The finest political hour of Sócrates, one of the most unique footballers Brazil ever produced

The soccer player, who died in 2011, was one of the protagonists of the Diretas Já campaign 40 years ago to restore democracy after the dictatorship

Four decades ago, in April 1984, the streets of Brazil were crying out for freedom. The dictatorship was in its death throes. The military junta had promised what it described as a slow, gradual, and safe opening to democracy, but the citizenry was in a hurry. The people wanted direct presidential elections and staged a huge protest — the Diretas Já campaign — that provided Sócrates, one of the most unique footballers Brazil has ever produced, with the great political moment of his life. His father, a civil servant and an avid reader of Greek philosophy, chose the name. But, for the avoidance of doubt, he added a middle name before the two compound surnames common in Brazil. Sócrates Brasileiro Sampaio de Souza Vieira de Oliveira (1954-2011) went on to become a genius of a player, charismatic and politically involved like few others then or since. As of 2022, along with the Ballon d’Or, the sport’s highest individual honor, the Socrates Award has been presented to players to mark their work in social causes.

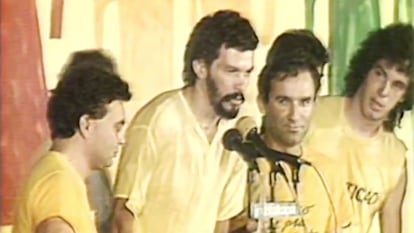

Trained as a doctor, he was nicknamed “Doutor Sócrates.” He never won a World Cup, but few doubt that he would be included in the Canarinha’s ideal 11. A Corinthians star, the midfielder co-founded a team management experiment called Democracia Corinthiana in the 1980s and acquired a progressive political awareness that brought him to the forefront of the struggle for democracy at the end of the dictatorship. On April 16, 1984, he was, with some Corinthians teammates, one of the protagonists of the largest Diretas Já rally. Among the politicians who took part was Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who is in his third term of office and was just starting to make his mark. A Corinthians fan, the Brazilian president often talks about the team he loves.

On that day, São Paulo witnessed the largest of the campaign’s mass protests calling on the generals to directly elect the first president after the military regime. Marches had already been held in Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, and other cities.

In the heat of the rally, the leftist Sócrates made a promise on stage. Dressed in a yellow T-shirt — a color that at the time symbolized democracy and not Bolsonarism as it does today — he proclaimed that, if the parliamentary amendment that would allow direct elections for president were to prosper, he would reject an offer to play in Italy. He pledged to stay home to participate, as one more citizen, in the transition. “I suspect he decided right there at the rally, seeing everyone so excited,” journalist Andrew Downey, author of Doctor Socrates: Footballer, Philosopher, Legend, explains over the phone from Edinburgh. “He was one of the few players who put principles and life ahead of money. He was willing to give up millions for playing in Italy to take part in the transition to democracy.”

Sócrates, a technically exquisite player, had a magic back-heel touch, a brother named Sophocles and another named Sosthenes. His participation in the 1982 World Cup in Spain went down in history. At 1.92m tall, his feet, on the other hand, were small: a size 8. His physique was by no means the only thing unique about him. “His father read Plato and the name he gave him illustrates how much he valued education,” says Downey, who was a correspondent in Brazil.

Sócrates made his professional debut without abandoning his medical studies, which he completed years later. And he always liked to party. He frequented bars and nightclubs. He combined his soccer career with smoking and liters of beer. Cirrhosis killed him at the age of 57.

He loved soccer as fun, considering it a job, because his horizons stretched far beyond the ball. It is often mentioned that witnessing his father burning some supposedly banned books in 1964, the year of the coup d’état, when he was 10, marked him deeply. It sowed in Sócrates the seeds of pro-democracy activism. The youngest of the family, Rai, followed in his footsteps as a professional footballer.

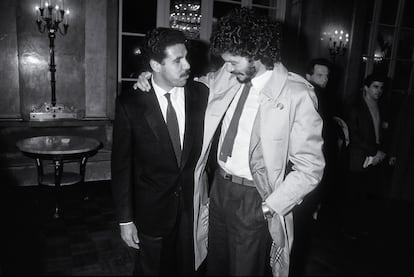

Days after the Diretas Já rally in São Paulo, Sócrates gave a wide-ranging interview: “I want to stay in my country to participate in the reconstruction. Whether it is working as a soccer player, sweeper, plumber, or doctor is another conversation”, he told journalist Juca Kfouri, from the sports magazine Placar.

Democracia Corinthiana was an experiment in collective management that the club implemented between 1982 and 1984, while Brazil was still a dictatorship. Among its promoters were Sócrates, Wladimir, and Casagrande, together with several team officials. Players, coaches, and all employees agreed to make internal decisions by means of a vote in which everyone’s vote counted equally. No other major club has ever taken such an experiment so far, and it resulted in victories on the field.

The democratic yearnings of the Brazilian people were curbed in Congress. The amendment for direct elections failed so Sócrates left to play in Europe, at Fiorentina. He once said he wanted to play in Italy so he could read Antonio Gramsci in Italian. After a single season in Serie A, he was back in Brazil. Downey maintains that, in that impromptu promise, a personal factor also played a role: “Socrates had an affair with a singer and knew that, if he went to Italy, he would stay with her. And if he stayed, he would save his marriage.”

Once he had retired, Sócrates coached, co-wrote a book, acted in a soap opera, produced a play, and recorded an album, before his untimely death. He left a deep mark on Brazil, where 1,899 people are named after him, most of them born in the 1980s, his most glorious years. Emulating his father, although in a totally different register, the youngest of his six offspring was named Fidel Castro.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.