Salvatore Mancuso, the Colombian paramilitary who did not want to remain silent

The United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia commander was one of the most feared warlords in the country and has accused heavyweights in the political and business world of having allied themselves with the paramilitary armies

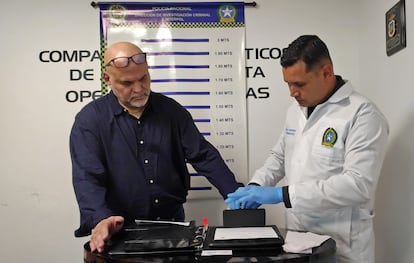

A few days before Salvatore Mancuso landed in Colombia after 15 years in a U.S. prison, the Colombian defense minister told the press that he was arriving at a delicate moment. “Salvatore Mancuso’s life must be protected,” he warned. The life of any Colombian must be protected by the state; the minister appeared to be stating the obvious. But Mancuso’s life could be particularly at risk.

Mancuso, who for now will be held in Bogotá's La Picota prison, was a warlord and still holds many secrets surrounding the armed conflict in Colombia. Previously a well-to-do cattle rancher, he went on to lead paramilitary armies alongside the founders of the so-called United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), the brothers Fidel and Carlos Castaño. With them, Mancuso forged military, political, and business alliances with the most powerful men in the country. And he was a cruel man: he ordered massacres, homicides, disappearances, kidnappings, and displacements. He has been accused of more than 60,000 criminal acts, combining those he committed directly and those for which he is responsible by chain of command. The Castaños died before the paramilitary demobilization, without facing justice or confessing to their crimes. Mancuso, however, is still alive. And, since he demobilized in 2004, he has been a confessional: he has admitted to hundreds of crimes and has accused politicians, businessmen, and the military of having helped him. He is a man many want to remain silent. He is also a man many others want to listen to.

“I come to continue with my commitments to the victims, as I have done uninterruptedly throughout these last 18 years, but at the same time, I come to put myself at the service of a peace agenda that will prevent Colombia from being an eternal factory of victims and collective pain,” Mancuso said in a letter published upon landing. “I have the task of continuing to provide truth before the transitional justice system, not only with responsibility for the implications it has on the people linked in the testimonies, their families, and the victim communities. I will do so under strict standards that allow corroboration to determine that it is a qualified truth,” he adds.

“Stop telling the leftists of the JEP [Special Jurisdiction for Peace] things you should not tell,” read a threat Mancuso received in 2021. The JEP is the transitional justice tribunal agreed between the government and the now defunct FARC that currently investigates the major crimes committed by the former guerrillas and the security forces. The court admitted the former paramilitary chief to its jurisdiction in a controversial move, on the grounds that he has much to contribute to clarifying the crimes committed by the military. Mancuso has, he said in disclosing these threats, an “unwavering commitment to the truth.”

Mancuso came to paramilitarism in the 1990s through the Convivir, the initially legal cattle ranchers’ associations that sought to protect themselves from guerrilla extortion and attacks. Many of these groups ended up financing and strengthening the extreme right-wing paramilitary groups that already existed in some areas and spread and strengthened thanks to this new support (and money from illicit businesses, spearheaded by drug trafficking). “The Convivir was the way in which illegality was given legality,” Mancuso told the JEP. Today, the ranchers are trying to revive an organization similar to the Convivir. Mancuso’s arrival is a stark reminder of that violent past.

In Mancuso’s mouth, the truth is often explosive: he has said that army commanders asked the paramilitaries to assassinate social leaders, that some soldiers accompanied him on kidnappings, and that the security forces did not try to stop several massacres of which they were previously informed. He has also provided names: he singled out as allies of the paramilitaries the sub-director of state intelligence, José Miguel Narváez, for giving lists of people to assassinate; the former vice-president of Colombia, Francisco Santos, for requesting the formation of a paramilitary bloc in the capital; and emblematic companies of the Colombian economy such as Postobón, Ecopetrol, and Bavaria, for aiding the paramilitaries. Most of those accused have proclaimed their innocence, although others, such as Narváez, have been convicted in court.

But it is Álvaro Uribe — Colombia’s president from 2002 to 2010, who decided to extradite Mancuso to the United States in 2008 — who has faced the most explosive accusations. For critics of the then-popular right-wing leader, the decision was an attempt to silence the former commander; for Uribe and his supporters, it was a necessary sanction for a dozen paramilitary leaders who continued to commit crimes from prison. Mancuso has said that Uribe’s closest advisor during his time as governor of Antioquia in the 1990s, Pedro Juan Moreno, helped shape and strengthen the paramilitaries, and that he was an intermediary for Uribe in ordering a massacre (in the town of El Aro) and a murder (of human rights defender Jesús María Valle). He has also said that Uribe removed the security detail of El Roble Mayor Eudaldo Díaz, knowing that the paramilitaries were going to assassinate him.

The former paramilitary chief has admitted that the AUC sympathized with Uribe’s ideological approaches, and claimed that they supported the former president’s election in 2002. “I received orders directly from my commanders to support President Uribe, who was running for president at the time,” he said of that election. The former president has categorically rejected all accusations in the media, on social networks, and in the courts.

In 2004, when Mancuso demobilized, he visited Congress. He gave a speech in which he affirmed that the paramilitaries had made an “epic of freedom,” describing the movement as “mythical and heroic.” Twenty years later, he no longer describes what he did in such a grandiloquent way and has apologized to some of his victims. In 2020, Colombia’s Truth Commission published one such public apology from Mancuso to the family of Indigenous leader Kimy Pernía Domicó, who was killed in 2001 and whose body disappeared in the Sinú River. “We should never have taken action in the war,” he told Pernía’s daughter. “I was wrong, I ask forgiveness for that, for my actions in the conflict.”

Mancuso said in one of his many statements that what he learned to do in the paramilitary groups was create “a theater of terror,” one in which you not only had to kill, but also to sow fear into everyone left alive. The man responsible for that terror has shown an eagerness to continue talking about how he put the theater together. And, above all, to reveal who the actors were.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.