How a liqueur made by French monks became wildly popular and ran out

Inventories of Chartreuse have dropped sharply, but the Carthusian religious order doesn’t want to increase production

In his autobiography, Born to Run, Bruce Springsteen wrote that when he first started drinking, he got hooked on Chartreuse. The pale, captivating yellow-green liqueur also fascinated characters like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby, who often offered visitors to his apartment a taste of Chartreuse from a cache hidden in a cupboard.

Hiding your Chartreuse adds a touch of mystique to the liqueur, and these days, more people are doing just that. A shortage in the United States has become unexpectedly drastic at bars from coast to coast, where the coveted elixir is a key ingredient in cocktails like Strawberry Brava, Last Word and Sammy’s Paradise.

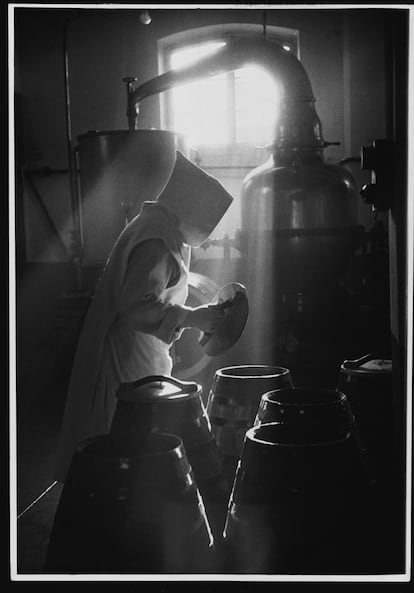

What is the reason for the scarcity of this extraordinary liqueur with medicinal, fever-relieving and digestive properties? The drink is based on a secret recipe of 130 botanical ingredients from an ancient manuscript about the “elixir of long life.” It’s produced in France under the protective embrace of the Isère mountains by the Carthusian monastic order since the 18th century. So, why is it so hard to find? The answer is simple — the monks have steadfastly refused to increase production, turning a deaf ear to the ever-growing demand.

In a profit-driven world, it may seem unusual to consider spiritual rewards. However, the monks of Chartreuse have chosen to remain true to their values and focus on their motto: “The Cross is steady while the world turns.” Emmanuel Delafon, president of Chartreuse Diffusion, told the French media: “Growth for growth’s sake does not make sense for us.” Rev. Michael K. Holleran, a former monk who oversaw Chartreuse production from 1986 to 1990, said in a Terre de Vins magazine article, “You can’t make that much Chartreuse without upsetting the balance of monastic life.” Climate change has also made it more difficult to obtain the necessary quantities of all the botanical ingredients. Inventories are also limited where it’s produced — the Caves de la Chartreuse in Voiron — and in the surrounding villages.

A recent New York Times article about the Chartreuse shortage focused on Joshua Lutz, a health technology professional from Huntington Woods, Michigan. For over 20 years, he has had a fondness (and reliance) on his favorite liqueur. When he noticed that finding a bottle was becoming increasingly difficult, he started traveling across the country and even abroad in search of Chartreuse.

During the pandemic, when everybody and their mothers suddenly turned into professional mixologists (at home), Chartreuse consumption skyrocketed in the United States to annual sales of $30 million, according to Chartreuse Diffusion.

To grasp Mr. Lutz’s store-to-store journey and America’s devotion to this drink, one need only recall the memorable bar scene from Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, where friends downed shots of Chartreuse with undeniable gusto and fascination. Tom Waits called it out in his song Til the Money Runs Out, and Frank Zappa did the same in Fifty-Fifty. ZZ Top dedicated a whole song to it: “Chartreuse / You got the color that turns me loose / Chartreuse / That color just turns me loose.” The name of the song? Chartreuse, of course.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.