The forgotten report that slammed Spain’s healthcare under Franco

A 1967 study by leading figure Fraser Brockington flagged up numerous shortcomings in the dictator’s public health system

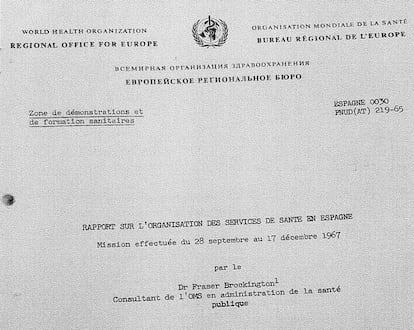

One day in 2010, a historian named Rosa Ballester was rooting around in the archives of the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, in search of old reports about poliomyelitis in Spain. Tucked inside a pile of yellowing papers, she suddenly found a 43-page document, typewritten in French and titled “Report on the organization of health services in Spain. Mission conducted between September 28 and December 17, 1967 by Dr Fraser Brockington.”

Ballester’s jaw dropped. “Nobody knew about the existence of this report,” she recalls. “Brockington invented social medicine and he was one of the great figures of 20th-century public health. And he put the spotlight on our system’s failures.”

There were so few respirators that doctors had to choose which child would live and which would die

Historian Rosa Ballester

Brockington, who had taught social and preventive medicine at Manchester University, spent nearly three months in Spain as a WHO consultant, gaining unfettered access to the departments run by Franco’s health officials. His diagnosis was a slap in the face for the dictatorship’s propaganda effort, but it is only seeing the light now, more than half a century after being drafted.

The public health specialist flagged up numerous shortcomings in his 1967 study. “Basically there is no specialized, prenatal, child protection, venereal disease or pediatric disease care available other than in provincial capitals.”

The report also underscored “the failure of the National Health School with regard to training and research in public health,” and warned of the “statistical desert” that prevented scholars from finding out the true state of healthcare in Spain. “The principles of social and preventive medicine are sorely lacking.”

His work also criticized the way Spanish doctors were stretched thin. Autobiographical notes at the archives of Manchester University show Brockington wondering with amazement how the head of the National Health School, Valentín Matilla, could have 16 additional job titles. “That was no way to work,” says the historian Esteban Rodríguez Ocaña, who found the notes.

Brockington criticized the fact that Franco had yet to create a health ministry, and that public healthcare was distributed among several departments, including the education, labor and housing ministries. This chaotic situation was having “disastrous effects,” according to Brockington. “There is no regular dialogue among the various ministries. It is a matter of the utmost urgency to resolve this situation.”

According to the historian Rodríguez Ocaña, who has just published the Spanish translation of the Brockington Report in the specialized magazine Gaceta Sanitaria, the WHO document evidences that the Spanish healthcare system at the time was “worse than those of many other developing countries.”

Rodríguez Ocaña and Ballester do acknowledge some achievements made by the Franco regime, such as the eradication of malaria and the reduction of child mortality. Before the Civil War, between 1930 and 1934, 120 children under one year of age died for every 1,000 live births, compared with 80 in France. That figure shrank progressively during the dictatorship, dropping to 70 in 1950 (52 in France) and 28 in 1970 (15 in France), according to research by the sociologist Rosa Gómez Redondo.

Many departments

Rodríguez Ocaña has dug into the origins of the organizational chaos in Spain’s healthcare system. Following the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939, the various factions within the winning side began fighting for their share of power. The Catholic military officials got the Governance Ministry and the National Directorate of Health. The Falangists were awarded the Labor Ministry and the National Provision Institute, which carried on with the social insurance program designed under the Republic.

Mandatory sickness insurance was introduced in 1942, but it left out most rural workers and the unemployed. This insurance program was described in 1944 by Labor Minister José Antonio Girón de Velasco as “enabling a worker to no longer be a poor man forced to turn to public charity and undergo the shame of being hospitalized with beggars, but to become a soldier who is assisted by his peace army’s health services when he is discharged.”

“The propaganda machine insisted that Franco invented the insurance system, but the sickness insurance law was admitted into parliament in July 1936. The Franco regime did not invent it. There was already fake news back then,” explains Rodríguez Ocaña. Following the sickness insurance, new legislation was passed in 1947 approving old age and disability insurance. Unemployment insurance came along in 1961, and these were all unified under a national social security system in 1963, as Rodríguez Ocaña explains in his book Salud pública en España. De la Edad Media al siglo XXI (or, Public Health in Spain. From the Middle Ages to the 21st century).

Other experts have also noted that Franco’s propaganda efforts did not reflect reality. “The facts do not fit in with the dictatorship’s media fixation on the health problem,” write the historian Jerònia Pons and the economist Margarita Vilar in their 2014 book El seguro de salud privado y público en España. Su análisis en perspectiva histórica, (or, Private and public health insurance in Spain, a historical perspective analysis). “The budget allocations for the General Directorate of Health as a proportion of the total national budget was practically the same between 1943 (1.05%) and 1958 (1.02%).”

During his stay in Spain, Brockington was offered an office at the General Directorate of Health in Madrid. From there he traveled to several provinces to collect first-hand information for his report. But little came of it.

“Brockington’s recommendations were left to gather dust,” says Rodríguez Ocaña. In 1936, there had been a health ministry under Federica Montseny, an anarchist who was the first female minister in any Spanish government. But the Civil War ended the experiment, and there was no Health Ministry in Spain again until 1977, two years after the dictator’s death.

Ballester, who is a researcher at Miguel Hernández University in Elche, underscores the importance of the “statistical desert” noted by Brockington. “There weren’t even any statistics. How were authorities going to act?,” she wonders. “In the case of polio, there were little children who were crippled or who were unable to breathe. When some of Spain’s bigwigs attended international conferences, they boasted about having mechanical respirators, the so-called iron lungs, in every province. But when WHO observers came along, they saw that there were so few of these devices that doctors had to choose which child would live and which would die.”

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.