Women seeking justice: The effort to translate the human rights struggle into law in Colombia

In 1987, Yanette Bautista lost her sister at the hands of Colombian state agents. Now, she is spearheading a bill to protect the women who have dedicated their lives to searching for their missing loved ones in a country where at least 200,000 people have been disappeared

For weeks now, Yanette Bautista has had her bag ready to rush to the Colombian Congress. She is on the phone in case the moment arrives when Colombian legislators finally decide to prioritize the bill that she is spearheading; the proposed legislation has been her whole life: it promotes the rights of women searching for missing persons. But every day, something else comes up; last Wednesday, when it was scheduled to be the first issue discussed, a cab drivers’ strike in the country got in the way. The bill keeps moving lower down the agenda or debate is postponed, as if forced disappearances did not matter, as if it were a minor issue, even though the most conservative estimates say that 120,000 people have been disappeared in Colombia. The Truth Commission puts the figure at 200,000 victims. “We have the record in Latin America,” Yanette says emphatically at her foundation’s headquarters in Bogotá.

In 1987, she was an executive secretary at a multinational company, and the fight for human rights was not part of her plans. That changed on August 30 of that year, when members of the army disappeared her sister Nydia Erika on the day of her 12-year-old son’s first communion. Nydia was an M19 militant, and armed men from Brigade XX took her to a farm where she was held captive, tortured and sexually assaulted. Her body was found days later on a road near Bogotá. She was buried in an unmarked grave, and the family could only be certain of her identity over a decade later. The struggle for justice is still not over; the perpetrators are still at large.

“My sister’s forced disappearance confronted me with a reality that I never imagined existed… It set me on another path, because having known that reality, I could not work as if nothing had happened in this country. I was never the same,” says Yanette, now 66 years old, at the headquarters of the Nydia Erika Bautista Foundation. She created the foundation to fight against impunity, and it brings together women seeking justice. One arrives at her office after passing through Revoltosas [Rebellious Women], a clothing and jewelry store where these women make money to survive. It is a bright room where images from over three decades of protests stand out. One woman reminds us that there are more disappeared persons in Colombia than in Chile under Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship; she ends with a phrase that challenges Colombian society: “But who cares?”

Indifference, says Bautista, is the third pillar of impunity in forced disappearances. According to Bautista, the other two pillars are the negligence of the justice system, which has played a role in human rights violations; and neglect on the part of the media, which does not clarify the magnitude of this crime against humanity. That’s why she believes that it is time for Colombia to pass a law that comprehensively protects women who are still searching for their loved ones, so that they are considered the subjects of special constitutional protection and peace builders. She says women specifically because 95% of those searching for the disappeared are mothers, wives, sisters and daughters; the other 5% are fathers.

What is included in the law?

In practice, the bill asks the State to prioritize what happens to women as they search for missing persons. That is not a minor detail. They suffer threats, kidnappings, extortion, reprisals, recruitment of their minor children and sexual violence against girls who are left unprotected while their mothers search for their other children, struggle to recover the bodies, bury them and fight impunity. Yanette herself received death threats and had to go into exile.

Therefore, they want the National Protection Unit to prioritize the threats they receive. Considered peace builders, they also seek a voice in the negotiations that are progressing toward the so-called total peace, the current government’s effort to undertake simultaneous negotiations with different armed groups.

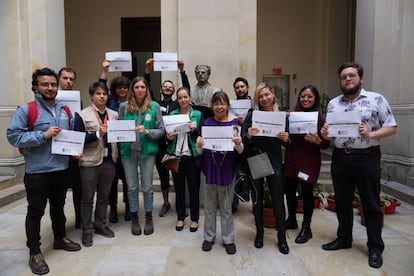

The bill, which passed its first congressional debate in May and finally reached the plenary session of the House of Representatives last Tuesday, is the work of eight women’s organizations. The proposed legislation is based on reports that they delivered to the Truth Commission — created after the peace agreements between the State and the now-defunct Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) — including one that says that each family has two searchers, totaling some 400,000 people. “On average, forced disappearance affects the lives of between five and ten family members per victim… If [one] looks at indigenous and Black cosmovision and its concept of extended family, the universe of those affected might be larger and reach 2 million people,” says Yanette, as she takes notes to answer each question in detail.

The economic lives of women searching for their disappeared relatives are often rendered invisible. Many lose their jobs for prioritizing the search for their loved ones, abandon their studies, are displaced and live poorly. Bautista’s proposed law seeks to improve this situation, and it would not have a fiscal impact on the State, because it already includes these women in existing institutions and public policies. “We are not asking that the women searching [for their missing loved ones] be treated better than others, but we are asking for priority treatment [so] that these women can dream of attending college [and of] having decent housing, health care and a pension,” she adds. Yanette herself has dedicated her life to that search; although she is recognized around the world as a leader — among other awards, she has won the Shalom Prize of the Catholic University of Eichstätt (Germany) and Amnesty International’s Human Rights Award — she will not have a pension.

After years of protesting and struggling, the women decided to write down concrete proposals. They received technical advice from the United Nations Office for Human Rights, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Pastoral Social and the Dutch Embassy. One article in the bill states that they should have tuition benefits to access higher education and loans for their families, as well as access to housing projects and specific measures to address the multiple health problems that have been aggravated by the violence they have suffered in their search for justice.

Other key parts of the bill include creating a Single Registry of Women Searching for Victims of Forced Disappearance, so that the Unit for Integral Reparation for Victims has accurate information about them; and measures for raising social awareness about forced disappearance. “If society reacted to or felt ashamed of this crime and joined our struggle, at least we would not be so alone… We have been [isolated] for a long time,” Yannette Bautista says. Last Wednesday, she was waiting for her bill — and her life’s project — to become the first one debated in Congress and in the country. But at the last minute, the congress members cancelled the meeting for the bill.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition