Catalonia: it’s all in the head

Nobel laureate Ramón y Cajal quashed the pseudoscientific theories fueling separatism in Catalonia

On his first day as mayor of Barcelona, Dr Bartolomé Robert gave a conference to an expectant audience in Barcelona. The subject of his talk was “The Catalan Race.” The date was March 14, 1899.

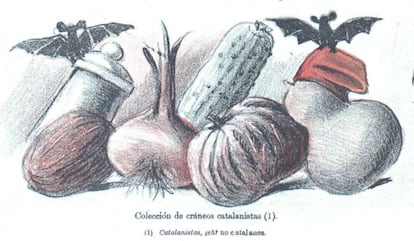

Surrounded by huge sketches of skulls, Robert began to lay out “the solid proof of the cephalic index of the various races, following their path across Spain,” according to an article that appeared the following day in La Vanguardia newspaper.

The mayor of Barcelona, Bartolomé Robert, declared the existence of a “Catalan Race” with a different cephalic index in 1899

Standing by a colored map of the country, the doctor declared that those from Valencia had a more oval shaped skull while in Asturias and Galicia there was a prevalence of rounder craniums similar to those of the “primitive inhabitants” coming to the Iberian Peninsula from North Africa.

In Catalonia, meanwhile, the shape of the skull fell somewhere between these two types, according to Robert, who described as “notable” the skulls of Aragon, “where the anthropological difference appears to be more distinct on both sides of the border.” The article added that Dr Robert would be leaving the characteristics of the Catalan race to another conference to be held at a later date.

Dr Robert’s claims sparked controversy, and attracted the attention of his former colleague, neuroscientist and Nobel Prize winner Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who spent five years as a professor at Barcelona University’s medical faculty.

In his memoirs, Recollections of My Life published in 1917, Ramón y Cajal still recalls the “genuine affection” that existed between he and Dr Robert: “An eminent doctor, champion of the precise and purposeful word who, as time passed, was to surprise those of us monitoring Catalan nationalism by proclaiming to the entire world a little insubstantially (he wasn’t an anthropologist…), the theory of the superiority of the Catalan cranium over the Spanish cranium.”

Wryly, Ramón y Cajal suggested that Robert’s opinion would be “impartial as, besides having a meager though well-furnished cranium himself, he was born in Mexico and had a French surname.”

Dr Robert had indeed been born in Tampico, the son of a Basque mother and Mexican father whose roots lay in Catalonia. In October 1899, six months after his controversial conference, Robert stood down as mayor and died three years later.

Researchers today give little importance to the racist element that historically fueled separatism. In his thesis on Dr Robert, the historian Santiago Izquierdo, from the University of Barcelona, points out: “At that time, the study of human races did not have the implications that they have today – particularly with regard to politics.” And he insists that Robert himself made it clear in 1900 that he was not talking about “privileged skulls,” although he continued to insist on the different cephalic indexes evident in the various regions of Spain.

Ramón y Cajal did, however, see it as exacerbating the drive for independence. He loved Catalonia and hated the idea of it breaking away from Spain. In his book, The World Seen at 80, published just days before he died in 1934, he bemoaned the antagonism that was surfacing in parts of the Basque Country and Catalonia. “After all that’s been said, we hope that common sense prevails in the regions that come under the Statutes, without getting to the point of violence and dismemberment that would be fatal for everyone. We are convinced of the good sense of the Catalans, although it is clear that serene and impartial attitudes are hard to achieve among people systematically poisoned by passion for 34 years or among those in the grip of secular prejudice,” he mused.

Born in Petilla de Aragón in Navarre in 1852, Ramón y Cajal chose Catalonia for his second home. His father had studied medicine in Barcelona, and he himself made his first discoveries on neurons, which he called “the butterflies of the soul,” in Barcelona between 1887 and 1892, winning him the Nobel Prize. A number of his children were also born in the Catalan capital and it was there that one of his younger daughters, Enriqueta, died tragically from meningitis.

Some years earlier, in 1873, he finished his military service in Lerida, where he had fought against the Carlists, who were trying to enforce their claim to the Spanish throne. “During these military maneuvers, I had the chance to get to know the Catalan character well,” he writes in Recollections of My Life.

Ramón y Cajal is hardly ever mentioned in Catalonia as he was very critical of separatism

Great-great nephew Santiago Ramón y Cajal

He went on to say: “In homes where they would get together, including the most humble families, the women were proud to speak Spanish, and they made every effort to make our stay pleasant. They believed that Catalan, with its homegrown dialect, was appropriate to nothing more than terms of endearment and communication within the home.” He added that “affection for Spain” arose “spontaneously in all the Catalan provinces.”

In his writings, Ramón y Cajal suggests that some of the Catalan population were later “poisoned” by prominent figures peddling pseudoscientific lies. “The rise of Catalan [separatist] politics was also reflected in attempts to establish the particularity of the Catalan physique,” writes Lluís Calvo in the Anthropological History of Catalonia, published in 1997.

Ignorance provided the perfect breeding ground for these theories, according to Calvo, director of the Institución Milà i Fontanals of the Higher Council for Scientific Research in Barcelona. “The lack of development in anthropological research in Catalonia in the 19th century, together with the scant mention of research into prehistoric issues and archeology, meant that in certain political circles in Catalonia, arguments pertaining to physicality were sought to justify the aforementioned particularity,” he writes.

It is clear that serene and impartial attitudes are hard to achieve among people systematically poisoned by passion Ramón y Cajal

Calvo also refers to the historian José Pella y Forgas, who asserts a physical difference among the Catalans in his Studies of Catalonia Ethnology published in 1889. “Our identity survives and cannot be confused with the Spanish or French due to its own basic ethnicity (evident, among other things, from the Sardinian skull, predominant in Catalonia and to a lesser extent in Valencia and Mallorca),” says Pella y Forgas.

But Antoni Rovira i Virgili, a left-leaning Catalan politician, wrote in his 1917 book Catalan Nationalism, that Dr Robert had not strayed from the realms of scientific research in his conference and had drawn no far reaching conclusions. “If a different kind of skull was prevalent in the north east of the peninsula, we Catalans aren’t going to deform our skulls for the sake of Spanish unity,” he said.

And in reference to the October 12 celebration commemorating the discovery of America, Rovira i Virgili had this to say: “Speaking about the Catalan race is not tolerated while the artificial and arrogant Fiesta of Race is celebrated in territory where the Spanish language is spoken.”

The discussion over “The Catalan Race” would appear to be a craze from another century, but it has had echoes in recent years. The historian Oriol Junqueras, the head of the Catalan Republican Left (ERC) party and who is currently languishing in jail on charges of sedition, was quoted in 2008 in the Avui newspaper, speaking about a scientific study of Europe’s genetic map. “There are three states (only three!) where it has been impossible to group the population according to one genetic group. In Italy, Germany […] and Spain, between the Spanish and the Catalans,” he said.

The rise of the politics of Catalan separatism was also reflected in attempts to establish the particularity of the Catalan physique

Historian Lluís Calvo

Junqueras perceived a genetic division that did not appear in the data. What that study in fact said was that the genetic differences were minimal across the continent with a gradual variation relating to distance. If you take samples from just two sections of the population, as was done in Spain, these minimal differences show up. “If they had analyzed more, a gradual change would have become evident. There are no genetic borders or boundaries,” says biologist Jaume Bertranpetit, from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, one of the authors involved in the study. “Genetically, Europe is very boring.”

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, a great-great nephew of Ramón y Cajal, and a prestigious pathologist at Barcelona’s university hospital, Vall d’Hebron, believes that Catalonia “ignored” his uncle despite the fact he won the Nobel Prize thanks to the work he carried out there. “Ramón y Cajal is hardly ever mentioned in Catalonia,” he says. “Because he was very critical of separatism. He was very anti-independence.”

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.