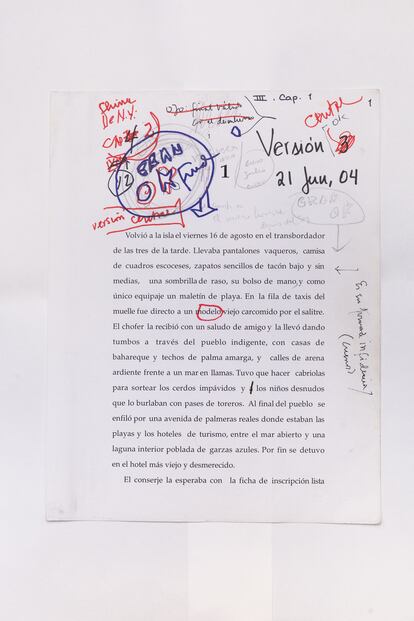

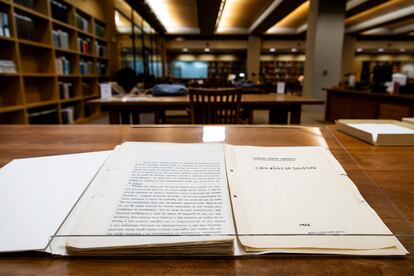

Distributed in yellow folders, there are five hand-corrected drafts of the novella En agosto nos vemos — translated from Spanish as Until August — dated between June and July of 2004, along with two “drawer” copies and another titled From Los Angeles, referring to the city where the author worked on the piece while receiving cancer treatment, and several fragments that he sent to his literary agent in Barcelona — Carmen Balcells —. That was years before 2010 or perhaps 2011, when García Márquez, who falled into the abyss of dementia in his last decade, said: “This book is useless. “We have to destroy it.”

But Until August wasn’t destroyed. It will be released in Spanish on March 6, the day the writer would have turned 97-years-old. The launch — simultaneous in 40 languages, including in English on March 12 — promises to be the global publishing event of the year. The heirs — Rodrigo García and Gonzalo García Barcha, children of the Colombian Nobel laureate and Mercedes Barcha, who died at the beginning of the pandemic — reviewed the novel a couple of years ago and decided that it deserved to be published.

“That was his last effort against his fading memory,” Rodrigo, the first-born son and a renowned Hollywood filmmaker, explained to EL PAÍS a couple of weeks ago, via video call from Mexico City. “He worked intensely on [the novella]. And then — as he forgot things — he forgot the book, too. My theory is that when he said it didn’t work, he had lost the ability to judge it. It’s not as polished as his other novels, but it’s not an incomprehensible mess, either. I just think he no longer understood anything.”

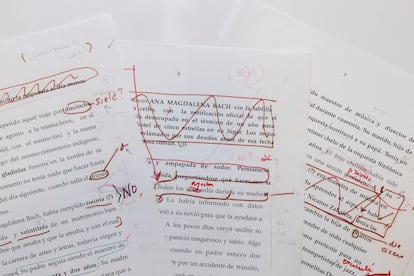

García Márquez died in April of 2014, almost 10 years ago. To put his materials in order, his sons turned to the Spanish editor Cristóbal Pera, who worked with the writer on his autobiography, Living to Tell the Tale (2002). Pera — who is now VP publisher of the Planeta publishing house in the United States — used his free time to sit in the attic of his house in New Jersey and look through all of the novelist’s corrections, made in his devilish handwriting with red ink. “I didn’t have to add anything — that doesn’t even need to be said. I just had to try to understand which version was closest to the final product. I had to do the job of an editor, as if I were next to him, following his notes,” he clarifies.

To the greatest extent possible, the children wanted to respect the state which the story was left in when their father gave it up. Rodrigo García says that they even refused to fix “a couple of contradictions” in the text, after some of the translators pointed them out.

The plot of the 110-page novella remains just as its author left it. The protagonist is a middle-aged woman named Anna Magdalena Bach (like the composer’s second wife), no-doubt a nod from the music-loving Gabo (his nickname). His readers will know that, for him, names were an important matter. “The characters in my novels don’t walk on their own feet until they have a name that identifies with their way of being,” he wrote in his memoirs.

Anna Magdalena Bach’s way of being is that of someone who embarks on a journey of sexual exploration outside her marriage. And every year, on August 16, she visits the island where her mother’s tomb is, to plant gladioli and update her about what’s been going on in her life (in a twist typical of Gabo’s universe, his widow — Mercedes Barcha — died a day earlier: on August 15, 2020). It’s not exactly clear when or where the story takes place, but it’s a contemporary tale, which is interesting when compared to the rest of the writer’s work, most of which is set in the 19th and early-20th centuries.

When his sons sold his archive to the University of Texas at Austin — consisting of 80 document boxes, 15 oversize boxes, three oversize folders and 67 computer disks — the heirs restricted access to Until August, because they were still deciding what to do with the text. During the 2017 digitization process of 27,000 documents, the typescript wasn’t included. In the Harry Ransom Center, Jim Kuhn — the man responsible for the operation — explains to EL PAÍS that “just over half” of the materials were put up online. Several photographs and letters were excluded. Much of this material remains with the novelist’s family, while various public figures who corresponded with García Márquez — from Woody Allen and Bill Clinton, to Fidel Castro and Akira Kurosawa — either retain their copyright over what they wrote, or their heirs do.

“It was an act of generosity… a very good way to share the writer’s legacy and creative process,” Kuhn affirms. “It’s not so common for the families of authors of that magnitude to allow it, because it’s often believed — I would say erroneously — that it negatively impacts the sale of books.” For instance, anyone who wants to read, say, Love in the Time of Cholera can do so for free by consulting the manuscript online. But Rodrigo García downplays the importance of the family’s gesture. “After all, if you put the title of any novel in Google, you get a PDF; it’s incredible,” he laments.

Digitization hasn’t diminished the interest in consulting the Colombian Nobel laureate’s documents in-person, either. Kuhn notes that the García Márquez Collection — a window to Latin America in an institution that houses the archives of James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, J. M. Coetzee and David Foster Wallace — is among the most requested by researchers who come to the center’s monastic reading room.

When researchers were eventually allowed to consult the unpublished novel, the Colombian writer and journalist Gustavo Arango — who read it in Texas — published an article singing its praises. Pera says that this was another reason that moved the family to finally publish it (although some excerpts have already seen the light of day, since someone photographed them in the reading room and circulated the pictures online). “Obviously, [the family] hasn’t published it now for the money,” the editor adds. “Gabo’s work is very much alive… in China alone, 10 million copies of One Hundred Years of Solitude have been sold in recent years.”

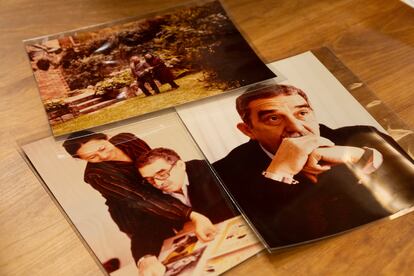

In the archive, there’s also a trace of the public life of Until August. There are photos of a 1999 event at Casa de América — organized in Madrid by the General Society of Authors — in which you can see the writer reading a version of the first chapter. He appears alongside another winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature: the Portuguese José Saramago. EL PAÍS journalist Rosa Mora — who was at that event — wrote a chronicle in which she explained the plot and said that it was the first of the “five [independent] stories” that would make up the Colombian’s next book. “They seem like absolutely closed, standalone stories… but they form a united whole,” her article reads.

In a telephone conversation from Barcelona, Mora recalls that “there were great expectations, because word spread that Gabo was going to read something new. We were all very aware of him at that time, but we must keep in mind that he wasn’t an author who published every two or three years. He liked to announce things and give clues [about projects] that didn’t materialize until some time later.” The following Sunday, EL PAÍS published a revised version of that text. And, in one of the boxes of letters to his literary agency, there’s also a trace of when the novelist decided to give this newspaper (along with the Colombian magazine Cambio) other materials related to the unpublished novel. A version of the text that he read aloud in 1999 was subsequently published as a short story in 2003, titled The Night of the Eclipse.

In all these publications — including when the Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia published the first chapter again, just a few days after the author’s death — it was highlighted that Until August would complete the trilogy “about love in middle age.” The first two instalments had been Of Love and Other Demons (1994) and Memories of My Melancholy Whores (2004).

“That’s also why we wanted to publish it,” Rodrigo García says. “I think it closes this triptych very well, on a feminist note. Narrated from a woman’s point of view, it seemed to us that it was going to expand Gabo’s world for his readers… and, above all, for his female readers.”

The different versions kept in Austin are written in Palatino font, the type used on the first Apple computers, which Gabo embraced with enthusiasm (the last computer he owned is also in the Harry Ransom Center). “He only used them to write and read the [online] newspapers, nothing more. He was a perfectionist and liked to [clean up the page] before he finished. With the typewriter, he wasted a lot of time correcting errors,” Rodrigo García remembers. “With the computer, he went from one page a day to four or five.”

After printing those pages, the author pointed out reiterations in red or in pencil, eliminated phrases such as “the black clouds filled her with a dark omen,” or changed his mind about the age of the protagonist. A careful study of those erasures and marginal notes allows us to peek into the mind of the writer, just before he got lost in its labyrinth.

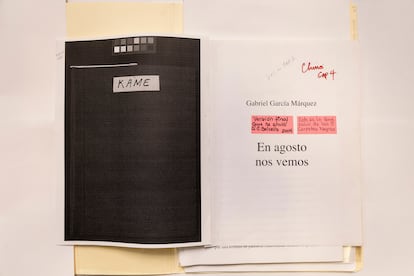

These markups helped Pera interpret the author’s intentions. The editor based the published posthumous novel on the fifth version, which was kept inside a black Leuchtturm folder, a brand that García Márquez favored. On this fifth version, the author scrawled the words “Big Ok.” Pera also compared this text to a “[Word document] kept by his secretary, Mónica Alonso.”

In reality, Pera’s work on the novel began long before Gabo’s children called him two years ago. “One day, in 2010, [Carmen] Balcells told me in Barcelona: ‘Cristóbal, you have to get Gabo to finish the novel he has in his hands,’” he recalls. “When I returned to Mexico, I told him. He was amused [and] clarified that it was indeed finished. To prove it, he read me the last paragraph. Then, for months, he didn’t let me see it anymore, until, one day, he allowed me to read three chapters aloud to him. It was very exciting.”

In the reconstruction process, Pera also had the help of Alonso, who was his faithful secretary during the last years of his life, when the writer — who had always considered himself, as his biographer Gerald Martin recalls, a “memory professional” — began to lose his bearings. Alonso is very discreet about all of this: she declined to participate in this article.

This painful process was recorded by Rodrigo García in the moving memoir, Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes (2021). This is an account of his grief and his final goodbyes to his parents. In the short book, he narrates the difficult years of his father’s struggle with dementia. At one point, he describes how García Márquez forgot who his beloved wife was: “Why is she here giving orders and running the house if she is nothing to me?” This infuriated Mercedes, who was calmed down by her son: “It’s not him, Mom. It’s the dementia.” In the end, this proved to be a one-time event: she regained a proper place in his mind, even as he lost track of everyone else.

“Something that set him apart from other writers was his continuous editing process. He was always improving his texts, which reveals his journalist’s nature,” explains Álvaro Santana Acuña, a professor of Sociology at Whitman College, in the state of Washington. “Due to his health problems, in the case of Until August, he had to stop halfway. Five versions may seem like a lot, but we must remember that 18 drafts of Memories of My Melancholy Whores are preserved [in Austin]. With his early books, there’s usually only one draft available, because — until he was 45-years-old — he was a globe-trotting writer who changed countries every so often. He didn’t carry files or libraries with him.”

Santana Acuña is one of the people who best knows the papers in Austin. His study of the archive helped him write the book Ascent to Glory (2020), a kind of biography of One Hundred Years of Solitude and its enormous and unexpected success. In fact, because of his intimate knowledge of the documents, the Harry Ransom Center even asked him to curate an exhibition — Gabriel García Márquez: The Making of a Global Writer — in which the scholar was able to put Gabo in the context of other great authors, teachers and friends from the 20th century, including James Joyce, William Faulkner, Jorge Luis Borges, or Julio Cortázar, whose papers are also kept in Texas. The exhibition has so far been held in Austin and Mexico City. It’s scheduled to travel to Colombia next year.

That idea was part of the institution’s efforts to disseminate Gabo’s legacy, according to Stephen Enniss, the center’s director. In an interview in his office — before the gaze of T. S. Eliot, portrayed on canvas, as well as a bronze bust of the Irish poet Derek Mahon, whom the director wrote a biography about — Enniss recalls that completing the acquisition of García Márquez’s papers was the first big project he took on when he arrived at the Harry Ransom Center a decade ago.

“One day, I got a call from a dealer in New York named Glenn Horowitz, who asked if we would be interested. We were lucky to be the first ones he asked, because I think anyone would have jumped at the chance to raise the money,” he smiles. At the time, Enniss didn’t want to disclose how much was paid for the collection, but an access-to-information request filed by the Associated Press with the Texas Attorney General’s Office revealed the amount to be $2.2 million. However, 10 years later, Enniss continues to maintain secrecy: “Saying how much you give to the heirs [of an author] for their files is inflationary. Because another family will come along who, obviously, believes that their parent is worth just as much as Gabo in terms of literary value and they’ll want the same, or even more.”

The decision to send the Nobel laureate’s treasures to the United States — rather than leaving them in Colombia, where he was born, or in Mexico, his home for decades — was widely-criticized. Perhaps for this reason, the Harry Ransom Center worked to catalog and make the archive available to the public as soon as possible. In 2015 — just one year after Gabo’s death — it opened the collection up for public consultation. And, two years later, digitization arrived. “We also keep the archive alive, we continue to buy [more documents] whenever there’s an opportunity,” emphasizes Megan Barnard, the deputy director, who explains that there’s a box that was added in 2022 with papers found in the family home, following the death of Mercedes Barcha.

The latest item to arrive following the initial acquisition at auction is a letter from around 1950, addressed by García Márquez to his friend Carlos Alemán. In the letter, he’s already discussing the central character in One Hundred Years of Solitude, 17 years before the novel’s publication.

That the archive is extraordinarily accessible is proven by the fact that it only takes 20 minutes for anyone who arrives at the university with an ID to be able to get their hands on the typescript of One Hundred Years of Solitude and read legendary first sentence: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

Santana Acuña regretfully compares the fate of Gabo’s legacy with that of his literary agent’s papers. “The Spanish government bought them [in 2010, after Balcells’ death in 2015]... and so many years later, they’re still in boxes, they’re not even accessible to researchers, we’re not even talking about their digitization,” he laments. It’s certainly a shame. If one looks at her letters to her star writer, which are preserved in Austin, one will discover a prose writer who — although she was relentless when it came to business — was also affectionate with those she represented. In one postcard, she writes: “I send you a big hug and we’ll see what the hell we can give you for your birthday.”

The Balcells Agency — with the zeal of its founder — continues to represent the legacy of García Márquez. They’re preparing for the next milestone in 2027 — the centenary of the author’s birth — and the premiere of the first eight episodes of the Netflix version of One Hundred Years of Solitude, scheduled for the end of 2024. The serialization of the novel is something that the author didn’t want, although his sons ultimately decided otherwise.

“The objection he had is that he preferred [the novel] not to exist visually, but only in the imagination of the readers,” Rodrigo García admits. “But, oftentimes — since he was also a lover of film and television — he also said, ‘man, it wouldn’t be bad if it could be done in maybe 100 hours.’ What he didn’t want was for it to be a two [or four-hour-long] movie with Hollywood actors. And he had no prejudice against television: he liked a good series.”

Rodrigo García adds that the family came to the conclusion that “sooner or later, it was going to be done. If not by our children, by the grandchildren… and if not by then, [it would hit the screen] when the novel ends up in the public domain. We saw that Netflix had an interest — they were going to spend good money on the production, they weren’t going to have the flimsy budget of a soap opera — and they were also going to listen to all of our demands. So, it seemed like the right time.”

Some of the conditions were that the series be filmed in Colombia, in Spanish, with a Latin American team. “There will surely be a lot of debate about this. People will say that Gabo didn’t want it. But hey, there’s something that will always free us from guilt, which is what he always used to tell us: ‘When I’m dead, do whatever you want.’”

It will be thanks to that phrase — a phrase that sounds like it came from one of the characters in his novels — that his readers will be able to return to the little town of Macondo with the upcoming series. And they’ll also be able to remember Gabo next week with the release of Until August, the chapter that closes his literary body of work.

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.