Colombia’s kidnapping business is booming again

Between January and March 2022, 35 kidnappings were registered in the South American country. In the same period of 2023, the figure doubled. Among the current victims is an 87-year-old man, the oldest hostage in the world

A man dressed in black, barefoot and sitting on a plastic chair speaks into the camera of his kidnappers’ cellphone. This is for proof of life. He says that he’s fine and asks his family to get the money his captors are asking for, so that they can buy his freedom.

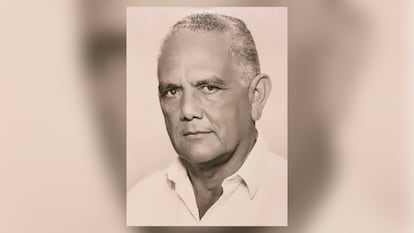

Heriberto Urbina is 86-years-old. Since April, he’s been living through his third kidnapping. The family fears for his health. The phenomenon of kidnapping has never totally disappeared in Colombia… but over the last year, the rate of incidence has doubled.

Urbina has dedicated his entire life to livestock. Until the day of the kidnapping, he worked on his farm from dawn to dusk. He was buying fuel in Curumaní – in the northern Caesar department (region) – when suddenly, several motorcycles appeared: three armed men got out and walked over to Urbina’s vehicle, pointing a gun at him. He thought it was a robbery and got out of his truck without resisting.

With the use of threats, they put him in the backseat. Two men sat on either side of him, pointing their weapons at his face. The vehicle slowly moved down the bumpy road, without any law enforcement officials noticing. Followed by the three motorcycles, they entered the mountains of the Serranía del Perijá. Once they were far away from the abduction site, the kidnappers burned Urbina’s vehicle and they all continued the journey on motorcycle. The family contacted the military authorities and, that same night, pilots flew over the area with planes. The next day, they used a helicopter… but in such vast terrain, they couldn’t find a trace of the farmer.

April 24 was the beginning of a tortuous transition – not only for Urbina, but also for his family. The biggest concern was that his already-deteriorated health could worsen, due to pre-existing conditions that afflict him. “The anguish is that these men have kidnapped a person whose days are numbered,” one of his relatives laments.

The kidnappers are demanding a sum of money that the family doesn’t have. “He’s going to die and it’ll be your fault,” they say threateningly, whenever they call up Urbina’s relatives. Although the captors have identified themselves as being members of the Clan del Golfo (a paramilitary group), the community points to the ELN guerillas as the perpetrators of the kidnapping. The ELN hasn’t made a statement regarding the case, but members of the Clan del Golfo have unofficially denied their involvement in the kidnapping.

In 1997, Urbina experienced his first kidnapping, at the hands of ELN insurgents. He was held captive for nine months and 21 days. And, a year later, he was intercepted by FARC guerrillas on a highway, at one of the group’s illegal roadblocks. This was also for the purpose of extortion.

The most recent statistics from Colombia’s Ministry of Defense show that, between January and March 2022, 35 people were kidnapped across the country, while in the same period of 2023, it has been more than double that figure: 71. The Urbina kidnapping is not included in this figure, because it happened in April . The same report indicates that, in all of 2021, 160 kidnappings were perpetrated. In the following year, there were 222, representing an increase of 38%.

In Colombia, kidnappings can be for political purposes, such as the recent case of policeman Dayan Edmundo Poto – which the ELN has admitted to – and for extortion purposes, such as that of Heriberto Urbina. Both kinds of kidnappings have increased in the last two years. The government and the ELN have been in peace negotiations, although no ceasefire has been reached. According to Luis Trejos – a professor at the Universidad del Norte and a specialist in violence and peace studies – political kidnappings are taking place for control of territories. These abductions tend to last for shorter periods, while extortion-motivated kidnappings are quieter and longer.

At its worst, Colombia reported up to 3,500 kidnappings a year, when guerillas and paramilitary groups used extortion to finance their wars. The FARC was responsible for 33% of the kidnappings, according to a report by the National Center for Historical Memory. Kidnapping not only implies the loss of freedom, but also “daily coexistence with death, imprisonment in undignified conditions, a loss of autonomy, the elimination of privacy, the separation from loved ones [and] the abandonment of one’s own projects… along with feelings of uncertainty, loneliness, fear and hopelessness,” notes the final report of the Truth Commission, which found that, during the armed conflict in Colombia, there were around 80,000 victims of this crime.

With the signing of the peace agreement between the government and the FARC, kidnappings – and all forms of violence – were substantially reduced. But Caesar is one of the departments where this phenomenon occurs the most. In the area where Urbina was kidnapped, the Clan del Golfo, the ELN guerrillas and dissidents from the now-dissolved FARC are present. The Office of the Ombudsman has established informal security and private surveillance mechanisms to help protect individuals who are affiliated with farming on large plots of land.

Urbina’s family hasn’t been able to reach an agreement with the kidnappers, because the ransom they are demanding is exorbitant, greatly exceeding the value of the assets they own. And, with the terror that this event has generated, no one even wants to buy land, invest in the countryside, or purchase cattle, according to residents of the region. Ombudsman Carlos Camargo has stated that he is concerned for Urbina’s situation, given the victim’s age and state of health.

“The kidnapping is a consequence of the continuing armed conflict in the regions, where the confrontations [continue, as does] the violation of the civilian population’s human rights,” Camargo explained.

Why have kidnappings skyrocketed?

The overproduction of the coca leaf in Colombia caused sales to decline on the black market, unleashing misery across cultivation zones. The illegal armed groups that run the illicit planting and narcotics-processing businesses have resorted to another source of income: kidnapping. This is one of the hypotheses of Luis Trejos:

“Drug trafficking is a chain of several links… everyone eats from it. When coca-planting and processing stopped, various links were left without income. This caused many criminal organizations – which once derived the bulk of their income from drug trafficking – to resort to kidnapping,” he explains.

Trejos believes that the deterioration in the security situations that began during the presidential administration of Iván Duque (2018-2022) has also had an influence – old criminal practices that seemed to have been overcome have reappeared. However, he emphasizes that kidnapping should not be seen separately from the crime of extortion, which is also on the rise. The expert notes that kidnappings for the purpose of extortion are also taking place in territories where coca is not produced. Across the board, criminal groups are looking for other forms of financing.

Until a few days ago, Urbina was the oldest kidnapped person in the world… but now, 87-year-old rancher and lawyer Sanín Mena has just been kidnapped, also in the department of Caesar. In the municipalities of this region, silence reigns – comments are made anonymously.

“Here, at seven at night, there’s not a soul left on the street. What we’re experiencing is terror,” a community leader – who does not wish to be named – tells EL PAÍS. In a post circulating on social media – whose origin is unknown – the following threat can be read: “We’re going to start the cleaning. Get ready, Chiriguaná, Curumaní, Pailitas,” in reference to cities in the region.

“We thought that the kidnapping was a thing of the past… but then, surprise!” says a resident of Chiriguaná. Some Colombians believe that the country has regressed; that violence and war are returning to start a new cycle. That it’s still not the time or place for peace.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.