Secret history of the conclaves: The internal battles of the last 10 papal elections

The voting process to elect the pope has its own dynamics, and understanding how it has worked over the past century provides clues to better comprehend what may happen now

What happens in a conclave is not only secret — though more or less everything eventually becomes known — but also deeply mysterious. Votes shift and fluctuate until they finally converge on a single name, which is often not among the initial favorites. Alongside the influence of the Holy Spirit, far more earthly factors come into play — patterns that tend to repeat themselves.

To understand how these peculiar dynamics work, and to get a sense of what might unfold starting this Wednesday in the election of Francis’ successor, it’s helpful to look at what happened in the last 10 conclaves, drawing on the work of scholars Giancarlo Zizola and Alberto Melloni. These span from the 20th century to the present day.

1903: Pius X

This conclave is famous because it was the last time a foreign power exercised a political veto — a right that, until then, had been held by the most powerful Catholic nations in Europe. On the very day of Leo XIII’s death, the Austro-Hungarian foreign minister sent a telegram to his ambassador to the Holy See, instructing him to use “exclusive authority,” if necessary, to block the Italian Cardinal Mariano Rampolla, who was seen as hostile to Austrian interests.

The conclave, which required seven votes, began with 62 cardinals, making 42 the two-thirds majority needed for election. Who led in the first vote? Rampolla, with 24 votes. Giuseppe Sarto — who would eventually be elected and take the name Pius X — received only five. The election soon turned into a standoff between the two, and the Austrian cardinals, tasked with exercising the veto if needed, feared Rampolla might prevail. But they hesitated to invoke it — by then, it was already seen as anachronistic.

Eventually, Austrian Cardinal Jan Puzyna rose to speak and read the formal declaration of the veto, but he spoke so softly that almost no one heard him. When he was asked to repeat it, the chamber erupted in outrage. It’s unclear whether the veto had any real effect, as Rampolla had already reached his peak in support. In any case, Sarto was reluctant to accept the papacy and had to be persuaded. One of his first acts as pope was to reform the conclave rules and abolish the right of veto altogether.

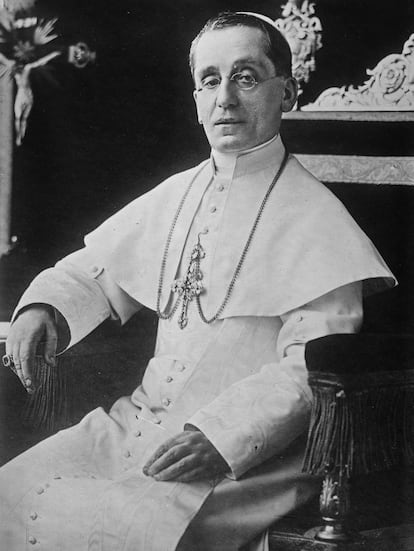

1914: Benedict XV

Pius X died on August 20, 1914, the very day Germany invaded Belgium, marking the start of World War I. The timing shaped the conclave in profound ways: not only did the 57 cardinals struggle to reach Rome, but the priority was to elect a pope unaligned with any of the warring nations. Italy, at the time, was still neutral.

The conclave lasted four days a required majority of 38 votes. The pendulum effect — so typical from one papacy to the next — was in full swing. Giacomo della Chiesa, who would take the name Benedict XV, represented a more liberal shift and something of a correction for the “losers” of the previous conclave. He began tied with Cardinal Maffi, each with 12 votes. His momentum briefly faltered after the fourth ballot when his opponents redirected their support to Cardinal Serafini. But Della Chiesa steadily gained ground and eventually hit the exact threshold of 38 votes on the tenth ballot.

The margin was so narrow that the Roman Curia faction, skeptical of the outcome, demanded confirmation that he hadn’t voted for himself — a rule still in place at the time but now obsolete. Because each cardinal marked his ballot with a secret personal symbol, it was possible to verify his vote. It was confirmed that Della Chiesa had voted for someone else and he was elected.

1922: Pius XI

It was the longest and most hotly contested conclave, lasting five days and requiring 14 ballots. Fifty-three cardinals participated, with the necessary majority set at 36 votes — though the American cardinals were unable to arrive in time by boat, as only 10 days were allowed for travel to Rome.

The clash during this conclave was a struggle between reverting to a more conservative Church, as led by Pius X, or continuing the openness promoted by Benedict XV. The election was repeatedly blocked, with a range of candidates considered, including a non-Italian, Dutch Cardinal Van Rossum.

In fact, the eventual winner, Achille Ratti, only received five votes in the first ballot — he was the fourth or fifth choice. His support didn’t gain momentum until the ninth ballot, but from there, his votes steadily increased.

The conservative bloc and the Curia both opposed each other’s candidate, leading to several attempts to find a suitable compromise. Eventually, they settled on a third candidate, which is often the outcome of many conclaves.

According to later accounts, the conservative faction backed Ratti after securing a promise that the opposing candidate, Cardinal Pietro Gasparri — who was favored by the other side — would not remain in office as Secretary of State.

Such political maneuvering is officially prohibited and carries the risk of excommunication. However, Gasparri, the victim of these tactics, later wrote in his memoirs that at least two of the conclave’s key strategists engaged in these practices. Despite this, Gasparri went on to serve as Secretary of State for another eight years.

1939: Pius XII

This conclave was the quickest of the contemporary era and one of the most anticipated. It required only three ballots, as the frontrunner, Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, was the clear favorite, and the world situation was dire, with World War II looming.

Pacelli had served as nuncio to Germany, lived in the United States, and had effectively led the Vatican during the final years of Pope Pius XI, when the pope was ill. Sixty-three cardinals gathered in Rome, waiting 18 days for their colleagues from the United States to arrive. This marked the first time all the existing cardinals could participate in a conclave.

The Curia, to which Pacelli belonged, controlled 44% of the vote. He secured more than 30 votes on the first ballot, quickly gaining momentum, while his opponents were divided. One of them, Cardinal Maglione, transferred his votes to Pacelli and later became his Secretary of State.

1958: John XXIII

After a long papacy that marked the end of an era in a rapidly changing world, the Church found itself disoriented. It wanted a transitional pope— a recurring type of pontiff when the cardinals were uncertain of the direction to take. This was a leader who would serve for a short time while the situation became clearer. To fulfill this role, the chosen pope had to be quite elderly, and Angelo Roncalli, elected as Pope John XXIII, was 77 years old.

The conclave lasted four days and involved 11 ballots, with 51 electors and a majority requirement of 34. The process dragged on because the opposition to Roncalli, the so-called “Roman party of the Curia,” was divided and couldn’t agree on a single candidate. One of the challengers was the Armenian Pietro Agagianian, who had long been in the Curia for years, but the paradox was that the non-Italians didn’t want a Vatican insider.

John XXIII, in the end, served only five years, but despite the brevity of his papacy, he revolutionized the Church by convening the Second Vatican Council, a landmark moment of openness and renewal. He became the first truly beloved and popular pope of the modern era.

1963: Paul VI

The Second Vatican Council was left unfinished when John XXIII died, and the subsequent conclave was split between those wanting to continue his reforms and those seeking to reverse them — the same situation seen today. By this time, the conclave had grown to 80 cardinals, with a required majority of 54 votes. It also marked the lowest percentage of Italians in the College of Cardinals up to that point — only 35%.

The election — over six ballots — was tense, with two blocs locked in a standoff, refusing to budge. Montini, who would later become Paul VI, was supported by the pro-council faction but opposed by the conservatives and the Curia. He had two main rivals in the first round of voting, and one of them transferred his votes to him in the third round. Despite this, he still fell short of a majority, leading to a deadlock.

According to later accounts, the impasse was broken by an unusual intervention from Cardinal Gustavo Testa, a close friend and collaborator of John XXIII. Testa publicly reprimanded some members of the conservative faction for their intransigence, urging them to compromise for the good of the Church. This created a tense atmosphere, with heated exchanges of reproach. In the end, Testa’s intervention had its effect, and Montini secured a narrow majority.

1978: John Paul I

It was the first conclave attended by more than 100 cardinals — 111, to be exact, requiring a majority of 75 votes. It began on August 25 and became infamous for the unbearable heat of Rome. The Vatican building, poorly equipped to handle such a large group, forced the cardinals to sleep on cots around the Sistine Chapel and in the corridors, with only a jug of water nearby and few bathrooms available. This grueling experience was one of the reasons why John Paul II later built the current residence at Santa Marta.

Opening the windows was strictly prohibited to maintain the secrecy of the conclave, but in desperation, one cardinal even broke a window to get some fresh air.

The voting began with scattered results, and it looked like it would be a long conclave. However, Albino Luciani, who was eventually elected as John Paul I, quickly emerged as one of the frontrunners. From the third ballot onward, he rapidly gained support and secured an overwhelming majority of more than 100 votes. Despite his success, Luciani appeared distressed and struggled to accept the role, according to those who witnessed the proceedings. Tragically, he passed away just 33 days later. He chose the name John Paul I as a tribute to his two immediate predecessors, signaling his intention to follow in their footsteps.

1978: John Paul II

In the extraordinary year of two conclaves, the cardinals convened once more in the Sistine Chapel in October. Cardinal Siri, one of the leading candidates during the election of John Paul I, was given a second chance and emerged as the top conservative contender. However, a pivotal misstep would go down in history as potentially costing him the papacy: he gave an interview under the condition that it would only be published once the cardinals were already inside the conclave. Unfortunately, the interview was made public the day the cardinals entered, and everyone was able to read with alarm some of his opinions, which were too radical for the more moderate voters.

Even so, the conclave was a contest between Siri and Benelli, who each had around 30 votes. Many scattered votes remained, including five for a certain Polish cardinal called Karol Wojtyla. After the fourth ballot, the standoff remained. Siri appeared to have reached his ceiling: he was just four or five votes short of a majority, but was unable to attract additional support. That night, Wojtyla’s candidacy began to solidify, and by the next day, it rapidly gained momentum.

2005: Benedict XVI

After 27 years of John Paul II’s pontificate, with uncertainty surrounding the future direction of the Church, the clearest candidate for succession was his close ally, German Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. He offered doctrinal certainty and knowledge of the Curia. The conclave was swift, lasting only four votes, and Argentine Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio emerged as his main rival.

There are differing accounts of what transpired. Bergoglio himself, after becoming pope, shared his version of events, stating that his name was used to block Ratzinger’s election, but he was aware of a shadow candidate waiting behind him. Bergoglio refused to play along with this maneuver and made it clear that he did not want to be part of that strategy, instead casting his votes in favor of Ratzinger.

Other accounts, however, suggest that it was Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini, a prominent leader of the progressive camp and also a Jesuit, who did not have a good relationship with Bergoglio, who took an active role in directing votes toward Ratzinger. Martini reportedly moved between the tables during mealtimes, ensuring that the votes were passed on to Ratzinger.

2013: Francis

In the last conclave, once again with 115 electors, Bergoglio entered as a favorite, having been considered a strong contender in the previous election. However, his momentum seemed to wane in the days leading up to the conclave. The Italian media had rallied around Cardinal Angelo Scola, a disciple of Ratzinger, who was widely regarded as the frontrunner and practically seen as the next pope. In fact, the Italian Episcopal Conference even issued a congratulatory message for Scola after the “fumata blanca” (white smoke) was seen, mistakenly believing he had been elected.

However, in the first ballot, which revealed the real support after weeks of speculation, Scola received about 25 votes (compared to about 12 for Bergoglio), and it became clear that he did not have the massive support that had been assumed. Moreover, his support didn’t rise from there, and the votes gradually shifted toward Bergoglio, who was elected on the fifth ballot.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.