Why do the Spanish “shit in the sea”?

New book explores the origins of puzzling Spanish idioms that sound shocking to outsiders

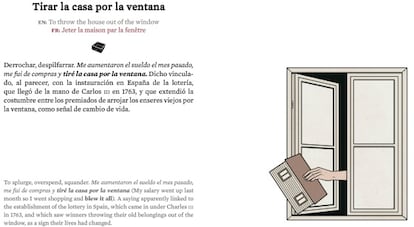

Spaniards use them on a daily basis, but often don’t know the first thing about their origins. They get angry and exclaim “me cago en la mar” (I shit in the sea), they do something clumsy and exclaim “llevo una torrija encima” (I’m walking around with a piece of French toast on my head).

I was fascinated by those phrases, which, to the ears of a foreigner, sound so very outlandish”

They even say things like “pollas en vinagre,” which is particularly difficult to explain to a foreigner, as it could be translated as pickled dicks.

The average Spanish speaker from the Iberian peninsula may not stop to reflect on some of the expressions that come out of his or her mouth, but to other people, some of these idioms can be truly shocking.

This is precisely what happened 10 years ago to Héloïse Guerrier, who graduated in Hispanic studies in Paris, moved to Spain, and now co-runs a comic book publishing house called Astiberri.

“I was fascinated by those phrases, which, taken out of their original context, or to the ears of a foreigner, sound so very outlandish. They really knocked me out,” she recalls.

So she decided to explore their origins and put her findings down in a book, with illustrations by David Sánchez, an author of comic books.

“When you stop to think carefully about the words that make up these idioms, you realize there is a major leap from the literal meaning to the figurative meaning, and that’s where it gets funny,” she says.

That was the genesis for Con dos huevos (or, With two eggs), a hard-to-classify book that combines etymological curiosities with hilarious images depicting some of the absurd situations created by Spain’s popular language.

It seems to me that colloquial expressions in Spanish are rather more crude and forceful”

Con dos huevos did not manage to cover it all, however. “Since a lot of expressions were left out, we decided to put together a second collection of uproarious expressions, Cagando leches [Shitting milks].”

“My goal was to be very literal,” explains David Sánchez, whose illustrations add greatly to the hilarity. “I tried not be deliberately funny or draw caricatures, although it’s true that the tone of the illustrations is rather humorous.”

What makes these expressions different from those of other countries? Do Spaniards use a more obscene language than the French or the English, for instance? The short answer is: yes.

“Every language has its ready-made expressions,” explains Héloïse. “There’s the ‛It’s raining cats and dogs’ in English and the ‛construire des châteaux en Espagne’ [building castles in Spain] in French, but it seems to me that colloquial expressions in Spanish are rather more crude and forceful.”

Another fact that caught her attention, she notes, was that “quite a few expressions have to do with scatology, food and religion. I think that popular colloquial expressions say a lot about a culture, its taboos and its obsessions.”

Think about that next time you talk about “hostias como panes” (consecrated wafers the size of bread loaves) or “cágate, lorito” (take a dump, little parrot).

Another good thing about Cagando leches is the way it shows how the Spanish language naturally creates weird and twisted images.

“I was struck by the surrealist, almost unsettling side of some idioms, if you take them literally,” says the author.

We are talking about expressions like “tener los cojones de corbata” (to wear your balls as a necktie) or the above-mentioned “pollas en vinagre,” which is one of Guerrier’s favorites.

“It’s true it sounds quite bad, but the truth is, it has nothing to do with male genitals!” she reveals. The “pollas” in question are actually a type of bird also known as “gallineta,” which is pickled in some parts of Spain.

“No tengo el chichi para farolillos,” literally says “my pussy is not in the mood for Chinese lanterns”

But even they ran into the odd expression that was impossible to convey in images, such as “No tengo el chichi para farolillos,” a phrase that was coined by television screenwriters and which roughly means “this is the wrong moment for that,” but literally says “my pussy is not in the mood for Chinese lanterns.”

“The truth is, I couldn’t see a convincing way to illustrate this, despite going over and over it because it was an expression that Héloïse wanted to include in the book,” says David Sánchez.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.