The mysterious impact of microplastics on health: ‘The long-term effects are unknown’

Scientists have observed these tiny particles in the intestine, in the liver… and even in the brain. Experts have evidence that microplastics can cause DNA damage

The world is infested with plastics, which are crammed with materials containing more than 10,000 chemicals, including carcinogens and endocrine disruptors (compounds capable of mimicking the effects of the body’s hormones and affecting health).

Plastics are everywhere. They’ve entered the food chain. And, in the form of tiny particles — micro or nanoplastics, depending on their size — these compounds have even been identified inside the human liver, kidneys, intestines and brain. They’re presumed to be harmful… but the scientific community still doesn’t know the true health impact of these tiny materials that populate our bodies. Experts do have evidence, however, that they cause damage to cellular DNA. And they suspect that microplastics and nanoplastics can trigger numerous ailments, from inflammation to cardiovascular disease.

The plague of plastics on the planet is made clear by statistics: there are six billion tons scattered across the globe. And the number is growing. In 2019, 353 million tons of plastic waste were produced, with this annual figure expected to triple to over one billion by 2060. But all this debris doesn’t just sit in a landfill, isolated from the world. These polymers break down into smaller fragments — microplastics are tiny pieces, less than five millimeters in size — and spread unchecked, everywhere. They’re in the oceans, the air, and the food supply. And they reach humans, too: we inhale and eat microplastics, which enter our bloodstream and spread throughout our guts.

Science is working hard to understand what implications this has for health. But it’s not easy, warns Emma Calikanzaros, an environmental epidemiologist at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal): “All studies involving microplastics must be interpreted with caution, because there’s much debate about the quality of the methods and the reliability of the results. The big challenge is cross-contamination: when you have a tissue sample in which you find microplastics, it’s not clear whether those particles come from the human body, or from tools used in the laboratory to collect the samples. Microplastics are everywhere; [they’re] in the air… and also in the laboratory.”

The researcher urges caution in interpreting the data — including when it comes from some of the research mentioned in this report — and offers a warning: “Toxicity associated with microplastics has been observed in animal models and cell cultures, but we don’t have clear evidence for human health. We don’t know how [microplastics] affect [human] health in the long-term.”

Along the same lines, Ethel Eljarrat, director of the Institute for Environmental Diagnosis and Water Studies (IDAEA-CSIC), points out that microplastics are not a homogeneous whole. “They’re nothing more than small pieces of plastic which are, in turn, made up of various types of polymers to which different chemical compounds are added… some of which are toxic to health. The toxicity of the microplastic will be determined by the type of polymer [and] the type of additive it contains. [It] will also depend on its shape and size.” The smaller it is (nanoplastics are even smaller than microplastics) the greater its ability to cross cell membranes and penetrate all layers of the body.

A “plastic spoon” in the brain

A few months ago, research published in Nature Medicine warned that the concentrations of microplastics found in human tissue were seven to 30 times higher in brain samples than those observed in the liver or kidney. In practice, what was found in the brain (about seven grams) was something like having the equivalent of “a plastic spoon” in the seat of reasoning. Researcher Ma-Li Wong explained this a couple of weeks ago, in an editorial for the journal Brain Medicine: “The blood-brain barrier (a membrane that regulates the passage of molecules from the bloodstream to brain tissue) — long considered a sacred anatomical line of defense — has been crossed. Now we have [synthetic] polymers [in the same place] where cognition occurs.”

The scientists who published the article in Nature Medicine not only discovered the presence of microplastics in the brain, but also found that the brains of people with dementia had many more microplastics than those of healthy individuals. That being said, the authors admitted that they didn’t know if this was because the blood-brain barrier of the patients had become more porous, hence allowing more synthetic compounds to enter.

Eljarrat is cautious about the conclusions that can be drawn from this type of research. She emphasizes that detection techniques are heterogeneous, can provide diverse information, and aren’t yet capable of making comparisons between studies, or between the organs where there are more or fewer microplastics. “What we do know so far is that microplastics enter our bodies, but we don’t know what effects they’re having on us and at what doses. In any case, it’s not normal for there to be pieces of plastic in our brains… as a precautionary principle, we shouldn’t let it get worse,” she concludes.

The scientific literature is already peppered with cases, findings, and links regarding the impact of microplastics on health. But the evidence — as a whole — is limited, according to all those consulted by EL PAÍS. Plastic microparticles have been found in various human tissues and organs, such as blood, lungs, placentas and breast milk. They’ve also been found in the liver, kidneys, and intestines.

Another study by scientists from the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) in 2022 revealed that the ingestion of microplastics alters the balance of the gut microbiome, the ecosystem of microorganisms that inhabit the digestive tract. Specifically, the researchers discovered that the ingestion of microplastics reduces bacterial diversity and decreases the number of bacteria with positive health effects, while increasing the presence of other pathogenic microbial families.

Scientists suspect there’s a kind of bridge between diet, pollution, and disease. Not surprisingly, a recent study led by Eljarrat analyzed the presence of plastic-associated additives in foods that are commonly found in the Spanish diet. She and her team found that 85% of the 109 samples evaluated contained one of these additives (although the average intake levels found were lower than the maximum amounts recommended by health authorities). To detect the transmission of plasticizers during cooking, the authors also analyzed packaged meals and discovered that cooking processes increase exposure to these compounds up to 50-fold.

Another question raised by the discovery of microplastics in feces is the body’s ability to eliminate these materials more or less effectively. They’ve been found in fecal samples, urine, and sweat, which means they’re excreted. But scientists don’t know how much of the microplastic enters and exits the body, nor whether it still causes harm along the way. “We don’t know how much we eliminate and if what remains inside us is the most dangerous. There are contaminants that can become toxic even if we metabolize and eliminate them. Bisphenol A doesn’t accumulate in the body, but its [journey through the body] is toxic,” Eljarrat notes.

Signs of toxicity

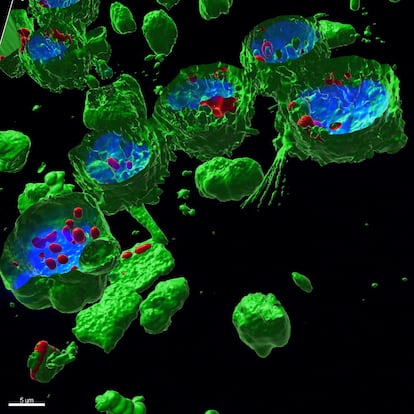

Science isn’t yet able to accurately define the footprint that microplastics leave in the body, but there are already signs of toxicity. This is according to Alba Hernández, a professor in the Department of Genetics and Microbiology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB). She’s the principal researcher with the PlasticHeal project, a European initiative focused on deciphering the impact of microplastics on human health: “We’ve seen some signs that things are happening at the molecular level in cells when they’re exposed to microplastics,” the scientist explains. The research studied workers exposed to the plastics industry (recycling, textiles, etc.) and also analyzed animal and cellular models in vitro.

In these laboratory samples, she continues, they found toxicity parameters that underpin the potential health risk. “We see that [microplastics and nanoplastics] are capable of damaging cell DNA. [Because of these particles], changes occur in the way cells regulate genes. And when cells are exposed to low doses for a long time, which is what we assume can happen to people, they begin to show signs of cancer cell transformation. We’ve also seen dysregulation of the inflammatory system and the microbiome: there’s oxidative damage,” the scientist explains. All of this, Hernández notes, could lead to immunological, gastrointestinal, fertility, fetal health, or cancer-related problems.

Experts suspect that the dose will be key to determining the potential damage. The problem is that they still don’t know how to accurately measure how much microplastic is actually in the body and what the harmful amount is. “We don’t have a clear safety limit,” the UAB researcher points out.

Synergies with other contaminants

Another thing that worries experts — in addition to the complexity in detection and the potential risk of these synthetic particles — is the synergies of these microplastics with other contaminants, such as the chemical substances that accompany these polymers, or the ones that we’re exposed to in the environment. “I think of tobacco smoke, heavy metals... that co-exposure, when [the compounds] act together. The plastic aggravates the effects of these contaminants,” Hernández points out. The hypothesis is that plastics alone, per se, don’t produce a clear effect on a disease, but together with other elements, they spur the onset of some illnesses.

Eljarrat points out that “each microplastic is unique.” There are studies that suggest that the toxicity of these polymers will be determined by the chemical compounds they carry. “We shouldn’t be [paranoid], but it’s not normal for us to have microplastics circulating in our blood. Considering the initial signs, measures must be taken to reduce these pollutants,” she argues.

Researchers are studying how to eliminate them from the air, while strategies such as therapeutic apheresis — blood-processing methods used to treat various conditions — have been proposed. But the experts consulted by EL PAÍS maintain that, for now, the most reliable method is prevention. This can be done, for instance, by avoiding the consumption of ultra-processed foods, not heating plastic containers in the microwave, and refraining from drinking bottled water.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.