Ocean plastics pollution: ‘I wish it was all packed into one big island’

An analysis of the huge floating island of garbage in the Pacific Ocean reveals that it mostly comes from five countries, but experts warn other environments like the Sea of Japan and the Mediterranean are similarly affected

Plastic – it’s a human success story. Highly functional and easy to mold, the world has produced 9.5 billion tons of plastic since 1950, when widespread use began. It’s an enormous quantity, equivalent to one ton for every person alive today. Yet only 9% of all the plastic ever produced has been recycled, and poor waste management has led to eight million tons of plastic ending up in rivers, along coastlines and in the open ocean.

The planet has struggled to cope with the plastic that permeates every ecosystem. Polymers used in clothing have been found in the digestive tracts of creatures that live in the deepest oceanic gorge on Earth – the Mariana Trench. Only three people have ever been to the bottom, 36,000 feet (11,000 meters) beneath the surface. This death-by-plastic-success scenario is what led the United Nations to prioritize the fight against marine pollution. Although attaining political consensus has been slow, irrefutable evidence of marine pollution has sparked many initiatives seeking to reverse the trend, especially in the seas between California and Hawaii where the “North Pacific Garbage Patch” floats noxiously on the ocean.

A recent article in Nature reports on a study led by oceanographer Laurent Lebreton that analyzed the origin and composition of 6,000 samples of garbage (1,100 pounds or 500 kilos) taken from the North Pacific. A team from the Netherlands-based Ocean Cleanup organization found that five countries produced most of the waste: Japan, Taiwan, the United States, South Korea and China (including Hong Kong). Moreover, up to 86% of the large pieces of floating plastic in the garbage patch were items that were lost or discarded by fishing vessels. Some of the objects in the sample were more than 60 years old. The very long lifespan of plastic is another indicator that the world is in the Anthropocene geological epoch – the era of significant human impact on the earth’s geology and ecosystems.

But all the ocean plastics pollution does not accumulate in compact masses. This is a big problem for marine biologist Andrés Cózar, from the University of Cádiz (Spain), because except for a few soupy accumulations of plastic in patches or islands, the tons of waste are scattered all over the ocean, making it hard to detect. Cózar says that study published in Nature aligns with other research findings, although he explains why it’s logical that objects found in the open ocean either come from fishing vessels or are microplastics: “The large pieces of garbage that are dumped into rivers and flow into the seas are usually pushed back to the coasts by the tides.”

Lebreton’s study describes how plastic accumulates in three different environments: littoral accumulation via rivers; coastal accumulation of large debris 650 feet (200 meters) above sea level; and open ocean accumulation on the surface and at depth. Letters and logos on larger plastic objects more commonly found in rivers and coastlines enabled the research team to identify their origins. But microplastics (smaller than 0.2 inches or 0.5 centimeters) are much more prevalent in marine currents since they flow easily once wave action breaks them into tiny pieces.

Andrés Cózar is an expert on plastics in marine ecosystems and director of the Marine Littler Lab (MALUCA) at the University of Cádiz. In 2021, his team published a paper in Nature with the results of their analysis of more than 12 million pieces of marine debris. “The North Pacific Garbage Patch is not unique. There are similar accumulations of garbage in the Sea of Japan and the Mediterranean from non-industrialized developing economies, as well as waste that doesn’t come from fishing activity.”

Aimlessly drifting ghost nets lost by fishing vessels trap and kill marine life, as do microplastics that end up in their digestive tracts. “We recently found an animal with more than 11 pounds (5 kilos) of plastic inside. Since plastic objects are often coated with zooplankton, they mistake them for food, but they’re lethal,” said Marga Rivas, a marine ecologist with the Institute of Marine Research at the University of Cádiz. Rivas is a specialist in sea turtles and cetaceans with a research focus on the effects of plastic on vertebrates. Since microplastics are too small to have identifying marks, Rivas analyzes the composition of the polymer, usually either polypropylene or polyethylene, and then traces its origin to the industry in which it is used. She firmly believes that knowing where the garbage comes from is key to pinpointing the true source of the pollution. Echoing Andrés Cózar and other researchers, Rivas said, “The Pacific isn’t the only place affected, even though everyone views Southeast Asia as the biggest polluter on the planet. We have studied other environments like the Mediterranean, where we have a terrible problem.”

The Mediterranean Sea is Jordi Sierra’s research field. A scientist with the University of Barcelona’s (Spain) pharmacy department, Sierra studies the microplastics problem. “I wish it was all packed into one big island, but it’s not.” Sierra, who also works with the TECNATOX group to study the intersection between environment and health, says that traceability is critical to finding solutions.

“Plastic is the world’s second-most synthesized material after cement, due to its usefulness and malleability. Tons are produced every year and recycling is difficult,” said Sierra. “But even the polyester fibers in clothing cause problems because they come off in washing machines. The fibers are everywhere – in the North Pole, the rain and even our bodies. It’s the same material used in the plastic bottles we drink from.” Sierra advocates using biodegradable materials, especially in the textile sector, and banning single-use containers.

Since the fishing industry and industrialized countries are not solely to blame, Cózar says the “urgency of the problem requires implementing bans and legislative pressure.” But considering the limited resources available to him, Cózar is more interested in controlling river pollution by implementing successful models that already work. “The days of plastic straws are numbered, but we have to go to the true source of the pollution – the manufacturers.”

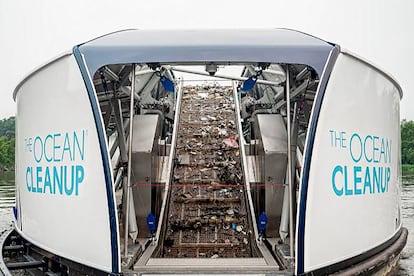

The Ocean Cleanup is a non-profit foundation based in the Netherlands that develops technology for cleaning plastic waste from bodies of water and coordinates scientific research on the subject. It was founded by Dutch inventor Boyan Slat in 2013 when he was 18 years old. After American venture capitalist Peter Thiel watched Slat’s TED talk and donated $100,000, the foundation raised more than $30 million in subsequent funding rounds. But almost a decade later, The Ocean Cleanup has not met everyone’s lofty expectations.

The foundation has developed several prototype vessels that drag nets to collect ocean garbage, as well as the Interceptor, which scoops up river garbage. But the foundation has been harshly criticized by marine biologists who say its plastics removal methods ignore tried and true models that are more cost-effective and eco-friendly. And some have accused the foundation of producing staged videos touting its cleanup efforts.

Andrés Cózar thinks that The Ocean Cleanup is doing “necessary work and is also promoting other positive measures. It has a very good PR machine that makes sure the media knows about everything they do... but as I told Boyan, I would set up projects that have already proven to be successful and profitable, such as reusing plastic bottles to make garbage barriers. I would also focus much more on the source of the problem – the rivers.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.