How a small city in the Amazon reveals the strength of the far-right in Brazil

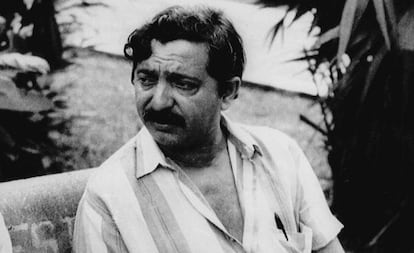

Darci Alves Pereira is an insurrectionist and murderer of the environmentalist Chico Mendes in 1988, but he has taken over local politics in the Amazonian town of Medicilandia

On February 25, a crowd of supporters gathered in São Paulo to tout former president Jair Bolsonaro, who is under investigation for his involvement in a failed coup d’état. The rally aimed to show that Bolsonaro still holds significant sway over many Brazilians. Clearly he does. However, to truly understand Bolsonaro’s influence, we need to look beyond the major cities of the southeast and focus on smaller communities like Medicilandia, a city of 27,000 along the Trans-Amazon highway. This is where Darci Alves Pereira, known for the murder of environmentalist Chico Mendes, now lives and continues to support Bolsonaro.

Now known as “Pastor Daniel,” the confessed perpetrator of a murder that shocked the world was appointed local president of the Liberal Party in January. The man who killed the defender of the Amazon in 1988 with a shotgun blast to the chest, later became president of Bolsonaro’s party. But when press reports exposed him as a murderer, Alves was dismissed. Now he’s running for a position on the Medicilandia city council, clearly showing the enduring grip of Bolsonaro’s party and ideology.

What we now know as Bolsonarism existed long before the man, but lacked a defining name and figure to unify it. Bolsonaro played a crucial role in solidifying the extreme right’s fascist ideology. In the Amazon region, which spans nine Brazilian states and over half of its territory, this mindset rules elections and daily life.

Chico Mendes was a hero to the international community, but to a significant portion of the Amazon’s population — mainly people from other states profiting from jungle exploitation — he was viewed as a nuisance to be eliminated. His killer says what he did was a “service,” and some deemed it “legitimate.” The people who live in the Amazon region see themselves as “pioneers” and “good citizens” working for progress. In many Amazon cities, local governments are controlled by land thieves, loggers and operators of illegal mines who also own many local businesses.

With Brazil’s re-democratization and the 1988 Constitution recognizing indigenous rights, these “pioneers” were increasingly viewed as negative influences and their power was curtailed. Then came Bolsonaro, who expanded their influence and power way beyond legal boundaries. The power shift and impact of this newfound “freedom” won’t be easily reversed, and may endure indefinitely.

Religious redemption was still absent, as the Catholic Church in the Amazon was connected to Liberation Theology and its leftist ideals. Many leaders of the left were trained in ecclesiastical communities. The rise of evangelical churches, now a strong support base for Bolsonaro, added another dimension. This is evident in the preaching of “Pastor Daniel” — Chico Mendes’ killer — who shamelessly invokes the name of God to justify everything.

The murderer’s choice of this Amazon city to launch his comeback tour is astonishing, but fitting. Medicilandia is named after Emílio Garrastazu Médici, a general and president known for the most severe human rights violations of the Brazilian dictatorship, including the destruction of thousands of acres of Amazon jungle. This city is now indelibly associated with Bolsonaro, Bolsonarism and “Pastor Daniel.” It’s an identity that is sure to outlive Bolsonaro himself.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.