Prisoner of dictatorial business links

Valencian businessman had to spend 59 days hiding out inside Spanish Embassy in Malabo

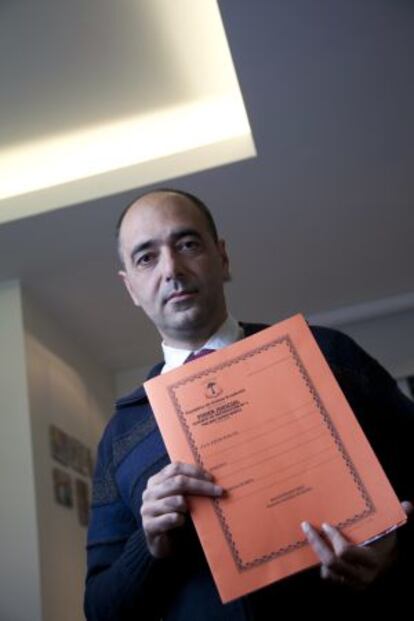

Roberto Cubría, a 45-year-old Valencian businessman, has just spent 59 days hiding out inside the Spanish Embassy in Malabo, the capital of Equatorial Guinea. He slept on a couch in the library and washed up in the swimming pool shower. He never went out by himself out of fear of being arrested, or worse.

Cubría has nothing but praise for the “exceptional” treatment he received from embassy personnel, but feels “ashamed” that his own country did nothing to stop the extortion that he feels the victim of.

Cubría traveled to the capital of the former Spanish colony in West Africa on December 11, his return ticket booked for four days later. His goal was to oversee the construction of some warehouses that his company, Soluciones Modulares, had sold to Gao Services, and to resolve a friendly dispute over the price of new changes that the client was now requesting. Gao’s representative in Spain, Antonio Olo Nchama, was going to come with him, but bowed out at the last second. He did ask Cubría to take some toys for the children of his stepsister, Genoveva Andeme. Roberto Cubría paid for the toys out of his own pocket: 600 euros.

He was picked up at Malabo airport by Faustino, a police officer working for Genoveva. Cubría was surprised at not getting his passport back, but Faustino told him there were extraordinary security measures in place due to a summit of African states, and assured him that he would personally pick it up for him. Over the next few days, Faustino kept making excuses even as Cubría inspected the prefabricated warehouses and told Genoveva that he would send the last pending warehouse when Gao paid for the additional expenses resulting from the changes. Genoveva did not like the idea.

On December 15, Roberto was unable to fly back to Madrid as he was still without a passport. He called the Spanish Embassy, and received two surprising pieces of advice: he was told not to go to the police precinct to get his passport back, and to instead leave his hotel and move into the diplomatic mission.

Diplomatic work to get his passport back yielded no results, so the Spanish consul gave Roberto a safe-conduct and had embassy personnel escort him to the airport on Christmas Day. His suitcase was already on the plane and he had his boarding pass in his hand, when a police officer blocked his way.

The National Security Minister of Equatorial Guinea, who had previously told the embassy that Cubría would be allowed to leave the country, now said he had to review the case.

Meanwhile, Gao’s representative in Spain called Cubría’s wife and, mistaking her for a secretary, told her that her boss was in Equatorial Guinea and would not get out until he delivered the last warehouse. He added that he knew where the Spanish businessman lived. Olo called several times more, always in the same threatening tone.

At the same time, Genoveva filed a complaint against Cubría for fraud back in Equatorial Guinea. She accused him of selling her poor quality material and not having built the last warehouse. A technical expert certified that the product was of adequate quality and the company that made the panels for the last warehouse confirmed that it was ready for delivery.

Genoveva filed her complaint on December 17, a week after the Spaniard’s passport was taken from him. The judge, who did not begin investigating the case until January 16, never forbade him from leaving the country. When Cubría asked why he was not getting his passport back, the reply was: “Ask the people who took it away from you.”

The judge recommended that Cubría reach an out-of-court settlement with Genoveva. The embassy gave him the same advice. The proceedings could take months, and he would continue to be stuck in Equatorial Guinea. Cubría proposed to make the delivery of the last warehouse and payment for the changes simultaneous. Genoveva refused. Cubría was finally forced to yield.

On February 14, after Olo picked up the material in Spain, Genoveva pulled her complaint and Cubría got his passport back. The price for his freedom was more than 50,000 euros, which came out of his parents’ savings and a bank loan with his house as a guarantee.

Genoveva Andeme Obiang is an influential woman. She has a diplomatic passport and a police officer as her private bodyguard. She is deputy director of BEAC, the Bank of Central African States. In 2011 she bought a house in Maryland for 600,000 dollars. But above all, she is the daughter of the country’s dictator, Teodoro Obiang, who has been in power since 1979. As a major oil producer, Equatorial Guinea has significant business links with developed nations, including Spain, despite widespread concerns over egregious human rights abuses in a country where Obiang has been described as a “god.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.