In a museum, the Netherlands reflects on its colonial past and recognizes that it has progressed because of slavery

For the past 70 years, descendants of African communities in former Dutch colonies in South America and the Caribbean have been asking for a space that breaks historical silence. They want it recognized that their identity predates the country’s slave trade

The National Museum of Slavery, a long-awaited project by descendants of African communities from the Netherlands’ former colonies in Suriname (South America) and the Netherlands Antilles (the Caribbean), is finally taking shape. With funds provided by the federal government and the Amsterdam City Council, the new center aims to show that the Dutch slave trade — which took place between the 17th and 19th centuries — was decisive in the economic and social development of the country.

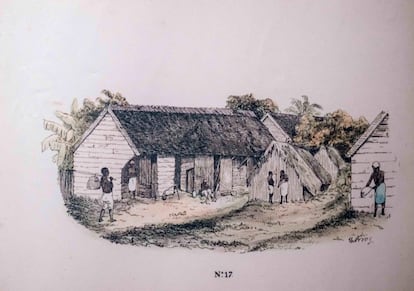

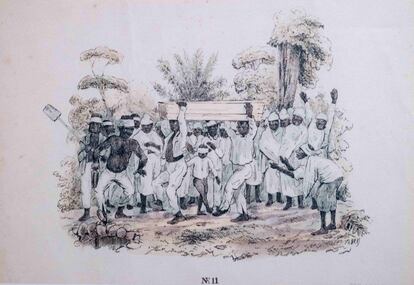

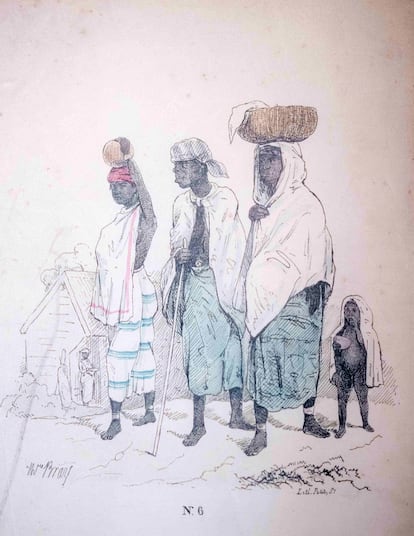

Conceived as a permanent space, the museum’s design was presented this past February. The exhibits will highlight that the history and identity of the captured peoples began long before the arrival of slave ships. After decades of requests, the opening is scheduled for 2030.

“We’ve been fighting for this museum for 70 years. Slavery must be addressed to be able to move forward together as a nation,” says John Leerdam, a former legislator from the Social Democratic Party, in a phone interview with EL PAÍS. He’s one of the three experts who have conceptualized this project.

Over the course of seven decades, the voice of African communities from the Caribbean and Suriname — many of whose members live on Dutch soil — has been heard incessantly in the Netherlands, asking for such an institution. “Keep in mind that the six Caribbean islands where your ancestors suffered are, today, part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands,” Leerdam notes. “Colonialism continues to mark the relationship between both parties in a particular way.” He’s referring to Curaçao and Saint Martin — which have the status of independent countries, like Aruba — and to Bonaire, Saint Eustatius and Saba, which are considered to be special Dutch municipalities.

Peggy Brandon, an expert in education and museology, is part of the trio responsible for the museum plan. She assures EL PAÍS that the descendants of slaves “didn’t have the feeling of belonging to a country that is truly theirs.” They’ve been asking for recognition of what happened to their ancestors since the 1950s, while organizing small, temporary exhibitions over the years.

The Amsterdam City Council gave the green light to a permanent institution in 2017. And, in 2019, the federal government joined the initiative. In 2021, the mayor, Femke Halsema, formally apologized for the role played by the Dutch capital in slavery and for the ill-gotten wealth generated from the act. Other cities have since followed suit, such as Utrech, Rotterdam, The Hague and Haarlem. Major institutions, such as the Dutch National Bank and ABN AMRO Bank, have also apologized for their historical role in slavery.

Of Surinamese origin, Brandon’s great-grandmother was the daughter of a freed slave. The museologist traveled to the Caribbean and Suriname with John Leerdam, to find out what the attitude is towards the museum in the former Dutch colonies. “In Curaçao, I found a document in the archives from 1863 (the year when the Dutch government abolished slavery) in which the slaves were informed that they were free. However, the same silence and obedience of their previous condition was expected of them.”

Brandon and Leerdam ended up speaking with a total of 5,000 people, breaking what they refer to as the “circle of silence” that still surrounds descendants of those who survived slavery. ”They wanted to know if we were part of the white man’s feelings of guilt… if we just wanted to open a museum and that’s it,” Leerdam explains.

Although the push by descendants hailing from Indonesia — another notable Dutch colony — hasn’t been as strong, that part of the past will also be addressed in the museum. According to Brandon, one has to see “the connections between both ends of the world.” She provides a key example: money was paid by the Dutch authorities to the owners of freed slaves in the Caribbean and Suriname, to compensate them. “Those sums were extracted by force from the people of Indonesia. The average citizen of the Netherlands doesn’t know this.”

For historian Pepijn Brandon — who teaches Global History at the Vrije Universiteit (Free University) in the Dutch capital — other themes have played a role in Indonesia’s colonial memory, particularly the war crimes perpetrated by the Dutch during the Indonesian War of Independence (1945-1949). “In addition, at the end of the 19th century and in the 20th century, the abolition of slavery was used as an excuse to colonize Indonesian areas where there were still slaves,” he notes. And that has clouded the anticolonial perspective, “because the antislavery discourse was [perpetuated by] the colonizer.”

A change in perceptions

While Dutch museums have made reference to slavery in their collections, the exhibition organized in 2021 by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam set the tone for those that followed. The perception has changed over time because, in the historical debate about the 17th and 18th centuries, the slave trade was once a marginal section. In the 19th century, the prevailing morality rejected those who participated in it, but “it still wasn’t considered to have been important in economic and social development,” Brandon clarifies. The historian says that it “didn’t fit into the self-perception of a nation of traders rather than conquerors… [The Netherlands sees itself as] tolerant and liberal.” Hence, the human-trafficking and colonial plantations were presented as merely being part of a negative period of time, “as if it could be separated from all the others.”

He dates the moment of change as having taken place in 2013, with the commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in Suriname and the Caribbean. King Willem-Alexander expressed his “remorse and repentance” because 5% of the total of 12 million people subjected to the slave trade by Europeans were transported by Dutch ships across the Atlantic. A decade later, in 2023, the sovereign asked for forgiveness as head of state. In 2022, Prime Minister Mark Rutte had done the same. “Since 2013, the debate could no longer avoid the fact that slavery paid for the enrichment of the Netherlands.”

For years, there was also no mention of the direct link between the assets of many Dutch families who had shares in the two firms that dominated the colonial business: the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company. The first operated in South Africa and Asia — specifically in present-day Indonesia — and historical estimates place the number of enslaved and trafficked individuals at between 600,000 and more than a million. The latter company operated in Suriname, Brazil and the Caribbean, subduing nearly 600,000 human beings on coffee, tobacco, sugar, cotton and cocoa plantations.

Each country with a colonial past deals with it in a different way. “For the United Kingdom, for example, slavery marks a milestone in collective memory, because they focus on the glorious role of the British Empire in abolition,” Pepijn Brandon explains. He then emphasizes the reality: “In the 18th century, [the British] were the largest slave traffickers in the world.” On the other hand, Dutch history marks one key moment: 1863, the year in which the authorities abolished slavery. However, between 1863 and 1873, the freed slaves were forced to work for miserable wages so that their former masters wouldn’t lose the investment made when purchasing them.

The proposal for the National Museum of Slavery includes a 97,000-square-foot building in Amsterdam’s port district. It will present “multiple perspectives and be a place for sharing knowledge,” according to Peggy Brandon, who will oversee the museum’s content. The objects on display will be from the era of slavery, while there will also be pieces made by contemporary artists who are members of the diaspora. “What’s exhibited will be viewed as art,” she affirms, “not simply [objects] from an ethnographic point of view.”

“There’s a lot of interest,” Leerdam points out. “We’ve been inspired by the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.,” the former legislator adds.

“A part of the Dutch population has an unrealistic view of the past. They believe that this type of information damages the national image,” says the historian. All three experts agree, however, that the official commitment to the museum is firm.

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.