All the horror of Pinochet’s dictatorship fits on a mother-of-pearl button

The memory of state repression has divided Chilean society ahead of the presidential runoff on Sunday, in which the far-right candidate, José Antonio Kast, is the favorite

Massive human rights violations occurred during the Chilean military dictatorship. And the memory of these atrocities fits on a tiny mother-of-pearl button. Villa Grimaldi was one of the most symbolic torture and extermination centers of Augusto Pinochet’s regime (1973-1990). Since 1997, it’s been a museum. There, visitors can see a railway track that’s been preserved: the bodies of victims of state terrorism were tied to it, before they were thrown into the sea.

Of the hundreds of corpses dropped into the Pacific, only one surfaced, in September of 1976: that of Marta Lidia Ugarte Román, who was murdered at the age of 42. However, another piece of evidence exists: a small button, almost fused with the iron, rusted after years at sea. This discovery is the focus of Patricio Guzmán’s powerful documentary, The Pearl Button (2015). It’s the last memento of a human being who was disappeared by the dictatorship, and it’s proof of the long period of repression, during which at least 3,200 Chileans were murdered.

Contemplating it in one of the rooms of Villa Grimaldi, enlarged by a magnifying glass, opens the door to the abyss that represented the years of death under Pinochet. On a peaceful morning in late November, in the middle of the southern spring, two groups visit this former torture center located in Santiago de Chile, at the foot of the Andes Mountains. When it closed, the perpetrators tried to erase the evidence of what had happened there, but with the advent of democracy, it was converted into a memorial center, one of many scattered throughout the Chilean capital. Visitors can see Londres, 38—which gives its name to British lawyer and writer Philippe Sands’ book about Pinochet’s arrest in London and the fight against impunity— the National Stadium—where the U.S. citizen Charles Horman was murdered, whose case is recounted in Costa-Gavras’ film Missing—the Palacio de la Moneda itself, and the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, which recalls what happened after the coup d’état against the government of Salvador Allende on September 11, 1973, and puts a face to a significant number of those who were murdered. Throughout Chile, 1,168 places of memory are preserved.

In 1978, the dictatorship enacted an amnesty law, to cover the first five bloodiest years of the regime. And, after the return to democracy in 1990, successive center-left governments established two truth commissions. Ultimately, due to the fact that crimes against humanity are not subject to statutes of limitation, a significant number of perpetrators have been tried. Some still remain in prison.

At Villa Grimaldi, 4,500 political prisoners were detained, including a very young Michelle Bachelet — who governed Chile twice, from 2006 until 2010 and 2014 until 2018 — and her mother, Ángela Jeria. Bachelet’s father, an Air Force general who opposed the military coup, had already died from torture inflicted by his own companions. A total of 239 of the prisoners were ultimately disappeared and executed.

After being converted into a memorial site, a wooden tower where many detainees were subjected to prolonged torture sessions was reconstructed. There, too, is a panel displaying the faces of the murderers, among them Miguel Krassnoff. Born in Austria in 1946 and trained at the School of the Americas in the former Panama Canal Zone, he was an official with the sinister National Intelligence Directorate (DINA), Pinochet’s political police, and the perpetrator of countless atrocities. He was sentenced to more than 1,000 years in prison for crimes against humanity. Today, he’s still incarcerated at Punta Peuco Prison, in the Santiago Metropolitan Region.

According to all the polls, the far-right candidate José Antonio Kast – who leads Chile’s Republican Party – is predicted to win the second round of the presidential elections on Sunday, December 14, over the left-wing candidate Jeannette Jara. During the 2017 presidential campaign, Kast claimed that he didn’t believe everything that was being said about Krassnoff, a murderer who symbolizes all the brutality of the Pinochet regime. In his current campaign, he hasn’t ruled out pardoning him, as proposed by the failed presidential candidate Johannes Kaiser of the libertarian right.

However, in the final stretch of the campaign, Kast has attempted to soften his rhetoric. “Today, there’s a bill being debated in Parliament… and it’s [offering amnesty] for humanitarian reasons. I don’t believe in plea bargaining; I believe in justice. And this means treating people with terminal illnesses, or those who are [no longer conscious], with respect,” he declared on December 1, 2025.

Now, as the election date approaches and as Kast’s victory seems highly probable, those responsible for these memorial sites fear that there will be an attempt to erase the living memory of the ruthless repression that followed the 1973 military coup. Besides insecurity — the issue that has dominated the campaign above all others, with clear xenophobic undertones and promises of mass deportations of migrants — the way in which the past should be addressed is one of the issues that most divides Chilean society today.

The left defends the preservation of memorial sites as a kind of “never again” etched in stone, as well as the continued pursuit of justice. Right-wing politicians, however, believe that what they consider to be old wounds have already healed, or they’ve outright defended the legacy of the dictatorship.

Throughout the 2025 campaign, Kast has remained silent on this matter, but back in 2017, when he was running for president for the first time, he defended the Pinochet regime. “You don’t have to be very creative to think that, if he were alive, he would vote for me,” he shrugged.

“It’s obvious that we’re worried about what might happen after the elections. The museum is part of what [the right] considers to be a ‘culture war,’” explains María Fernanda García Iribarren, director of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights. The cultural center and archive operates as an independent foundation, receiving direct state funding through federal budget allocations. “It’s an emblematic place, not only in Chile, but worldwide. Consensus about the past is built [here]. And it’s very important that these spaces undergo constant reinterpretation,” this cultural manager emphasizes. She was part of the international committee of experts that advised the regional government of Navarre, Spain, on the reinterpretation of the Monument to the Fallen in Pamplona. This is one of the most significant traces of Francoism in Spain.

On its website, Villa Grimaldi offers a Declaration Against Denialism, in which the institution also expresses its concern for the future of the institution — and the future of historical memory — should Kast win: “The [rhetoric of] right-wing candidates represents a real threat that jeopardizes progress achieved by families, institutions and human rights actors over decades… [their speeches are] provocations that border on inhumanity.”

“One of the museum’s objectives is that we don’t repeat what happened [and] that we don’t treat each other as enemies again. Denialism is a danger to democracy,” García Iribarren adds. The museum that she directs — a project promoted by Michelle Bachelet during her first presidency and inaugurated in 2010 — not only speaks about the past, but also about the present: it currently houses an exhibition on the children kidnapped by Russian forces in Ukraine. It recently offered another one on the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II.

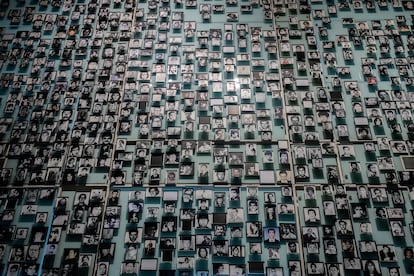

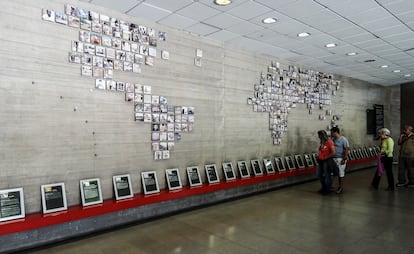

Before entering the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, one can contemplate a work by the Chilean sculptor Alfredo Jaar. Through darkness and disorientation — followed by an infinite play of mirrors — it forces the visitor to reflect on what it means to glimpse one of the most painful memories of the 20th century. In the museum’s main hall, an immense panel displays the photos of many Chileans who were disappeared and murdered. Visitors can click on the faces of the victims on a table in front of them: a biography then appears. They can also light up a virtual candle. The aim is to try to restore humanity to those who were swallowed up by repression.

At Villa Grimaldi, evidence of the crimes committed at the site has been erased. All of it is gone: the tiny cells in which prisoners were crammed together, the torture chambers, the barracks where the military and police officers who ran that concentration camp lived. A majestic ombú tree survives; it’s an immense tree, native to South America. “It’s a tree of memory,” a guide explains, while speaking to a group of visitors one morning. But it was also part of the torture system, because some prisoners were hung from it as a way to terrorize the others. There are no photographs of Villa Grimaldi from the years when it was operational. There are only drawings by survivors, as well as their testimonies. What does remain, however, is the gate through which the vehicles carrying the detainees entered. It was closed with a chain when the museum was inaugurated, as a powerful symbol that this gateway to hell will never be opened again. Not there, nor anywhere else in Chile. Some 3,200 people were murdered during the 17 years of the dictatorship, of whom 1,469 were victims of enforced disappearance. To this day, the remains of 1,092 victims have not yet been found.

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.