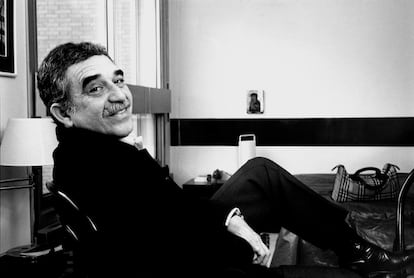

An unpublished interview with Gabriel García Márquez: ‘Maybe the myths about me are more interesting than my life’

In collaboration with documentary filmmaker Jon Intxaustegi, EL PAÍS offers excerpts from a 1994 interview with the Colombian Nobel Prize winner in which he discusses music, the Caribbean, money, love, books and ideas

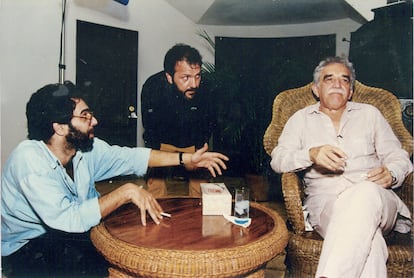

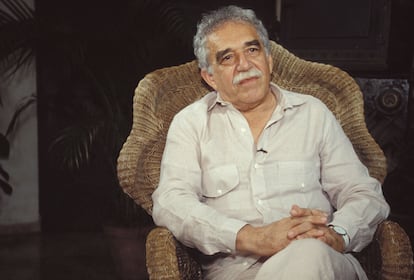

The excerpts that follow are part of an extensive conversation with Gabriel García Márquez, which I recorded on May 6, 1994, in Havana, Cuba, with the participation of the recently-deceased journalist Mauricio Vicent. The Colombian novelist was 67 years old at the time, and he spoke openly, revealing his full, overwhelming self. His novel Of Love and Other Demons had just been published.

In the interview – unpublished until now, and the full version of which is available inside Issue 117 of the cultural magazine TintaLibre – the winner of the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature discusses music, the Caribbean, money, love, his books and his ideas.

Gabriel García Márquez: Perhaps they’ve taken it as a bad joke, or a good joke… but I believe that One Hundred Years of Solitude is a 450-page-long vallenato (a Colombian folk song). And I say this with absolute seriousness. The esthetics are the same, the concept is the same, the resources are the same: stories that are out there and that are lost, lost in popular oblivion. Love in the Time of Cholera is a 380-page-long bolero (a Cuban romantic song) and I say this with all seriousness. When no one knew what vallenato songs were, I remember that, as a child, I went to listen to the accordion players, who arrived during the festivals, because that’s the origin of vallenato music… they were traveling musicians who went from town to town, singing about an event that had occurred somewhere else. They were traveling newspapers that were accompanied by accordions.

At first, what interested me most was the story they told, not so much the music. But, afterwards, for me, the history, the facts — and practically the life of the region — always remained linked to music. I have the impression that of all my books, the one that best summarizes the Caribbean is Of Love and Other Demons. In Love in the Time of Cholera, the city [that portrayed] the Caribbean authenticity isn’t as accentuated [as in] Of Love and Other Demons. In fact, if in any book of mine you can see how we Caribbean people truly are – a mixture of many races from which a new culture has emerged – it’s in this book.

Question. Even though Of Love and Other Demons is set in Cartagena, Colombia, I see it as very Cuban, with experiences and ways of life that still exist.

Answer. Nowhere does the book say that the city is Cartagena — and that’s not purely coincidental. I’m interested in the uncertainty, I just wanted to make clear that the book takes place in any city in the Caribbean. I had never dealt with the African ingredient of Caribbean culture as closely as in this book. In Cartagena – due to the special conditions of the colonial period and the very special conditions of Spanish colonialism – these cultures didn’t catch on, or weren’t as well-preserved as they were in Cuba. All the information that’s [in the novel] couldn’t have been obtained just from Cartagena… and probably in no other single city in the Caribbean.

It’s an issue that I bring up and that no one wants to pay attention to, but the Caribbean isn’t a geographical area, but rather a cultural one. It doesn’t only cover the Caribbean Sea. For me, it begins in the south of the United States – everything that is Louisiana and Florida – and extends to northern Brazil. That is, it’s not a geographical territory, but a cultural territory.

I’ve taken elements of African culture incorporated into the Caribbean from both Brazil and Cuba and it all works as if it were in Cartagena. I was born in Aracataca — which is a Colombian town inland, but not very inland, it’s still pure Caribbean — and that’s a region not only of Colombia, but of the entire Caribbean, whose culture is fundamentally determined by music.

Probably the most Caribbean city of all is Panama. Where one really feels the Caribbean is in Panama; I feel it ecologically, I feel it in the sense that my body begins to feel [at ease] in the ecological environment of the Caribbean. This happens very easily to me when I come back from Europe, on my first stopover in the Caribbean. I get down [from the plane], I breathe and I’m already a different person. I believe that this is something that hasn’t been studied enough: to what extent the ecological conditioning of human beings is fundamental in their lives.

Q. Is it true that, with the first pesos you earned, you went on a cruise to the Caribbean?

A. What would be great is to collect all the myths that exist about me, because maybe they’re more interesting than my life!

Q. Could it be that you yourself encourage these myths?

A. Well let’s see: when I was writing The Autumn of the Patriarch, in Barcelona, there was suddenly a moment when I realized that I had left my ecological environment behind. There were things that I no longer felt: I had forgotten the color of the sea, the smells. I found that I didn’t remember specific things, things that I needed to express that reality. The emotion, the feelings, the awareness of where I was from was never lacking, because wherever the writer is, he carries his world; the poet carries his world and wherever they place him — at the North Pole or the South Pole — he carries it within. But I couldn’t remember what certain things were like: the smells, the sounds, the temperature. It’s very difficult to imagine heat when it’s cold, and vice versa.

I got very worried, because the novel was blocked. So, I took a break and went on a tour that took me to Santo Domingo. And, from Santo Domingo, I went down the entire arc of the Caribbean to Cartagena and recovered everything I needed, all the fuel I needed to write the book. I didn’t take a single note: it was simply a matter of living, of going about it, visiting all the islands of the Caribbean, one by one, without doing absolutely anything other than simply seeing. And I didn’t need to spend a year doing it: it was three days here, or a week there. When I returned, the book came flowing to the end. I had simply gotten back into the sauce. But that’s different from forgetting… [because] you really never stop being where you are from.

Q. And during your nights in Barcelona, what boleros did you listen to?

A. I listened to some boleros that weren’t from the Caribbean at all: it was Bach, of equally popular origin. At the end of the day, all music – cultured music and popular music – have the same origin in popular songs. There’s a photo in the immense iconography of [the Hungarian composer] Béla Bartok which is terribly moving: he appears with one of those cylinder recorders, collecting stories from the peasants of Transylvania, from the land of Dracula. Almost all of his music has that popular origin – as did Bach’s, as do vallenatos, as does almost all Caribbean literature. Music, for me, isn’t only classical music or only popular music… only [after listening to a lot of it] do I start to distinguish the genres I like the most and the genres I like the least. But you cannot say that classical music isn’t music, or that popular music isn’t music, or that the bolero is not, but the cha-cha is. I believe that they’re all human expressions of great value, because even the least legitimate ones have something to them. I can’t really write while listening to music, because, at some point, I’m more interested in what’s playing than what I’m writing.

Music touches me more than literature, or it must be that I like it more, or that music imposes itself on me more than literature. I don’t listen to it while I write, but I’m always immersed in it, particularly when I’m writing. When I was in Barcelona — during a hiatus after One Hundred Years of Solitude looking for a path, to see where I would go next — I listened to a lot of music. I had always listened to music — cultured music, above all — but not in an organized way. I just heard it as it came, wherever it came from. In Barcelona [in the 1960s], the advantage was that one could listen to music everywhere, it’s an eminently musical city. I was especially listening to Béla Bartok’s third piano concerto – which I really like — and I played it a lot precisely in the days when I was writing The Autumn of the Patriarch.

When it was published, there were some experts — in both literature and music — who tried to show me that, somehow, the composition, the structure of that book, was based on that Béla Bartok concert… although I could never understand the explanation they gave me. One has to wonder what genre of music Of Love and Other Demons is! I have no idea, but it’s likely that it also has its own music. What I wanted was for [the novel] to be music without a single discordance. For that to happen, you need to work on a 200-page book for four years, every day, making sure there isn’t a single discordant note.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.