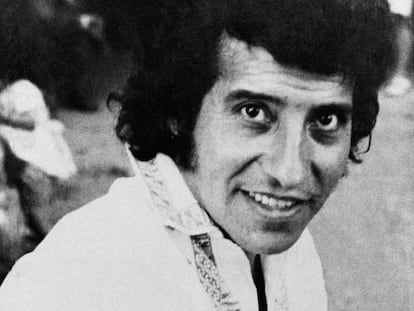

The last days of Víctor Jara: Chile’s political poet killed by the Pinochet dictatorship

A new biography about the singer-songwriter recounts the months and days before he was executed after the 1973 coup against Salvador Allende

In August, 1973 – a month before he was tortured and assassinated by Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship – the Chilean singer-songwriter and theater director Víctor Jara experienced moments of heartbreak. His story exemplified the convulsive period in the lead-up to the coup on September 11.

Perhaps knowing what was coming, he wrote some verses that, today, seem oddly prophetic. He even sent his wife – Joan Turner, an English dancer – and their daughters, Manuela and Amanda, to take refuge in a house in Isla Negra, a town located about 60 miles from the capital of Santiago. This, he said, was “in the event that a coup d’état led to a civil war,” says a new biography on Jara by Mario Amorós, a Spanish writer. It is titled La vida es eterna (Life is eternal), after one of Jara’s verses from his song, Te recuerdo, Amanda (I remember you, Amanda).

Jara was arrested one day after the coup, the 50th anniversary of which will be commemorated in September of this year. He had gone to the State Technical University (UTE), where he worked, after receiving a call from the socialist president Salvador Allende. He was subsequently taken by soldiers to Chile’s National Stadium, where he was tortured and executed, alongside Littré Quiroga, director of the National Prison Service.

The communist singer-songwriter received at least 23 bullet wounds. His corpse was thrown onto a public road, where he was recognized by passers-by who notified his family. Eight former soldiers have been convicted of the crime.

For his book on the singer of classic Latin American songs, such as El derecho de vivir en paz (The right to live in peace), Amorós reviewed hundreds of files and interviews that Jara gave in different parts of the world. He studied his discography – which marked a milestone for Chilean songs and Latin American music – and reviewed the more than 11,000 pages of the legal file on Jara’s case. He also collected testimony by friends and family of the singer, who discussed the days spent at Isla Negra, the same seaside resort where the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda lived.

One of the testimonies cited in the book is by the artist’s daughter Amanda Jara, who recalled those times. She remembered, for example, when she was a child in 1973, she witnessed the discomfort felt by her mother and father when they saw “some Navy ships making movements.” Despite the tension, “they didn’t say anything.”

“One afternoon, she and her father went for a walk along the rocky beach of the place that captivated Neruda. As they walked, he began to invent the lyrics and music for a song and asked his daughter for advice. That composition by Isla Negra was lost… but he was able to record another, Manifesto, which was born from the depths to express, in a definitive way, the reasons why he took up the guitar,” reads the biography.

This intimate scene was detailed by his wife, Joan Jara, in a book she wrote about her husband: “He was calm while working on the song; introverted and self-absorbed. I would hear him hum softly in the studio while I worked at home. At times, he would appear and ask me to listen to him. Although the song was beautiful, my heart sank when I heard it.”

Manifesto was recorded in August of 1973. Here is a verse that is translated from the Spanish original: For a song has meaning/when it beats in the veins/of a man who will die singing,/truthfully singing his songs.

On September 4, 1973 – just a week before his assassination – Jara participated in the last rally of the Popular Unity (UP) political party, along with hundreds of supporters of President Allende.

“They carried a banner that proclaimed: ‘Workers of the cultural sector against fascism.’ He was well aware of the serious political situation… he was afraid of what could happen to him, as he expressed in a premonitory way in letters and in some of his songs, and to his family,” says Amorós.

At the end of the 1960s, Jara left behind a successful theater career to sing political and protest songs in support of the UP. In 1973, three years after Allende was elected president, he returned to his origins: folklore. But he did it in his own way.

“His last record was Canto por travesura (I sing for mischief), released in September of 1973. It’s a compilation of peasant songs. Surely, many people must have been surprised that, [after his political songs], he returned to the purest folklore. However, he pointed out that this was simply one more example of his [political] commitment, because he went even deeper into the popular soul by publicizing compositions created by the workers themselves,” recounts his biographer.

“In what were the last months of his life, his musical creation reached its highest level of commitment to poetry and beauty. Thus, in May of 1973, he wrote Cuando voy al trabajo (When I go to work), inspired by the construction worker, José Ricardo Ahumada. But, unlike his combative tribute to Miguel Ángel Aguilera in 1970, which ends with three [repetitions of] ‘we will triumph,’ this song concludes with a chorus of verses shrouded in uncertainty: ‘Working on the beginning of a story / without knowing the end…’”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.