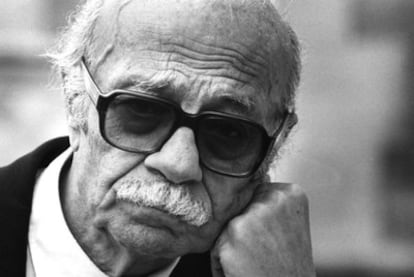

Argentina's human-rights activist and literary great Sabato dies at age 99

Cervantes Prize winner helped forge prosecutions of past military dictators

Thousands of mourners paid their last respects on Sunday to one of Argentina's most famous novelists, Ernesto Sabato, who died at dawn on Saturday, two months before his 100th birthday.

The author of Sobre héroes y tumbas (or, On Heroes and Tombs) and El túnel (or, The Tunnel), Sabato was tormented for many years by his country's violent past, as he discovered lurid details of Argentina's brutal 1976-83 military dictatorship during his term as chairman of the National Commission on Disappeared People (CONADEP).

A tribute to him was scheduled for Sunday at the Buenos Aires Book Fair, but he had already made his apologies because he was suffering from a bronchial infection he could not shake off, his companion Elvira González Fraga said. The prolific writer was buried at the Malvinas Argentina cemetery, outside the capital, near where he resided.

"My father's biggest virtue was his honesty," said his son Mario Sabato, who made the highly acclaimed documentary Ernesto Sabato, My father, with films and other materials taken from 1952 to 2007.

Born to an Italian father and Albanian mother, the late Sabato is considered one of the greats of Latin American literature not only for his novels, which include Abaddón el exterminador (or, Abaddon the Destroyer), but also for his numerous essays on the human condition. He won the Cervantes Prize in 1984, when he delivered a speech in which he described Don Quixote as "a mere mortal, a tender helpless wanderer; the man who once said that freedom, as well as honor, can be accomplished and one should risk one's own life in seeking it."

Sabato's wandering life, marked by literature and its ethical commitment, led him to declare in his later years that he felt closer to "anarchy-Christianity" than to the communism of his youth.

The writer first worked as a physicist in Zurich, but very quickly began his literary activities and struck up a friendship with the so-called South Group, where he met Victoria Ocampo and Jorge Luis Borges, another Argentinean legendary literary figure with whom Sabato always maintained an adversarial relationship but one that gave rise to the 1976 publication of his beautiful book entitled Conversations with Jorge Luis Borges.

After his first major novel, El túnel (1948) - an acute psychological test full of irony, as well as the bitterness and pessimism that marks all his later works - he won immediate recognition not only in Argentina but also around the world. His second novel, Sobre héroes y tumbas, confirmed his reputation as a highly original author and garnered him a place among the greatest writers in the Spanish language.

Ernesto Sabato's life cannot be understood without recognizing his role as a fighter for human rights and his commitment against the military dictatorship - even though he attended a lunch with General Jorge Videla shortly after the coup, also attended by Borges.

Sabato changed his views after he learned about the continued killings and human-rights abuses carried out by the dictatorship and, as recounted by journalist Magdalena Ruiz Guinazu, "signed all the petitions to condemn the loss of lives of those who appear to have been kidnapped."

After the dictatorship, Ernesto Sabato was commissioned by the first president of the new democratic era, Raúl Alfonsín of the Radical Party, to be part of the newly created CONADEP. The commission's research team gathered testimony of some 8,960 disappearances and carefully documented the existence of 340 cases of illegal detentions and torture.

The report, entitled Never Again but also known simply as the Sabato Report, was delivered to Alfonsín in a memorable event for many Argentineans on September 20, 1984. It led to the prosecution and conviction of senior members of the military juntas of the dictatorship, who were sent to jail. Sabato was opposed to the laws of Punto Final and the subsequent pardons granted by the Peronist President Carlos Menem.

Ernesto Sabato suffered from severe depression for many years and spent his last days confined to his home. He practically stopped writing but continued to paint - his second artistic vocation.

He knew that one day he would be reconciled with literature. "I did not want to be pigeonholed into any literary trend," he once said. "My relationship with literature is the same as that of a guerrilla and a regular army."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.