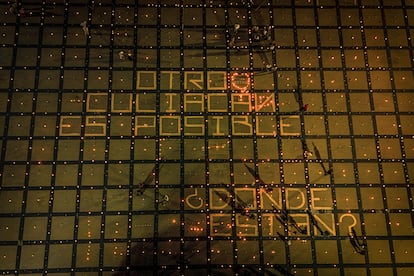

Searching for missing persons amid the Sinaloa Cartel war

The crossfire between Los Chapitos and the faction loyal to ‘El Mayo’ Zambada has generated a spike in disappearances in the last year with a dominant pattern: male, up to 40 years old, and from Culiacán

— Go, it’ll be better for you.

— Why are you letting us go?

— Because, in the end, my mom is going to go with you to ask them to come and look for me.

This was a brief conversation between a hitman and Mrs. Reynalda Pulido, a woman who has located more than 40 bodies and remains in Sinaloa over the past year, trying to find her son Javier Ernesto Vélez Pulido, who disappeared on December 8, 2020, a case that is now being targeted by the Culiacán Municipal Police.

“The difference is that now the hitmen see us and they better step aside. It’s like they know this is the end for them,” Pulido says, as if trying to describe how the war in Sinaloa, fought between Iván and Alfredo Guzmán, sons of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, and Ismael Zambada Sicairos, son of Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, could end.

It was April 2, and she was headed toward El Pozo, a desolate town after the cartel used explosive-carrying drones, dropping their loads directly on random houses while residents ran to hide in the woods or other buildings. She was told she’d find at least 20 bodies there, some even in graves. She found nothing but the hitman, playing Charon on the edge of the town that had become the vestiges portraying the conflict.

“If you’re looking for bodies, you’d better leave now, because the ones they left behind were left to me. They told me to bury them, and I can’t tell you where, because if not, I’ll be next,” the man told Reynalda.

— At least let me take some pictures.

El Pozo is an arid town that makes its living with livestock and some crops, fed by the nearby Tamazula River. Because of this waterway, in recent years it has been filled with laboratories for producing methamphetamine. This drug requires tributaries to cool the containers and, incidentally, to provide a dumping ground for leftover chemicals.

The people there became spectators and, little by little, victims, surrounded by armed men, some recruited to produce the drug, and many others buried after dying of poisoning or murder.

In El Pozo, only burned houses remained. Others had their facades destroyed by bullets, with corral fences open to let the cattle out so they wouldn’t die of hunger, or with bombs buried in the ground because they failed to detonate when dropped from the air.

Reynalda left El Pozo and was unable to return, but she says she owes a debt to the more than 200 families who have joined her collective, Mothers in Struggle, during the cartel’s internal war. They are all victims of the same conflict.

“All the bodies were recent”

Marisela was told that Alejandro could be at one of the ranches north of Mazatlán. She is searching for her son, Ismael Alejandro Martínez Carrizales, who disappeared on July 12, 2020, when armed men pulled him from his car and, in front of his girlfriend, disappeared him.

The woman received the information anonymously, via text messages and coordinates, but after three days of searching through weeds and trash, she couldn’t find a single clue that led her to her son.

“I’m not sure he’s among those we found, because they were all recent,” says Marisela as she recounts the bodies and remains she’s been able to find in the past year: “There are 50 people, some in Miravalle, others in Villa Verde, they’ve been in various places, but of all of them, only three have been identified because they say they don’t have a geneticist who can perform the comparisons.”

The last year, she says, has been spent going back and forth to abandoned places, enduring the heat and the silence of the authorities regarding the large number of missing young men.

“They are laborers, and we wanted the authorities to take us to the mountains, towards Durango. They told us that there are camps there where they torture boys, kill others, and make some work. This information matches the photos they have shown us and comments made by investigative police officers, but they do nothing, they just laugh and play with the victims,” says the woman.

The shadow of recruitment: men under 40

According to data from the Sinaloa Attorney General’s Office, there is an alarming pattern: the majority of disappearances over the last year involve young men, mainly between the ages of 18 and 39, with a high concentration in Culiacán and an unprecedented spike beginning in September 2024.

The records reviewed show that 84% of the victims are men, while women represent only 15%. Cases of trans women were also documented, although in a minimal proportion — only two.

Age confirms the vulnerability of youth: 44% of those missing are between 18 and 29 years old, while 28% are between 30 and 39 years old. Overall, nearly three out of four disappearances affect people aged under 40. Adolescents account for 13% of cases, while adults over 50 account for no more than 11%.

On the state map, Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa, accounts for 19% of the cases, followed by Mazatlán (6%), and Ahome (4%). Other localities with significant cases are the city of Navolato (3%), Villa Juárez (2%), and Eldorado (2%). The distribution shows that disappearances are concentrated in the main urban centers and their surrounding areas. At least those are the ones for which there are reports.

The analysis reveals a worrying trend, as since September 2024, one in six cases recorded during the period have accumulated, with 12% of the historical total occurring in a single month. In October, the figure remained almost as high. In contrast, last July and August barely reached around 3% each.

The data reveal an important pattern: being male, young, and living in Culiacán increases the risk of disappearing in Sinaloa.

Shot and dumped in a septic tank

Ramiro (a fictitious name for his safety) was an employee of a cable company. He and three colleagues were returning from Mazatlán, but decided to take Highway 15, the toll-free route from south to north. However, they were intercepted by a group of armed men near Tacuichamona, a town south of Culiacán.

They interrogated them, asking if they belonged to “La Chapiza,” the faction of the Sinaloa Cartel led by the sons of El Chapo, but they all denied it. The hitmen didn’t believe them. They were forcibly stripped, and their clothes were burned in front of them. Then they shot each of them once. Ramiro was hit in the neck, but survived. He collapsed unconscious.

Their bodies were dragged to a septic tank south of Tacuichamona. They were thrown into the water, some of them with stones tied to their feet.

Ramiro remembered that when he fell into the water, he could feel himself cushioned by another body, a woman’s, or so he thought, because she had long hair. He spent hours there — he doesn’t know exactly how long, but enough to leave him almost in the darkness. He opened the hatch and managed to get out, soaked and covered in shit, with blood still oozing from his body.

He made his way through the woods until he met a man who sheltered him and took him to Culiacán to be treated.

“The next day his brother brought him to me because he wanted to tell me that his friends were there, to ask me to go and get them, because they didn’t deserve to be there,” says María Isabel Cruz Bernal, founder of the Warrior Scenthounds collective, who has been searching for Reyes Yosimar García Cruz since January 26, 2017, when a group of armed men took him from his home in the Infonavit Humaya neighborhood.

“But we couldn’t just go. That’s what I’m telling you happened a few months ago, and as soon as we went, we were met with horror.”

María Isabel and her group, which brings together more than 800 families with missing relatives, successfully persuaded the Navy to carry out a special operation to escort her and 15 other women.

They got out of the truck and, as soon as they opened the first septic tank, they found a body. Then another hatch and a skull. They went to another pit and from there they pulled out hair. Another pit and more bones. They opened a final pit and there they found another corpse. The smell was a combination of raw sewage and death.

“And we have to go back, bring in excavators, because I’m sure there are more bodies. Some had stones tied to them and they may still be at the bottom,” says the mother who is searching for her child.

Ramiro left Culiacán, fleeing with a scar on his neck, the trauma and pain of having been the one who survived to tell the tale.

A forensic crisis that began in another war

The State Search Commission announced in May that it would begin a major effort: to remove the remains of people buried in the 21 de Marzo cemetery in Culiacán. The remains of 830 unidentified people lie there, some from the last cartel war, which ran from 2006 to 2014, and others from more recent years, but the site is already overcrowded; there’s no room for more bodies.

The state agency spent two weeks working at the cemetery but was able to remove only 11 bodies. During that time, the search for the current cases was suspended, but the collectives decided to ignore them and continue searching.

The bodies lying in the 21st of March cemetery are the story of a forensic crisis that began with the previous war, in which prosecutors allowed bodies to pile up in morgues and mass graves without identifying them. There were too many, say forensic doctors interviewed, so much so that they had to ask funeral homes for help in analyzing the bodies in their cold rooms.

The story of that war is similar to this one. Overworked forensic doctors and experts are putting together albums of very crude photographs to show to those who come to the Forensic Medical Service looking for missing relatives, trying to find out if they were found dead.

During this period of war, more than 200 people have been located but remain unidentified. The searching mothers are told there is no geneticist available, but that team is busy working on past cases.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.