The endless denigration of the natives of Tierra del Fuego: Displayed in zoos and museums in Europe

In a new book, Chilean researcher Cristóbal Marín describes the exploitation and colonization suffered by the Fuegian ethnic groups, both inside and outside their territory

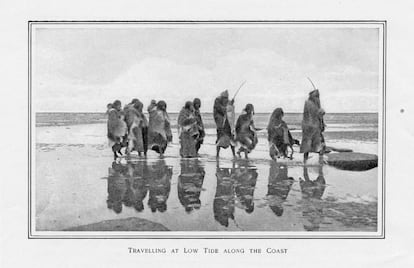

Tierra del Fuego has certainly earned its reputation for being the end of the world. The archipelago, located at the southern tip of the Americas, is feared by sailors due to the 60-mile-per-hour winds that harden the steep, snow-capped peaks. In this last continental point before reaching Antarctica, the Selk’nam, Yaghan, Kawésqar and Haush ethnic groups have lived for 10,000 years. They’re nomadic peoples, whose history has been cursed by colonizers; first by the Spanish, but mainly by French and English naturalists. In the 19th century, the latter forcibly brought many Natives to be exhibited as “savages” in the Old Continent. Much of their perverse destiny — unpunished to this day — is now collected in a book-length essay titled Huesos sin descanso (or “Bones without Rest”), which was published this past October in Spain.

“It seems like another planet. It’s a very extreme and pristine place in terms of geography,” says the author of the book, Chilean researcher Cristóbal Marín. He explains to EL PAÍS how Tierra del Fuego (translated as “Land of Fire”) has various ties between its people, the Americas, and Europe.

The pro-rector of the Diego Portales University (UDP), located in Santiago, Chile, has visited this territory several times, where ships from various latitudes sank. However, Marín learned the story of its inhabitants in London, when he was completing his doctorate in cultural studies. He discovered Andrés Bello’s translation of the travel chronicles of Robert FitzRoy, an officer of the British Navy. In it, he recounts how, in 1830, the English commander forcibly took four natives from the southern region — a nine-year-old girl, a 14-year-old boy, as well as two men, aged 20 and 26 — to Europe. The corpse of a fifth person was preserved in vinegar and stolen.

FitzRoy’s aim was to demonstrate that even the most “primitive” beings — as Charles Darwin called them — could be “civilized” according to Western standards. Since they had no immunity to European pathologies, diseases were the first to attack them. The 20-year-old Kawésqar man contracted smallpox and died a month after he was forcibly brought to London. Meanwhile, the body that arrived in the ship’s hold was sold for study to the Royal College of Surgeons. The rest of the enslaved peoples were forced to accept Christianity, speak English and adopt the behaviors of Europeans. Their captor invited his bourgeois friends to have tea, while they watched the progress of the transformation he subjected his prisoners to.

Reduced to animals

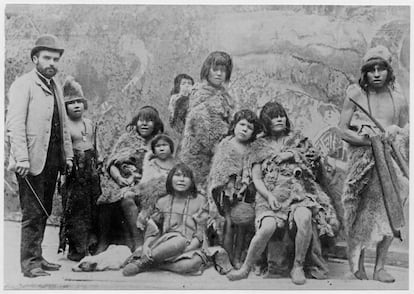

“I was taken aback by the photographs of the Fuegians dressed in Victorian clothing, [as they visited] King William IV and Queen Adelaide in 1831. They became an event in London social life,” says Marín, who was recently in Madrid presenting his research. The philosopher and social scientist also revealed that at least 100 natives — or their remains — were taken from Tierra del Fuego to Europe. After FitzRoy, Bishop Waite Hockin Stirling did so as well, in 1865. Meanwhile, the German merchant Carl Hagenbeck — famous for creating “human zoos” — ordered a violent displacement of Indigenous peoples, with the kidnapping of 11 Kawésqar (four men, four women and three children). They were forcibly exhibited in zoos throughout 1881, in France, Germany, and Switzerland.

The first stop was the Jardin d’Acclimatation in Paris, where they were visited by nearly 500,000 people. Among them were famous naturalists and anthropologists, who held special sessions in which they analyzed and measured even the genital organs of the captured women. They were then transported to Berlin in a freight train, to be displayed for five weeks at the Zoological Garden. They were then taken to Leipzig, Munich, Stuttgart and Nuremberg. On their way to Zurich, they were unable to continue, due to tuberculosis, measles and syphilis (the guards and workers at the sites where they were displayed sexually abused the women). The enslaved peoples died. Their remains were appropriated by the Institute of Anatomy at the University of Zurich.

“The conclusions of the scientific reports on the Fuegians were similar to the opinions of Darwin and FitzRoy: [according to the researchers], they represented an inferior race with limited intelligence and capacity for progress,” Marín explains. He reconstructed this history with documents from the British Museum, the British Library, and the Hunterian Museum, among others.

Another vile kidnapping was that of 11 Selk’nam individuals in 1888. They were transported “with heavy chains, like Bengal tigers” by the Belgian whaler Maurice Maitre to the 1889 Paris Exposition… the same event where works by Monet and Van Gogh were exhibited. The enslaved peoples were thrown raw horse meat and intentionally kept in filth, old clothes, and in a state of total neglect, so that they would look like “savages.”

The degrading display of Native Americans wasn’t limited to those from Tierra del Fuego. In 1879, a couple from Aonikenk (Patagonia) and their child were exhibited in Hamburg and Dresden. But perhaps the most famous case was that of the Mexican woman Julia Pastrana, who suffered from hypertrichosis (excessive facial hair) and was displayed as an abomination throughout the 1850s in the United States. After her death in 1860, her mummified body was displayed in various European cities for more than 100 years. In 2013, her corpse was repatriated and buried in the city of Sinaloa, Mexico. “The tomb was built with exceptional security measures so that, finally, her remains could rest in peace,” reads the text by Marín.

Bones without rest

As with Pastrana, the denigration of the Fuegians didn’t end with their death. Marín estimates that more than 100 bodies still remain on European soil. He identified 28 in the Natural History Museum in Kensington, 12 in the Musée de’l Homme in Paris and another 18 in the Natural History Museum in Vienna. “The most basic thing for human honor is to receive funeral rites. If [their bodies are] going to be displayed, it has to be done in a specific context, with labels that explain [the circumstances] and situate them,” the researcher argues. In 2010 and 2016, the remains of some captured Indigenous peoples were repatriated, but most of them continue to be far from their native land.

The 19th century ended with the exploitation and attempted extermination of the Natives of Tierra del Fuego. Ranchers — mainly British — purposefully tried to do this, while the Salesian missions did so involuntarily. In the case of the former, in 1895, the landowners offered a pound for the ear of a dead Selk’nam, because they were attempting to hinder their wool business. The Indigenous peoples fed on the guanacos, who had been displaced by the Europeans’ sheep. When the Selk’nam tried to expel the animals, the settlers felt threatened and subsequently offered rewards to hunters, who were armed with Winchester rifles. The most lethal was Alexander McLennan, a Scotsman who said he killed 450 Selk’nam in one year.

The Salesians, for their part, established a mission in 1889 on Dawson Island. In addition to being spiritually colonized, forcibly kept under strict discipline and having their diet altered, the Indigenous people were infected with diseases brought from the Old Continent, especially tuberculosis and measles. “Dawson Island became a kind of prison for the Selk’nam, a people who had been nomadic for thousands of years. The mission cemetery — with more than 1,000 Indigenous graves — is a silent testimony to this catastrophe. In the outlying districts, the dead were simply left in the nearest bushes. Many of the sick certainly saw foxes come out of the woods and devour the corpses… but no one could defend themselves or scare them away,” Marín writes in his text.

Government responsibility

What did the Chilean government of the time have to do with all of this? “It was complicit, in that it remained silent,” the researcher answers. To begin with, all the killings and humiliations took place when Chile had already achieved its independence and autonomy in 1818. Then, it was the government of President José Manuel Balmaceda that granted a free territorial concession to the Catholic Church. Furthermore, in the 20th century — from the highest levels of government — this inferiorization of the Fuegians was perpetuated, particularly with the 1940 case involving Lautaro Edén Wellington (Terwa Koyo was his original name). He was a child who, at 10 years of age, was forcibly taken by the Chilean Air Force from the community of Puerto Edén to the capital of Santiago. The purpose was that he would be taught at the School of Specialties. Once educated, he would be returned to his community to “civilize” what remained of his ethnic group.

It’s also true that, in 1890, Chilean diplomats managed to repatriate the Selk’nam captured by Maitre, the Belgian slave trader. Similarly, at the beginning of October of this year, Chile’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs arranged for the Lübeck Museums to release the skull of a Selk’nam man to a delegation from Tierra del Fuego, who asked that it be buried in a Berlin cemetery.

The “Onas” — as 19th-century anthropologists called them — were believed to be extinct. However, in 2023, the Chilean state recognized them again. According to the 2017 census, there are 1,144 people who self-identify as Selk’nam. In 1880, there were 3,500, according to Marín’s research. As for the Yaghan, there are 1,600 people left, while two centuries ago, there were 2,500.

Marín’s publication doesn’t provide data on the Kawésqar peoples, but it’s estimated that there are now only 250. They only speak Spanish. “It’s an open wound. A slow restoration of rights,” Marín admits. A long road to finally put the bones to rest.

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.