Sandro Castro: Fidel’s grandson is an influencer

At 33, with nearly 115,000 Instagram followers, he is the most talked-about Castro in Cuba today and one of the most potent symbols of the revolution’s decline

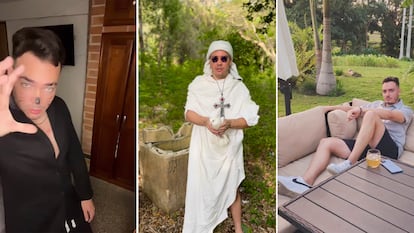

Fidel Castro has a grandson who’s an influencer. Not one with military prowess, but one who makes social media reels. Not dressed in olive green, but in Real Madrid soccer jerseys. The “new man” of the Cuban Revolution is now a content creator, with nearly 115,000 followers on Instagram, who posts challenges, listens to reparto music, and loves cats and Cristal beer.

Some say he is, more than 60 years later, the worn-out grimace of Castroism, or its disfigurement. Others argue he’s simply a product of the natural course of Cuba’s failed social project. And there are those who claim he might be the valve that finally bursts and sparks change in Cuba. The only certainty is that Sandro Castro, with a cellphone — not a machete — in hand, is today the most talked-about living Castro on the island.

Sandro, 33, was born when his grandfather was 65 — that is, a Fidel still in full physical strength, channeling all his political rhetoric into telling Cubans that hard times were coming, but that the country would know how to overcome the crisis. Cuba had just lost the USSR as its main trading partner and was entering the long night of the Special Period — one it has, in many ways, never left.

Sandro — who proudly smokes Habanos, drives a Mercedes-Benz, and takes flights in small planes — was born and raised in a country of blackouts, food shortages, the Cuban rafter crisis, the July 11 uprising, and thousands of political prisoners. He’s watched much of his generation emigrate in the largest exodus since the triumph of the revolution.

His birthday is December 5 — the same day as imprisoned artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara. He listens to Bebeshito and Bad Bunny, and in one of his many reels, he used a line from the Puerto Rican artist: “A round of applause for mom and dad, ‘cause they really crushed it.” His followers replied instantly: “And another round of applause for grandpa — he really crushed the country.”

He is the son of Rebecca Arteaga and Alexis Castro Soto del Valle, a telecommunications engineer and one of Fidel’s five children with Dalia Soto del Valle, the woman who stood by the commander until his death. Very little is known about the family. This is something the former leader sought from the moment he came to power: to keep the secret of their privileges safe. It is even said that his family barely interacted with that of his brother Raúl Castro.

Sergio López Rivero, a professor of Cuban history who has studied the historical process of Castrofism, argues that “the extreme secrecy surrounding the Castro family is one of the fundamental chords that shape the construction of the revolutionary myth in Cuba.” According to Rivero, the purpose was not only protection but also to provide “legitimacy to the regime,” built on suppositions of “trust and certainty.”

Few Cubans know what Cuba is like inside Punto Cero, but most can imagine it. It is a residential complex located in Havana’s Playa neighborhood, where the family resides — and where Sandro lives as well.

Idalmis Menéndez López, former partner of Sando’s uncle Álex Castro, told the Miami press from Barcelona, after breaking with the family, that Sandro — Dalia’s favorite grandson — grew up with his parents in an apartment adjacent to his grandparents’ house. It was there that Idalmis realized there was more than one type of cheese and wine, and where she tasted salmon for the first time.

Fidel Castro is said to have been lavish in his private paradise in Cayo Piedra, yet stubbornly refused to replace his Mercedes Benz 500 SEL. The writer Norberto Fuentes, who was close to the family, recalls seeing him once with a hole in the sole of his boot. Cubans knew a Fidel dressed in olive green who claimed to earn 900 pesos a month. “He kept his personal life separate from the country and everything else,” says Fuentes.

But his offspring have gradually worked to demystify that image. His son Antonio Castro was spotted sailing yachts around the Greek islands of Mykonos; his niece Mariela Castro was seen eating lobster and sporting Louis Vuitton handbags. Other family members — like Raúl Guillermo, nicknamed “El Cangrejo,” a grandson and head of Raúl Castro’s personal security — have openly enjoyed lavish parties, outings, and flaunted their rental mansions. None of this would seem excessive, if it weren’t a family built on a discourse of austerity, one that has demanded the people endure crisis, sacrifice themselves, and has normalized misery.

Sandro is probably the closest the Cuban people have ever been to truly knowing the Castro family from the inside. In recent years, he hasn’t held back from showing off his luxury cars, throwing private parties in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, or flaunting his nightlife persona at EFE Bar, a venue he owns in the heart of Vedado. He didn’t even try to hide celebrating his birthday while almost all of Havana was experiencing a blackout.

He openly toasts with whiskey, bathes in Cristal beer (which he’s renamed and popularized as “Cristach,” referencing his vampire character on social media). He doesn’t hide the fact that his gas tank is full amid fuel shortages, nor did he hesitate to promote one of his parties while the entire country was in national mourning over the deaths of 13 young recruits.

Sandro’s Cuba is not his grandfather’s Cuba. Fidel’s country criminalized reggaeton, while Sandro’s Cuba capitalized on his own local version, the reparto. Fidel demonized the Americans, but his grandson dresses up as Batman and celebrates Halloween. Sandro exists in the Cuba of the internet, not in the Cuba that deprived its citizens of connection for decades and, therefore, of understanding what the outside world was like. Broadly speaking, Sandro is what his grandfather did not want Cubans to be, what he did not design in the blueprint of his revolution. Some believe that Cuba’s Trojan horse has arrived.

“In the midst of the current economic crisis, Sandro Castro’s behavior seems more harmful to the regime founded by his grandfather,” says López Rivero. “But the danger extends because in the Cuba Sandro Castro lives in, the economy is not the only problem. The lack of expectations and the feeling of being unprepared to handle unexpected challenges have worsened the crisis of legitimacy on the island.”

Betraying his family name?

Sandro has pushed the limits — almost as if betraying his own last name. In some of his videos, he has slipped in veiled criticisms of the regime, like joking about rising internet prices: “I’m going to get my friend [Cuba’s state-owned telecommunications company] ETECSA drunk on Cristach to see if she goes crazy and starts handing out data,” he said.

He’s also referenced the constant blackouts in Cuba: “If I catch you, I’ll treat you like the UNE [Cuba’s Electric Union] — every four hours, seven days a week.”

He’s joked “there’s no chicken;” displayed the U.S. flag in the background of his clips, and even dared to ask Donald Trump to “give opportunity and life to the migrant” in the middle of the largest Cuban exodus in decades.

Sandro, who gains followers by the day, has left Cuban users bewildered. Some have even started saying that, of all the Castros, they’d prefer Sandro as the next president of Cuba. Some feel he’s more relatable than anyone else with that last name — more like the people than like his own family. Others ask what his uncle Raúl Castro or current president Miguel Díaz-Canel must think of him. Some tell him: “If your grandfather could see you now…” Many are offended by his arrogant attitude.

“Sandro is viral because he’s a Castro, but that shouldn’t surprise anyone,” says Cuban citizen Anay González Figueredo. “While the average person navigates blackouts, shortages of medical supplies, and censorship, this scion of the elite positions himself as a post-revolutionary influencer — protected by a system that criminalizes dissent but barely flinches at his insolence, signed with a famous surname.”

Juan Pablo Peña, a young Cuban who says he was born amid slogans, believes Sandro “isn’t a mistake of the regime, but its embodiment.” “He’s the inherited face of a ruling class that co-opted the language of social justice to establish its own dynastic privilege,” he says.

Not long ago, Juan Pablo had a conversation about the country’s situation with his father, a 60-year-old former soldier. “He told me something that stuck with me — that Cuba has become exactly what Fidel never would have wanted. Hearing him say that, I realized he was still trying to defend something that was rotten from the start.”

The young man believes Sandro is a withered caricature of the Cuban Revolution. “The dictator’s grandson turned influencer is the terminal stage of a narrative that once promised to be redemptive and ended up being parasitic. Sandro is not just privileged — he’s a grotesque satire of Castroism. Sandro is the product of a social experiment that failed, but refuses to die,” he says.

Sandro Castro provokes ire both from critics of the government and from its loyalists — the former accuse him of “mocking” the people, the latter of betraying Castroism. Sandro holds no political office; he describes himself instead as an “entrepreneur,” an “ordinary guy,” and a “young Cuban revolutionary.” He has even adapted José Martí’s Versos Sencillos (Simple Verses) into Instagram reels. But he has already drawn the attention of several regime mouthpieces, who see him as a double-edged sword. “Sandro has no affection for his grandfather, nor does he respect his memory,” said pro-government intellectual Ernesto Limia. Others have labeled him an “idiot” or an “ideological enemy.”

People believe that Sandro exists because his grandfather no longer does — or better yet, that Sandro is proof of his grandfather’s absence. And by extension, that Raúl Castro, now 94, won’t be around much longer either. The name — now in its third generation — seems ever more distant from the Moncada Barracks, from the epic of 1959, and from the revolution’s founding myth. As if Sandro were somehow less of a Castro. As if the surname were fading, and Cuba were beginning to be inhabited by other names. Some have asked if this is the end. But there’s still no answer.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.