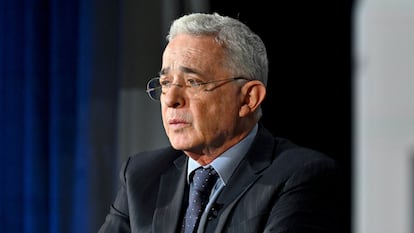

Colombia’s ex-president Álvaro Uribe sentenced to 12 years of house arrest

Judge Sandra Heredia wants the sentence to be applied immediately in what has become the most significant court case in recent Colombian history. But his defense said they will appeal

Former Colombian President Álvaro Uribe Vélez was sentenced on Friday to 12 years of house arrest, a sentence that the judge wants enforced immediately. The decision was made by Judge Sandra Heredia, who on Monday convicted the former president in the most significant court case in Colombia’s recent history. The sentence, which was leaked shortly before the public reading convened by the judge, may be appealed by Uribe’s defense team.

The lower-court judge has had the enormous responsibility this week of handing down a ruling against the former conservative president, who was in power from 2002 to 2010 and helped propel two more presidents into office in 2010 and 2018. The case has had the country glued to their screens, following lengthy public hearings for over a year, as if it were the best series on Netflix.

On Monday, Heredia delivered a verdict finding Uribe guilty of two counts of procedural fraud and three counts of bribery of witnesses in criminal proceedings. Simply put, Uribe attempted to evade justice in various ways, in 2017 and 2018, when his emissaries offered benefits to former paramilitaries to testify in his favor in court.

This is not the final word. Because this is a lower-court ruling, the former president’s defense team has already announced it will appeal, and the case now moves to the Bogotá Superior Court, which must rule before mid-October to avoid the statute of limitations. Legal experts consulted by EL PAÍS believe that, although time is short, they have no doubt the court will give this case priority, given that this is one of the most sensitive cases in Colombian politics.

If the Bogotá Superior Court upholds Heredia’s ruling, the defense team still has the possibility of going all the way to the Supreme Court of Justice, where, curiously, this story began. The former president had filed a complaint there against left-wing congressman Iván Cepeda, accusing him of having ties to paramilitary groups and of bribing witnesses to sway them against himself. In 2018, the Supreme Court closed the case against Cepeda and opened one against Uribe, alleging that he was the one who sought to bribe witnesses.

The false witness case could have been investigated there, avoiding several years of judicial entanglements, but Uribe, anticipating that he would fare better in the ordinary courts, resigned his immunity as a senator, and the investigation was handed over to a Prosecutor’s Office headed by an ally of his, Francisco Barbosa. A tortuous path began, with the Prosecutor’s Office requesting that the investigation be closed, but judges on two occasions requested that it proceed to trial. Prosecutor Barbosa completed his term, the new Prosecutor Luz Adriana Camargo, nominated by the leftist president Gustavo Petro, appointed a new prosecutor, and the trial ultimately fell into the hands of Heredia.

Some of the senators closest to former President Uribe have been denouncing lawfare (the weaponization of justice for political ends). Vicky Dávila, an independent right-wing candidate, asserted that it is “the materialization of criminal revenge against those who confronted terrorism,” alluding to Uribe’s aggressive campaign against leftist armed groups during his tenure.

These claims are not just an isolated strategy of Uribe’s supporters. The U.S. government, which has already imposed tariffs on Brazil for its trial against former President Jair Bolsonaro, has echoed the lawfare argument. Besides Secretary Rubio, several Republican congressmembers have lashed out at the South American country. Senator Bernie Moreno asserted that “Colombia gets one step closer to illegitimacy. We’ve seen this movie before in Venezuela.”

Uribe’s star has faded as Colombia has changed course. When he was in power he was an enormously popular president who connected with people thanks to a tough security policy against armed groups like FARC. Some saw him (and still see him) as a war hero. His influence allowed him to handpick the next two presidents: Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018) and Iván Duque (2018-2022). However, he felt betrayed by Santos— his former minister of defense — who signed a peace agreement with the FARC. And, when it came to Duque, Uribe ultimately distanced himself from his former political ally when he came to the conclusion that he didn’t have the necessary strength of character to govern effectively.

With additional reporting by Lucas Reynoso and Juan Diego Quesada.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.