Milpamérica, a social network for resisting the Musk algorithm

More than 74 land defenders from various First Nations have created an online space they say is free of ‘racism and neoliberal discourse,’ designed for the posting of stories from Mesoamerican lands and their diasporas

A month ago, Donald Trump appointed Elon Musk, the world’s richest man, to his incoming presidential administration. The owner of X, formerly known as Twitter, will direct the Department of Governmental Efficiency (DOGE) beginning in January, and has promised to “send shockwaves through the system.” That same day, Andrea Ixchíu, a Maya Quiché activist originally from the lands known as Guatemala who is currently living in exile in Mexico, and who is the coordinator of the Hackeo Cultural organization, launched an initiative alongside 74 other Mesoamerican First Nations human rights advocates that is designed for online resistance. They founded a social network that is “free of racist and neoliberal discourse” as an alternative to Musk’s platform. “His algorithms exclude us. In the conversation about climate change and the environment, we are not present. Social networks like X and Instagram have become filled with messages of hate,” she says in a telephone interview. Currently, the platform has 266 members and a peer-led content moderation system.

Milpamérica.org is an autonomous network for posting stories about Mesoamerica and its diasporas. The platform was created in order to connect land defenders, climate justice warriors, communities in resistance and the diaspora and dissidents who fight for Mother Earth. The idea was not only driven by Musk’s appointment. It also stemmed from users’ rumblings about how best to exchange knowledge in the digital era, and from elders’ insistence on the fact that neither governments nor corporations will solve the climate crisis.

Its call to action was mobilized through a chain of dozens of environmental activists who had become sick of mainstream social media. They penned a mission statement for Milpamérica in which they collectively named a “living solution” to climate change. “We are the communities, collectives and peoples who cure bodies — territories — spirits in times of ecocide and genocide,” states the text.

How can the internet be done differently? For Ixchíu, 37, “the innovative aspect is that it has a model of assembly governance.” Milpamérica’s open-source coding allows for the addition new functions with the goal of connection, rather than profit. It can also be fully audited by a horizontal team. “There are corporate agendas that invest millions in spreading hate on the other social networks. They are absolute masters of segregation discourse. We all notice it more in election seasons,” she says. “That is why extractivism, land dispossession and genocides are advancing rapidly. We the people have no space in these environments.”

According to a report by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Minority Issues, Nicolas Levrat, 70% of the victims of hate crimes and comments on social media come from minority groups. In addition, the report found that such groups — referring to members of the African diaspora and First Nations — are also more likely to be affected by restrictions and bans implemented by social media content moderation systems. That tendency has been exacerbated since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic through extremist groups and populist figures around the world who promote disinformation and conspiracy theories.

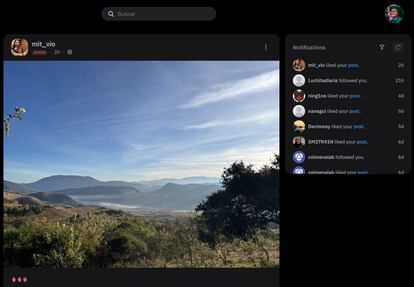

The creators of Milpamérica have designed the platform with these facts in mind. The social network’s rules are straightforward and minimal — in fact, there’s only four. The platform is a violence-free space that does not allow “racist, classist and sexist comments of any kind that violate people, communities or Mother Earth.” Its primary goal is the defense of land. It is an autonomous server that is cooperatively administered and that “does not steal or sell your information to third parties.” Finally, it extends an invitation to organize, to defend territories, bodies and spirits, to reforest hearts. The app allows users to upload photos and videos and features technological support, but does not offer a stories feature (content that is eliminated after 24 hours). Milpamérica allows users to create personal accounts, follow other users and employ filters. “It’s a social network like any other, but without all the bad,” says Ixchíu.

“One is none #CulturalHacking,” reads the bio of one of its users. “Making the radical commonsense. Multidisciplinary team of narrative action,” reads another. “There are many more people like us who want to form bonds with other communities,” explains Ixchíu, who says that there is “a lot of enthusiasm” around digital alternatives. “There has been participation from many activists from Mexico to Costa Rica and a great exchange of knowledge. Social media is changing and there are many new ways of using and even creating it.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.