Marilyn Cote’s patients: ‘When I refused to take her medication, she told me I was stupid and that I was going to take my own life’

The fake psychiatrist diagnosed two young women suffering from anxiety as schizophrenic and with ‘narcissistic personality disorder.’ She pressured them to take antipsychotics that she prescribed with false ID cards

Marilyn Cote has become a meme. Videos of her inventing languages and photoshopped images posing as an FBI agent or a taekwondo expert have flooded social media in Mexico. But behind the jokes lies the story of a lawyer who prescribed medication by passing herself off as a psychiatrist and who had the health of hundreds of patients in her hands at her office in Puebla. Alitzel García was 26 years old and had been suffering from depression for months when she found Cote, through positive reviews on the Doctoralia platform. Regina, then 19 years old, also trusted the website, and was desperate to seek treatment for anxiety. The former was subsequently diagnosed with “a narcissistic personality disorder” and the latter, with schizophrenia. Cote prescribed antidepressants and antipsychotics to both of them, which she signed with a false ID. Both patients spoke to EL PAÍS about the risks of being a patient of Marilyn Cote’s.

Cote’s first office was in downtown Puebla. On a small street in the Azcarate neighborhood, she received patients in a run-down building with large windows, where other doctors also worked. The psychologist saw patients in her office, painted blue and with wooden doors, with a stethoscope hanging around her neck. At the beginning she was always “friendly,” her patients say. “She tried very hard to please,” says Alitzel. “She spoke with great self-confidence,” says Regina, “she told me that she had gotten through very difficult cases. When I arrived I was desperate, confused, I had daily panic attacks, it was something I’d never suffered before and I was very worried. She seemed to have a lot of experience, a lot of credentials, and I thought: maybe she can help me.”

It was September 2019 and Regina had typed “cognitive behavioural therapy in Puebla” and “psychologist specialising in anxiety” into Google. The first search results took her to Cote. Then she checked the reviews — all positive still — and the Doctoralia page, where she had won an award as a specialist in 2017. Alitzel searched directly on the same website: “I was in a very complicated moment. Very sad, very anxious. I felt lost, I couldn’t sleep. And she was the first result that came up.” Back then, the young women say, the implausible collages that have become famous now, and the glossy ads, did not exist. “When you met her, she didn’t behave in this crazy way,” Regina sums up.

Sessions cost around 1,000 pesos (around $50) and varied in length: sometimes 20 minutes, other times an hour. “If I asked her, she would tell me: ‘My work as an expert is worth the same, I decide how long the therapies last,’” explains Regina, who remembers that Cote always made her wait before seeing her, to arrive under the pretext that she had just returned from an appointment with the Prosecutor’s Office, a conference in the United States, or attending to a patient in crisis.

The cases of the two women differ in speed, although both arrived at Cote’s office at the same time. For Regina, who was in her first year of a marketing degree at the University of Puebla, it took four sessions before a medication was suggested. The young woman was in a “very stressful” relationship and had so much anxiety that she became “really scared.” “At first she told me that she wanted to get to know me better before prescribing anything to me,” she says. “She did suggest the idea that I had narcissistic traits. I didn’t take it the wrong way, because I was very open to getting better, to being told the truth, and I thought she was the expert.”

At the fourth session, Cote explained to her that after “an exhaustive analysis” of her profile and body language, she had concluded Regina had schizophrenia. Although the young woman had never experienced hallucinations or any previous symptoms, the psychologist explained to her that “it was a matter of time,” so she had to start taking medication urgently if she did not want things to get worse. “I was shocked. I said to her: ‘It’s something serious, are you sure?’ She told me that my distrust of my partner was paranoid delusions and that my eye movements were a telltale sign of schizophrenia, that she had worked as an expert in renowned psychiatric hospitals and that she was sure.”

The diagnosis that was given to Regina, to which this newspaper has had access, reads: “She has very poor self-acceptance that can lead her to be manipulated by others or by what is established systemically. This refers to a lack of inner strength. Her sense of proportion to see what is relevant within the complex is very low. When her sense of reality fails, she lives within a fantasy. She experiences high levels of anxiety that with psychological help can be reduced or increased to tighten the field of action and move her towards a more proactive behavior. Conclusion: Schizotypal Personality Disorder with Obsessive-Compulsive traits. Traits also: paranoid, schizoid, and narcissistic. Disorder of emotional life that reduces the expression and quality of social relationships; almost autistic.”

Cote prescribed the antidepressant venlafaxine and two antipsychotics: risperidone and quetiapine. Regina bought them at the pharmacy without any problems, but she didn’t dare to take them. Confused, she went to ask for a second opinion from a psychiatrist at the Los Angeles Hospital, who neither confirmed nor denied the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Despite her doubts, Regina continued to go to appointments at Cote’s office. “Since I was not taking her medication, she tried to scare me: she told me that I was stupid, that I did not understand reason, that she had seen how patients who refused to take medication killed themselves, and she told me that this was going to be my case. ‘You are going to have visual and auditory hallucinations, you are going to lose touch with reality, and you are going to attempt to take your own life.’”

The young woman was “terrified.” “I thought, ‘I don’t want to die, I don’t want to lose control of my will and my actions.’ And I knew that I didn’t want to take my own life, but she told me that as if it were a definitive thing,” she explains. “She became aggressive, saying that she was an eminent expert, that how dare I question her, that she could profile dangerous criminals, that I was an immature girl and that my narcissism didn’t allow me to see reality.” After six sessions, and thanks to the advice of a friend, Regina stopped seeing Cote. She never took the medication. Out of fear that she would persecute her — “she told me that she worked with the Puebla Prosecutor’s Office and that she had influential contacts” — she even changed her cell phone number so that people would stop calling her from Cote’s clinic. In 2020, she gathered the courage to present her case at the High Court in Puebla, where it was rejected: “They told me that I was going there of my own free will, that I should change psychologists, and that was it.”

Side effects of medication

Alitzel García’s case was much quicker. Cote told her that she had “a depression triggered by a narcissistic personality” and from the first session she prescribed an antidepressant, duloxetine, alprazolam for anxiety and quetiapine, an antipsychotic. “She gave me the medical samples for the initial treatment and then recommended that I go to the pharmacy that was right around the corner from her office, where they supplied me with everything without any problem,” says the patient. “She told me to stay calm, that she was a neuropsychologist and could prescribe it.”

She was told to take the medication every day. “I never got better. The only thing that relatively improved was the insomnia,” García recalls. “She kept changing my antipsychotic for others, because I wasn’t getting better, but my anxiety was increasing. I had lots of side effects: tremors, more anxiety, I couldn’t stay still.” She spent almost eight months in Cote’s office and the end was marked by fear: “As I didn’t get better, she told me: ‘If your anxiety doesn’t go away, I’m going to prescribe you an injectable antipsychotic.’ I said no and stopped going.”

Both women found psychologists and psychiatrists who refuted Cote’s diagnoses and helped them with their anxiety. Both also investigated Cote and found traces of her deception, such as her fake IDs and her set-ups. Two years ago, Alitzel saw an advertisement for the fake psychiatrist again and that’s when she decided to write a review about her on Google: “She kept me on high doses of antipsychotics without any improvement. I had many adverse effects. The doctor may have many qualifications, but she is usurping the functions of a psychiatrist. I believed in her and spent an untold amount of money on consultations and medications.”

The lawyer’s aggressive response still remains with her today: “Have you got the balls to stand in front of me, Marilyn Cote, and repeat the string of defamations you are saying. You don’t have the courage. As the narcissist that you are, you are full of fear, insecurity and frustration. After two years, almost three, you are still bothering me.”

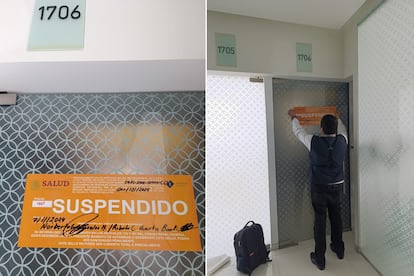

Cote’s office has been closed by the Puebla Health Department’s Directorate of Protection against Health Risks and the state secretariat has given her an ultimatum to prove that she is a doctor, before imposing more sanctions on her or arresting her. Both Regina and Alitzel agree: “It’s good that this is coming to light.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.