Flight MH370: A third attempt to solve the biggest mystery in commercial aviation

Nearly 12 years after the plane disappeared in the Indian Ocean, the underwater exploration company Ocean Infinity is launching a new attempt to find the wreckage of the aircraft, which was carrying 239 people

The thermometers in central Beijing read minus seven degrees Celsius, but the area around Guanghua Temple is busier than usual. It’s 9 a.m. on January 3. As he does on the first and fifteenth day of every lunar month, Bao Lanfang visits this Buddhist shrine tucked away among Beijing’s hutongs, the characteristic gray alleyways of the Chinese capital. He lights two candles and leaves three golden incense sticks as an offering: “I pray for world peace, for the prosperity and tranquility of the country, and for the safe return of all those lost on MH370.”

On March 8, 2014, the life of Mrs. Bao, now 73, was tragically changed for ever. Her son, daughter-in-law, and granddaughter were returning to China after a vacation in Malaysia aboard Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 bound for Beijing. The Boeing 777 took off without incident from Kuala Lumpur, but 40 minutes later, as it approached Vietnamese airspace, it deviated from its planned route and stopped transmitting its signal.

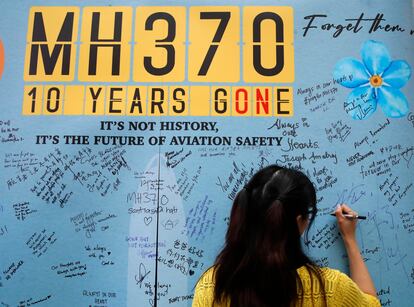

Nearly 12 years have passed, and a new search for the wreckage of the aircraft has begun. Its disappearance remains one of the greatest mysteries in aviation history: an accident from which the aircraft has not been recovered, nor has conclusive evidence been found to reconstruct what happened to the 239 people on board. The majority of the passengers (153) were of Chinese origin, and 50 were Malaysian (including the 12 crew members).

Military radar data later indicated that, instead of continuing northeast, the aircraft had turned west and crossed the Malay Peninsula. According to the official investigation, it flew for about six hours before presumably running out of fuel. Its radar coverage was completely lost over the Andaman Sea (southeast of the Bay of Bengal in the Indian Ocean), thousands of kilometers from the air corridor it was supposed to be flying along.

“Words cannot express my suffering during this time,” Mrs. Bao tells EL PAÍS. Her granddaughter would be a 15-year-old today; her son and daughter-in-law would be around 46. She barely speaks of them. She says that what she finds “most unbearable” is what came after the terrible news: the depression that engulfed her husband and ultimately consumed him. “He loved his son deeply, to the point that his grief became an illness,” she says.

The Malaysian government restarted search operations on December 30, with a commitment to “provide closure to the families affected by this tragedy,” the country’s Ministry of Transport said in a statement.

Bao Lanfang, however, believes that “reopening the case is pointless,” although she understands that some families might appreciate the gesture. She is convinced that what actually happened “doesn’t correspond at all with the incomplete information published by the international civil aviation investigation group.” She avoids delving deeper into the matter, aware that it is a sensitive issue.

Li Shuce, whom this newspaper interviewed on the 10th anniversary of the aircraft’s disappearance, has not responded to requests for an interview. In 2024, along with other family members, he met with officials from China’s Foreign Ministry to plead with them not to call off the search. At the time, Li believed his son was still alive.

Little has been revealed about the new operation. It is known that it will take place over 55 days (distributed intermittently to adapt to weather and operational conditions) in the southern Indian Ocean, and that it will be carried out by the American company Ocean Infinity, which specializes in underwater robotic technology.

It is a renowned firm in the sector, which in 2020 helped to find the remains of the iconic battleship USS Nevada on the bottom of the Pacific and, in 2022, to locate the Endurance, the lost ship of the legendary explorer Ernest Shackleton, sunk in 1915, in the Arctic. The company made an attempt to find the fuselage of MH370 in 2018, which also ended without progress.

The Malaysian Ministry of Transport has confirmed that the contract minimizes financial risk for the country, as it will only pay a maximum of $70 million in the event of a discovery. Various industry sources cited by international news agencies warn that the operation will be much more expensive, but add that a potential discovery would compensate Ocean Infinity, solidifying its position as the world’s leading underwater exploration company.

The first search took place between 2014 and 2017, in a complex international operation involving more than 10 armies and coordinated by Australia, China, and Malaysia. Its cost exceeded $150 million at the current exchange rate, and it remains the most expensive search in history. It was suspended in 2017 after covering 120,000 square kilometers without finding any objects or bodies, but with a commitment to resume if new evidence emerged.

So far, only debris believed to belong to the plane has been found on the African coast and on islands in the Indian Ocean. The passage of time has fueled outlandish theories, from a hijacking orchestrated by the CIA, Russia, or North Korea, to an extraterrestrial abduction.

After the failed attempt in 2018, Ocean Infinity received approval from Malaysian authorities in March 2025 to conduct a new search, which was suspended 22 days later due to worsening weather conditions. This time, the search area is 15,000 square kilometers. It is unclear whether the company has conclusive evidence regarding the aircraft’s location, although it claims to have worked with numerous experts to narrow down the area as much as possible.

The new campaign relies on a fleet of Hugin 6000 autonomous underwater vehicles, equipped with multibeam sonar, high-definition cameras, and laser scanning systems capable of creating three-dimensional maps of the seabed at depths of up to 6,000 meters. These drones, which can remain underwater for up to 100 hours, also send limited samples of the data they collect and receive updates from operators on the surface.

Despite technological advances, the challenge remains Herculean. Although the information stored in the black boxes should be recoverable as long as the unit is undamaged, locating them depends on the acoustic signal emitted by their underwater beacons, which are designed to function for about 30 days after impact with the sea. Once that battery is depleted — as was the case with MH370 — the only option is to visually search the ocean floor for the fuselage or fragments of the aircraft. But the inhospitable Indian Ocean features canyons over 300 meters deep, jagged walls that plunge thousands of meters into the seabed, and active volcanic zones that hinder exploration.

In the conclusions of the report presented in 2018 following the international investigation, Malaysian authorities concluded that it is “not possible to determine with certainty” the cause of the disappearance of MH370. They admitted that the deviation from the planned route “cannot be explained by a known technical failure or adverse weather conditions,” and indicated that the change of course “was probably intentional.”

Passengers and crew were exonerated, as no evidence was found implicating them — there were no signs of distress calls, rescue requests, or emergency communications before the plane lost its signal — but the possibility of “unlawful interference” was not ruled out. The government stressed that, without locating the fuselage or the black boxes, any definitive conclusion is beyond its reach.

“Although I am in the twilight of my life, my convictions have not changed,” confesses Mrs. Bao, after explaining why she religiously visits the temple every month, on the day of the new moon and the full moon. She doesn’t do it to seek answers or official explanations: “I pray for the disappeared to return; they must return.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.