When fake news ruins real lives: meet the Spaniards destroyed by online rumors

Everyday Spanish people are being hurt by false accusations – like Francisco who was wrongly blamed for a brutal robbery in a viral Facebook post

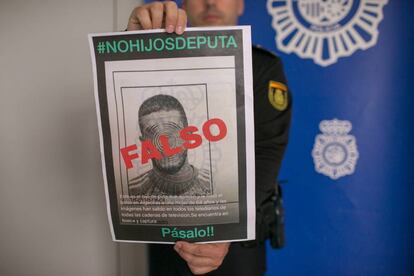

A photo accusing Francisco Canas of a brutal robbery went viral on social media this week. From Madrid to Mallorca, the image was shared thousands of times. It reached Francisco’s older brother Carlos via his workplace WhatsApp group. His mother was sent it by her friends. The message accompanying the photo was almost always the same: “This is the son of a bitch who attacked and stole the purse of a 64-year-old woman in Algeciras … The search is on to capture him. Pass this on.” At the Canas family home, all they could do was cry. They didn’t know how to stop the rumor mill.

Unfounded rumors can be punished in Spain with up to two years in prison

The video footage of the robbery is shocking. It shows a man, supposedly 21-year-old Francisco Canas, violently attacking a woman from behind as she opens a door. He punches her and knees her in the stomach until she falls to the floor, then steals her handbag and runs away. But it is impossible for Francisco to be the man in the video. On April 15, the day of the attack, he was in prison, accused of three violent robberies committed on April 7 and 8. But he has already been condemned for this one and labeled by thousands of Facebook users as a “son of a bitch.”

The police, who deal with false accusations like this every day, had to post a special message on their Twitter account to discredit the rumor.

After his photo went viral, Francisco has had trouble in jail, says his brother. “We are talking about a prison that is dangerous! He is a kid. He has received threats and they have tried to attack him,” explains Carlos.

Francisco is just the latest victim of fake news, a phenomenon – more commonly associated with election campaigns and geopolitical intrigue – that is now effecting everyday lives. From the teachers falsely accused of being child abusers in parents WhatsApp groups and forced to leave their schools, to the women who are made out to look like prostitutes after their angry exes register them on sex sites, fake news is no longer a problem that just affects the political elite.

In Spain, lies like these – which can be punished with up to two years in prison if found to be slanderous – typically do not do more than damage a person’s reputation, albeit on an enormous scale. But in other countries, online rumors can lead to public lynchings. In 2014, a housewife in Brazil was stoned to death after someone posted on social media that she looked like the computer drawing of a woman accused of kidnapping children.

When we speak about fake news we should broaden the term. Everyone is at risk Communications consultant Miguel Zorío

“Digital platforms are failing to assume their responsibility for the dissemination of lies,” says León Fernando del Canto, a lawyer who specializes in social media. “These companies don’t have legal representation in Spain and even if they do, you send them a certified fax and they don’t answer you. It is impossible for them to filter everything, but it you raise a complaint, they should put forward a solution.”

Beatriz Patiño, a lawyer specializing in new technology, says the failure of both corporations and small website owners to quickly respond to complaints is a big problem. “Sometimes they take so long to respond that the damage has become enormous and you have to go to court to ask for compensation,” she explains.

Some of the clients of Luis Gervas, the founder of salirdeinternet.com, a website which helps people delete their online footprint, do not even use Google. “Other are so traumatized by the damage an unfounded rumor has caused them that, out of fear of reviving the issue, they don’t even want to publish the court decision that shows that what was being said wasn’t true,” says Gervas. “They think no one will believe them.”

Around 44% of Spanish people receive between one and five unfounded rumors online a week, according to the latest report by communication consultancy agency Comunica Más por Menos. The report found that 31% of people believe them to be true. “When we speak about fake news we should broaden the term. Everyone is at risk,” says Miguel Zorío, the director of the agency. “These types of falsehoods have always been around, but now they are spread immediately and on a massive scale.”

A housewife in Brazil was stoned to death after someone on social media said she looked a child kidnapper

Another false accusation forced 48-year-old G.D.L. to run to a police station in Madrid after he was labeled a sexual predator. On January 25, a woman said she had been assaulted in Puerto de Santa María in Cádiz. When police officers showed her photos of possible suspects, she pointed at the one of G.D.L. This photo should have been used internally to locate the aggressor but wound up on the front page of newspapers across the region, making it all the way back to his friends and family in Romania. But G.D.L. had never been in Cádiz. Hours after the woman reported the attack, the true offender was arrested. But to this day, images of G.D.L. can still be found online with the word “rapist.”

Jennifer Alejandro Flores from Catalonia was another victim of fake news. In November, her photo was shared with a screenshot of a message, supposedly from her Facebook account. The message threatened to bomb the ship where Spanish national police were staying after being deployed to control the Catalan independence push.

The police took her in for questioning and accepted that she was not responsible for the message. But despite this, Alejandro Flores disguised herself for more than a month, wearing glasses, hats and avoiding the clothes that appeared in the photo. “I was afraid. I didn’t know who might have seen it, who had written it … With everything that is happening with the Catalan independence movement, imagine if someone recognized me,” she recalls. Like G.D.L., her image can also still be found online.

English version by Melissa Kitson.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.