Corsica’s mafia: Blood, silence and territory

Some 20 clans divide up the island and exploit its natural and economic resources through intimidation and violence. Civil society has decided to stand up to them

On December 5, 2017, cameras at Bastia Airport, on the French island of Corsica, captured a man wearing a latex mask walking behind two other men. One of them had just landed on Air France flight 4462 from Paris. The other one was waiting to drive him home. They were Tony “The Butcher” Quilichini, recently released from prison, and his friend Jean-Luc Codaccioni, who was returning from a prison furlough in the capital. The man following them pulled an AK-47 with a retractable stock from his bag and opened fire. Quilichini was hit 21 times in the back and the assailant finished him off with a 9mm shot to the head. He died on the spot. Codaccioni, who was hit five times, died in hospital on December 12, 2017. The two had actually been dead for 10 years.

The blood of the fathers will stain their children, the old Corsican proverb goes, explaining an endless cycle of violence. When someone decides to kill on this great mountain in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, the place with the highest homicide rate in France (3.7 per 100,000 inhabitants) and one of the most heavily armed stretches of land in Europe (350 weapons per 1,000 inhabitants), they are certain that sooner or later their children will seek revenge. It is an inexorable logic that will operate in a loop until the extinction of the human race. Or at least, of the families who fought for centuries over this territory of 351,000 inhabitants.

The airport killer was Christophe Guazzelli, 32. Tall, handsome, with captivating blue eyes. Raised in bourgeois comfort, his family sent him off the island for years to keep him away from the poison. But in 2009, the men at the airport had murdered Francis Guazzelli, his father and one of the founders of the Brise de Mer (named for the bar in the old port of Bastia where they met), Corsica’s first modern mafia. His son had no choice. He waited 10 years to ruin his life, guided only by two goals: revenge and restoring his father’s organization by eliminating the rival clan.

The murder was a turning point in the history of the Corsican mafia, which is now immersed in a process of fibrillation almost unseen to date. Some 20 clans are dividing up the territory horizontally, without a supreme boss, according to a disturbing report by the intelligence services of the criminal investigation force published by Le Monde this week. It comes just as French civil society, politics, and the judicial system are beginning to call the mafia by its name. “There were cultural reasons why the state didn’t want to recognize it. France is the land of human rights. How could that exist here? There have been passive and active accomplices, many public officials who didn’t want to call the disease by its name. But we won the semantic battle. There’s a mafia system that we didn’t invent, we only described it,” says Léo Battesti, a former nationalist activist and current founder of the association Maffia No, a vitta iè (No to the Mafia, Yes to Life).

The clans — the Mattei, the Pantalacci, the Mocchi, the Africans — are part of island life. “Most of them have penetrated all sectors — political, social, and economic — on the island and seek to dominate the legal activities they find most profitable,” writes Sirasco (the Criminal Intelligence Service of the Judicial Police). They have interests in construction, catering, hospitality, shipping, and even real estate. The balance between these groups remains fragile and can, at any moment, be shattered by open and violent conflicts where mutual hatred has simmered for decades. And then, the dead return, businesses explode. “If my son tells me he’s going to open a bar here, I’ll say no. If he asks me about a tourist business, a nightclub, a construction company, I’ll answer the same. Even if he wants to deal in public works. So what’s left for him? Join them, play by their rules, or leave Corsica,” says a magistrate.

Two criminal powers — the Brise de Mer gang in the north and the clan of Jean-Jérôme Colonna, alias “Jean-Jé,” in the south — structured organized crime on the island for about 20 years and imposed a social control that still endures. Jean-Jé’s accidental death in 2006 and the fratricidal war within the Brise de Mer gang between 2008 and 2009 ushered in a first phase of transition that culminated in the murder at Bastia airport in 2017. In the south, the Petit Bar gang took up Jean-Jé’s legacy. According to Sirasco, the situation is once again “particularly unstable.” The document notes that “for several months now, a broad reshuffling has been taking place, shaking local balances and raising fears of an escalation of tensions.”

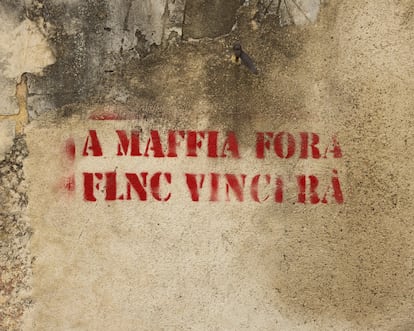

Prosecutor Jean-Philippe Navarre, with a shaved head, a boxer’s build, and an unwavering determination in his gaze, welcomes EL PAÍS in his office at the Bastia Palace of Justice. A veteran of organized crime counter-defense departments in places like Marseille, Lille and the Antilles, the prosecutor has a photo of graffiti on one of Bastia’s streets on his bookshelf. Next to his name are two drawings: a suitcase and a coffin. One thing or the other, the threat implies. Affectionate messages, he jokes. “It’s important to understand that a criminal from the continent, a drug dealer who has become a millionaire through drug deals, dreams of taking his money to Dubai, owning a hotel, a villa, girls... The Corsican criminal will have that too, with connections and resources. But his real dream is to return every summer and have people lower their gaze when he sits on the bar terrace,” he notes. “When they are disrespected, when they are rejected, we will have gained something: that is the work of the justice system, the state, national education, and collectives. Everyone must mobilize to change things,” he says, pointing to education in schools as the first link in the chain of change.

Corsica, with its strong independence urges, rooted in the island’s Genoese origins, has always been a foreign object in one of Europe’s most centralized countries. Movements like the Corsican National Liberation Front (FLNC) terrorized the population with bombs and murders for years to assert territorial sovereignty. The 1960s and 1970s were filled with blood and lead. And the role of the prefect (government delegate) is never easy in places where the state is seen as a colonizer, an oppressor.

In the waiting room of the prefecture, there is a poster for a concert by the Avignon Orchestra, which performed on February 6, 1998, in Ajaccio. That day, Claude Érignac, then a representative of the French state in Corsica and a great music lover, dropped his wife off at the theater door, went to find a parking space, and then walked back to the theater. Before he could make it, a nationalist terrorist, Yvann Colonna, shot him three times in the back and killed him. The face of his killer, now a national hero, is plastered everywhere in Bastia and Ajaccio even today.

— Hello, come in, says Jerôme Filippini, prefect of South Corsica since 2024.

Filippini is direct, transparent. He doesn’t use euphemisms. There is a mafia, yes. It’s in politics, in the streets, in society. A few months ago, when the first demonstration against this phenomenon passed in front of the prefecture, he took to the streets and climbed onto a truck with a megaphone to encourage the population to fight, to break their silence. “I’m not a fatalist; I don’t believe that societies are condemned by history. Nor that individuals are condemned by the society to which they belong. If everyone wants it, we can get rid of these people,” he points out. It’s difficult. On the island, no one speaks. When a crime occurs, it’s almost impossible not to know one of the parties, directly or indirectly. Witnesses fall silent when the police arrive, and on trial day, not a single juror shows up. “The first thing is trust in the state and the police. For reasons inherited from the past, there has been a distrust between Corsica and the Republic. And if it’s not restored, crime will win. We must embrace reporting crimes, speaking out. But doing so with confidence. And that will take time. But it will also require tools that allow for the confiscation of organizations’ assets,” he says.

France has passed tough new laws against drug trafficking: high-security prisons, solitary confinement, streamlined prosecutions… and the creation of a new Prosecutor General’s Office dedicated to organized crime. But Corsica remains a difficult ecosystem to pigeonhole. “It’s a theater of shadows. We have a hard time seeing things. The mafia has always existed. There has always been a porosity between bandits and political and economic power. It’s a tradition dating back to the 19th century: domination by force, violence, murder. What’s new is the anti-mafia groups, who have won a semantic battle,” analyzes Léo Battesti.

His years of nationalist activism, also through violence, made him understand the absurdity of that armed struggle, whose leaders, in many cases, ended up sitting at the same table as organizations like Brise de Mer to divide up the island. “It was a mistake. We gave them an almost political character. But today the situation is chaotic. All the actions being carried out today against businesses, ships, real estate businesses… are part of that tradition of pressure on economic sectors. The entire island is under pressure. Even those who say they aren’t: those, the most.”

The wave of attacks on certain economic sectors has been particularly virulent this year. The Corsican Chamber of Commerce called for an end to the violence two weeks ago in a statement. It was the second time. They were concerned, of course, about the economy, in a region with an unemployment rate (6.4%) lower than the French average (7.4%) and enormous tourism potential. That is also the problem. “It is a fact that, far from fading or receding, this wave of crime continues to grow and spread. No economy, no human society will be built from ashes or misfortune,” the statement reads.

In 2024, there were 364 acts of violence (arson or explosives) against Corsican companies that refused to pay or accept clan members as business partners. One per day. It was also the year of murders: 18. Six boats burned in the ports of Calvi, Ajaccio, and Saint-Florent. But it’s difficult to know how many there really are. “These are gray figures because there are very few complaints. Today, it’s no longer a question of asking for an envelope at the end of the month, but of becoming a partner in the company under threat, sometimes simply by their presence, without even verbalizing this violence. This makes it more difficult to detect,” notes Colonel Charles-Guillaume Lacoste at the Ajaccio Gendarmerie headquarters.

The struggle of the forces of law and order — the Gendarmerie and the National Police — is like the myth of Sisyphus. No one dares to say whether it’s possible to win. Everything is too intertwined. It’s difficult to define the mafia sphere. “It’s integrated into society, that’s the difference. It’s not a group of drug traffickers who have nothing to do with the landscape. The mafia here acts on political power, on economic power, and is part of it. There’s pressure on those sectors, as well as on society. It’s very unique. Corsica is a small island. Everyone knows each other. In the same family, there can be a politician, a mafioso, a businessman... It’s difficult to know if it’s just a family tie or infiltration,” Lacoste analyzes.

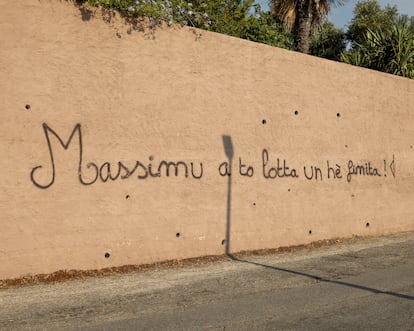

The fight against the mafia also requires heroes and martyrs capable of silencing the guns with their lives. In Sicily’s toughest years against Cosa Nostra, they were Peppino Impastato, Giovanni Falcone, and Paolo Borsellino. Corsica is now plastered with the face of Massimu Susini, murdered on September 12, 2019. The man, then 36 years old, confronted the clans that were beginning to threaten Cargese, his hometown and a crossroads between nationalist movements — to which he belonged — and organized crime. One morning, just after 8:00 a.m., as he was opening his beach bar, a man stood in some bushes with a rifle with a telescopic sight and shot him four times with bullets that could have brought down a bear. One of them pierced his collarbone and severed his airway.

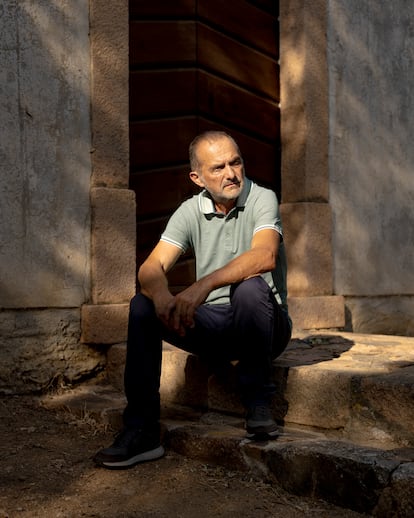

The killer fled. As is often the case, the culprit was never found, recalls Jean-Toussaint Plasenzotti, Susini’s uncle and founder of the association that bears his name. “They thought that by killing Massimo they would terrorize the town and be able to continue their drug business. But the opposite happened,” he notes next to the small monument commemorating his nephew, a few meters from the spot where he was murdered. Since that day, about five years ago, many things have changed.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.