Meeting the survivors of death row

A group of people who were exonerated in the US regularly get together to share their stories

“Hi. This is my first time here. My name is Sabrina Butler and I am the only woman in the US to be exonerated. I was on death row for six-and-a-half years. I was released in 1995. I’m glad I came.” More than 50 people break into applause. Sabrina’s voice is a welcome addition to the abolition cause they are fighting for as members of Witness to Innocence, an association of people who were exonerated after being sentenced to death for crimes they didn’t commit.

They and their families meet behind closed doors twice a year. They call it “the gathering,” a spiritual retreat that lasts three to four days.

They cross the US to meet and share their nightmarish experiences and the subsequent anguish that they find hard to shake off.

Sabrina had her first child when she was 15 and her second at 17

But they also laugh and enjoy one another’s company. There is an unmistakably upbeat vibe here, perhaps because they have known and emerged from the depths of misery. It gives them a special glow, but you can also see the scars.

It’s June 2011 in Richmond, Virginia. This time the Witnesses to Innocence group have met at the Roslyn Retreat Center, an old estate belonging to the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia that invites visitors to “relax, renew and reinvigorate.”

It sits at the top of a gentle slope and is surrounded by green fields. As the sun goes down and the fireflies come out, the former prisoners get together for a barbecue with plenty of hamburgers, hot dogs and beer.

There’s a rock concert inside one of the barns. A silent type in a cowboy hat named Albert Burrell dances enthusiastically. He spent 13 years in Angola, Louisiana, one of the worst prisons in the United States.

Sabrina Butler and her mother Roszalia Ellen have come from Columbus, Mississippi. Columbus is part of America’s Bible Belt, once a stronghold of slavery and racial segregation. Sabrina had her first child when she was 15 and her second at 17.

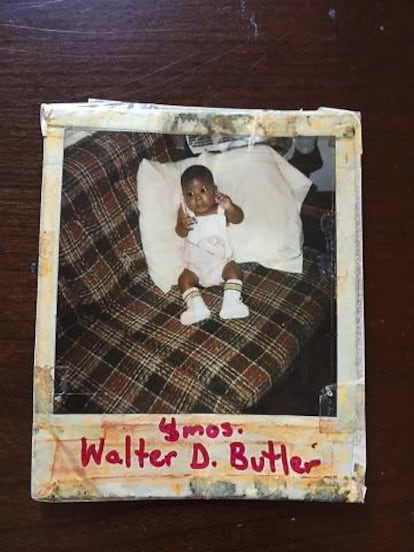

One morning in 1989, her second child stopped breathing. In a state of shock, Sabrina followed her neighbor’s advice and tried to revive her son using cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). By the time they got Walter to hospital, he was dead and his chest was bruised. Sabrina was arrested and sentenced to death. She was just 18.

June 2016. Sabrina looks out of her front door. Tucked behind an industrial estate, a gas station and a scrapyard, the house doesn’t have a great view but Sabrina is smiling and feeling positive. On the walls of her home, she has pictures of civil rights activists Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, as well as US President Barack Obama. Her first son Danny, now 30, says hello.

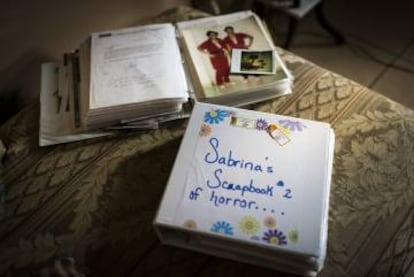

After her release, Sabrina started over. She married Joe Porter, one of the guards on death row, and had two more children – Joe Jr., 19, and Nakeria, 14. She digs out her “Scrapbook of Horror,” which is filled with newspaper cuttings about her case. It also contains an old picture of baby Walter that was stuck a thousand times to the walls of her prison cell with tape.

Sabrina is one of the few individuals to have won compensation after proving her innocence. She asks for the sum to remain confidential, but it was enough to buy two small houses – the one where she lives and another one that she rents out as her sole source of income. Since her release, she has not been able to find work.

Her former home is close by. She gets in the car and drives to the apartment where her baby died. Clive Stafford-Smith, the civil rights lawyer who agreed to handle her appeal, managed to prove during the retrial that Walter had died of a kidney disease. Stafford-Smith has since moved on to represent and secure the release of a large number of prisoners from Guantánamo Bay.

Sabrina fights a system that releases just one prisoner for every 10 who are executed

On the way, Sabrina points out the probable cause of her son’s death – a piece of land once occupied by the Kerr-Mcgee chemical plant. For years, they used the Afro-American neighborhood to dump waste from creosote – a chemical substance that can cause irritations, convulsions, kidney and liver problems and skin and scrotum cancer. People still live in the area despite the fact the land continues to be contaminated – one of 2,772 toxic locations across the country.

The company was reported in 2012 by the US Department of Justice. Two years later, they reached a deal in which the company agreed to pay $5.1 billion for the cleanup and to compensate the 8,000 people affected. Sabrina is still fighting to be recognized as one of the 8,000.

The car turns into a dead-end street. An apartment block looms. Sabrina looks at it for a moment and puts the car into reverse with a sigh. “I don’t like being here,” she says as we leave. We drive off and her mood lifts as she recalls her first meeting at Witness to Innocence in Virginia. “Those four days were very exciting. They made me feel good!” she says.

Her post-prison story is fairly typical. Following their release most people like Sabrina feel lost. Work is hard to find and it’s difficult to fit back into society. The first time Sabrina realized there were others like her was in 1998, when Northwestern University in Chicago set up a conference on miscarriages of justice, bringing together 63 victims of erroneous convictions, 20 of whom had been on death row.

Sabrina went along, but it took her another 13 years to make it to Witness to Innocence. Today, she fights a system that releases just one prisoner for every 10 who are executed. Since 1976, the justice system has admitted 156 miscarriages of justice in death penalty cases.

Despite what Sabrina says, there was one other woman – in 2015, Debra Milke was also exonerated and joined Witness to Innocence. Only 50 of the 156 survivors are members of this elite club – it’s not easy to find former prisoners whose sentences have been overturned. Some disappear and others want to put their pasts behind them.

Ron Keine is one of the most pro-active members of Witness to Innocence when it comes to seeking out fellow survivors – possibly because of his own story, which unraveled at the start of the 1970s. He was a biker in the Born to be Wild era and belonged to a biker gang named The Vagos, renowned for its criminal activities.

Along with three other bikers, he was convicted of a murder he didn’t commit. His trial was something of a farce with bribed witnesses and forensics and a complicit prosecution. After two years on death row in New Mexico, the date of his execution was set. Nine days before it was carried out, a policeman came forward and admitted to the crime.

That was 40 years ago and Ron prefers to focus on the positive. “When they sent me to death row, I wasn’t busted, I was saved. I would have ended up dead from a bullet or I would have killed someone in the bikers’ wars. I went to the funerals of 11 biker friends,” he says as he stands on the porch of his house in Sterling Heights, Michigan. Opposite is the garage where he keeps his Harley, along with other motorbikes he is repairing and a Chevrolet El Camino semi-convertible.

On his release in 1976, Ron kept to himself. His face was instantly recognizable from the news and he attracted his share of stares. So he buried himself in his work, putting in 18 hours a day. “I wanted to get my life back on track,” he says. And he did. He started by selling sacks of salt in winter for the ice on the roads. In less than a year, he was employing 80 people. He didn’t think for a moment that there might be others like him. “Other innocent people on death row?” he says. “I never thought about it.”

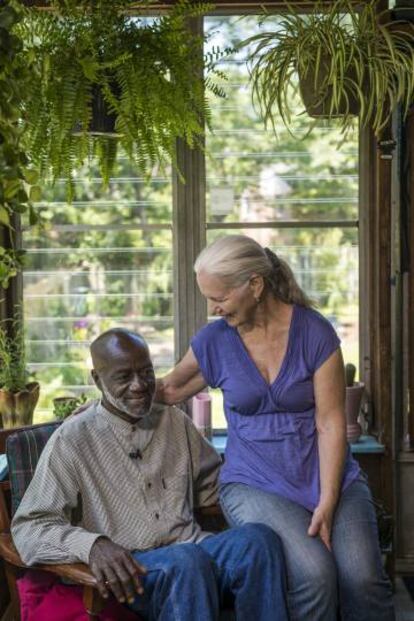

In 1998, Ron was also invited to the Northwestern University of Chicago conference but he wasn’t sure he should go. His partner Pat Aimee convinced him to. “Do it,” she said. “You’ll meet other people like yourself.” Pat and Ron started dating in 1994. It took him a while to admit to his past, but she remembers when he did. “I felt this pain in my chest,” she says. “I had so many questions. How do you survive something like that?” Be it partners, sisters or daughters, it is often women who provide the wrongly convicted with the crucial support they might not make it without.

That Northwestern University conference was the genesis of Witness to Innocence, which was set up in 2003 by anti-death penalty activist Sister Helen Prejean – played by Susan Sarandon in the movie Dead Man Walking – and by Ray Krone, the 100th person to be exonerated from death row in the US. The idea was to empower other exonerated survivors by giving them a voice they could use to lobby against the death penalty in the US.

In the mid-1990s, 80% of the US was in favor of capital punishment. Today, that figure has dropped to 61%. Since Witness to Innocence was set up, the death penalty has been abolished in eight states while four more have refrained from applying it. According to Ron, Witness to Innocence has played a key role in this shift. In 2015, there were 28 executions, the lowest number in 25 years.

Paradoxically, Amnesty International has warned of a global rise in capital punishment. Without counting China, 1,634 executions were carried out last year, 60% of them in Iran – making it the highest death toll of this nature since 1991.

Prejean, who has spent her life campaigning for the abolition of the death penalty in the US, explains the importance of the exonerated survivors’ accounts in the struggle. “Some people have preconceived ideas about them, such as ‘they must have done something. They must have got out on a legal technicality.’ They don’t trust them. But when they hear them speak, they start to ask themselves, ‘What if this happened to my son? What if it were me?’”

In October 2011, eight exonerated survivors toured Texas giving talks, conferences and interviews, both in big cities and small rural communities; in churches and universities. It’s a road trip and they’ve christened it the Texas Freedom Tour – two weeks spreading the word in the state that has carried out a third of the 1,437 executions of the last 40 years, the most of any state in US history.

With more than 30 years behind bars between them, Ron Keine, Albert Burrell, Greg Wilhoit and Shujaa Graham are sharing a van. The banter is lively as they exchange stories. Since their first meeting in 1998, they have become close.

Shujaa, an African American who spent his childhood in the cotton fields of Louisiana, takes the podium at the law school of South Texas University and declares: “I am not alive thanks to the system, but in spite of the system!”

He gives a stirring speech, followed by one by Greg Wilhoit, which is more shocking. “My nightmare began when my wife was found brutally murdered. She had been raped, beaten and had her throat slit – you know, the works,” he explains to his audience.

Greg was the obvious suspect. He and his wife had met in rehab. They had two daughters, aged 14 months and four months, but after two years together they had decided to split up.

Greg was convicted in 1985 on a single piece of evidence – a bite mark on his wife’s chest. He spent five years on death row in Oklahoma. When his case was reopened, the bite mark was shown to belong to someone else. He was released in a matter of days and moved to Sacramento, California, where he tried to rebuild his life and even remarried. But he slipped back into drug use and started to drink – clear symptoms of post-traumatic stress. He died in 2014 from liver disease.

In spite of everything, the Wilhoit family appears to be at peace with the world. Greg’s parents, Ida Mae and Guy, live in the house they have always lived in on the outskirts of Tulsa, Oklahoma. As they sit in their living room, they explain, as Greg did when he was alive, that the worst part was giving up the two little girls for adoption. The girls do, however, still visit their biological grandparents, though Greg refused to allow them to visit him in prison.

Krissy, the eldest of the two girls, holds Guy’s hand tightly and recalls the day her father was let out of prison. “I flung myself at him and hugged him,” she remembers. Until then, she had only spoken to him on the phone. She and her sister called him Daddy Greg. The relationship was good but emotionally he wasn’t their father.

Stoically, the family go into the details of the case – the feelings of guilt and the drunken lawyer who did nothing for them – an element they did not react quickly enough to. “I hope you never have to hear a prosecutor tell you what a cruel and horrible person your son is,” says Guy. “I pray that I will one day be able to forgive that man. I haven’t been able to so far. I still hate him.”

When Greg was declared innocent at the retrial, his father said, “You have been given a second chance.” Guy adds that his son grabbed that chance with both hands and became a powerful campaigner against the death penalty. “It was amazing,” says Guy. “We had no idea he was capable of speaking like that.” Greg’s sister, Nancy, agrees. “It gave meaning to his life and raised his self-esteem,” she says. “And he met his best friends, Shujaa Graham, Ron Keine…”

Witness to Innocence was set up as a lobby organization centered on speaking events. But it was soon clear that the mutual support it gave its members was equally important. “They sat down and started to tell stories about death row with really dark humor. It was hilarious. It was an awesome vehicle. They gave new direction to the organization,” adds Guy.

The talk between survivors often happens behind closed doors. It is intense. They drink one beer after another and switch from laughter to seriousness in a matter of seconds. It is quite something to hear Ron Keine, the former biker, tell Randy Steidl who spent 17 years on death row in Illinois, how eight guards took him from his cell and beat him senseless as it grows dark on the Virginia ranch. Ron’s partner, Pat, who is sitting beside him, closes her eyes and covers her ears.

The room falls silent but then Randy recalls how one of the reporters who interviewed him when he was released, asked: “What did you miss most in prison?” He arched an eyebrow meaningfully. “Apart from that!” the reporter cried. And they all laugh.

From time to time, things go dramatically wrong for the survivors and their families. Shabaka Brown, for example, killed his wife in 2012. He had been on death row for 14 years and was a member of Witness to Innocence. Both he and his wife were alcoholics, but the news shook the organization; the therapy sessions it offers try to make sure the trauma of being on death row doesn’t lead to these kinds of situations.

During the meetings, they debate how best to campaign against the death penalty and how to get compensation. But there is also karaoke, chats into the small hours, nights out. The silent cowboy, Albert Burrell, may not know much about reading and writing but he loves to dance. He lives in Texas. In 2011, he was living in an old caravan on his sister Estell’s ranch where he kept two horses and made money from selling scrap metal.

Albert was convicted after his ex-wife falsely accused him of a local double murder. At the time, they were embroiled in a custody battle for their son. When the police arrested Albert, they promised him food and water if he signed a document declaring his guilt. Albert, who could write his name along with a handful of other words, signed. He then spent 13 years on death row. When he got out in 2000, he was given $10 and a jacket. It was snowing. He has never seen his son again.

Albert is one of the most protected members of the Witness to Innocence group. Phyllis Prentice, Shujaa’s wife who is on the management committee, compares the retreats to reunions for war veterans. They are not only important for the survivors but also for the families. It’s a place where they can share their fears.

Living with someone who has been wrongly convicted is not easy. They have nightmares and panic attacks. They have post-traumatic stress. Phyllis was a young white girl from rural Iowa when she met Shujaa in jail. She was working as a nurse at the time and also belonged to a movement that was trying to improve prison conditions. As such, she was instrumental in Shujaa’s release in 1981.

Without knowing what to expect, Shujaa and Phyllis left the prison and California behind to embark on a life together. Thirty five years later, they have three children and six grandchildren who crowd into their cozy home in Maryland where posters of Geronimo, Che Guevara and a quote from Martin Luther King adorn the walls.

It’s suppertime and noisy. The table is covered with newspaper. The family sits down to eat spicy southern-style crab dripping with butter to celebrate Father’s Day.

The children laugh as they recall the day their father told them how he met their mother. “We used to kiss between the bars,” he told them. “She used to bring me burritos to eat…”

Phyllis says it has hardly been a fairytale. What keeps them together is their political and social activism, but they have gone through tough periods, such as the time when Shujaa, without any apparent reason, stopped talking. “It didn’t change anything,” says the middle daughter Cokie. “To us, he’s a hero.” This is borne out by the tattoo of Shujaa’s face on the arm of Jabari, the youngest son.

Outside, it’s getting dark. There are fireflies flashing through the air in the back garden. It is one of the many gardens Shujaa looks after, his only job since being exonerated.

Shujaa was born on a cotton plantation in Louisiana, but his family soon moved to South Central, one of LA’s most notorious neighborhoods. This was where Martin Luther King, Malcom X and the Black Panthers waged their battles for civil rights. Shujaa was still a child when he arrived but it didn’t take him long to join a gang and start robbing cars and getting into fights.

The police arrested him for the first time when he was 15 and he spent his adolescence in and out of reformatories for young offenders. At 18, he went to prison for the first time for a theft he was “absolutely guilty” of. But once inside, he started to read, write and study. “I began to change and reject my past. I joined a movement that fought for prisoners’ rights, social justice and education,” he says. He signed up for hunger strikes and protests, earning him 15 months of solitary confinement and several prison moves.

When a guard was killed during a prison revolt in Stockton, California. Shujaa was accused of leading the riot. He was sentenced to death and taken to San Quentin. He has spent 11 years in total in prison, eight of them on death row.

Back in Maryland, the living room is rocking with energy. The TV is showing an NBA basketball game and LeBron James has just scored. One of the grandchildren brings out a fresh apple pie. It’s the perfect end to a day that started off with Jabari’s baseball game when Shujaa was on the bench as usual, shouting: “Come on, son! Fight! That’s what we’re here for! To fight!”

English version by Heather Galloway.

‘The Resurrection Club’

In 2010, El País Semanal went to Birmingham, Alabama, to attend a private meeting of exonerated death row survivors. Over four intense days, 21 people who had been sentenced to death for crimes they didn't commit told their stories. Their wives, siblings and children were also there. They all belonged to Witness to Innocence, the only organization in the US composed of and led by exonerated death row survivors and their families.

Since then, Álvaro Corcuera and Guillermo Abril, two El País Semanal reporters, and Luis Almodóvar, a cameraman from El País TV, decided to make a documentary, returning to the US from time to time to interview the members of this elite club: Pennsylvania in 2010, Virginia and Texas in 2011, Delaware in 2014, Oklahoma, Missouri, Maryland and Michigan in 2016. It has been a six-year journey focusing on Shujaa Graham, Ron Keine, Greg Wilhoit and Albert Burrell and bringing in 30 accounts from their family and friends.

Their struggle, survival and friendship are the subject of a documentary entitled The Resurrection Club, produced by La Claqueta PC with Talycual Cinema and Tito Clint Movies, and made with the backing of Amnesty International.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.