Patti Smith: ‘I’ve never seen a world so driven by power and money’

This year, the singer-songwriter celebrates the 50th anniversary of ‘Horses’, the album that made her famous, and releases her memoir ‘Bread of Angels.’ Her voice, steadfast in its commitment to the world’s just causes, continues to resonate through her writing and performances

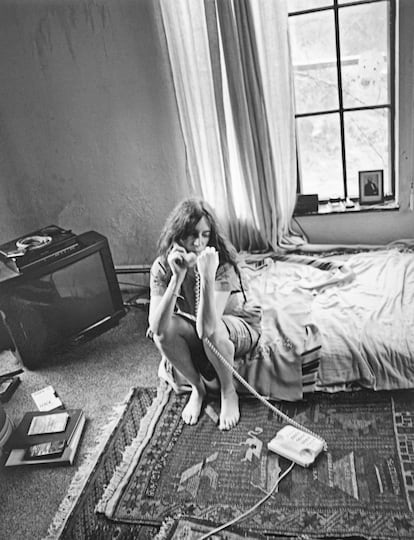

They call her the godmother of punk for a reason, and not just because she began her career reciting poetry in churches. Patti Smith, 78, still follows her own profane rituals to the letter and possesses a private, personal symbology — objects that may seem banal but, for her, contain emotions and memories, Proust-like in their power to condense time.

At the moment of our interview, the artist has just carried out two of these rites. She landed in Madrid at 3 p.m., fresh from Dublin, and went directly, as is her wont, to the Reina Sofía Museum to pay homage to Guernica — a ritual she used to fulfill weekly when the painting was housed at MoMA in New York. Then, to eat a bocadillo de calamares and drink a black coffee while people-watching. She arrives at our meeting caressing a book by Rimbaud, her beloved Rimbaud, to whom she owes her vocation as a poet. The volume was given to Smith by Lumen, her publisher in Spain. “I’ve been accumulating objects. I have some postcards that appear in this book, manuscripts by Artaud, Emily Dickinson… but I am not really a collector. I save things that allow me to remember and feel good. A stone I found at the tomb of Osamu Dazai, the copy of Pinocchio I read as a little girl… though if I had to pick one thing to keep, it would be my wedding ring,” she says, pointing to the simple gold piece of jewelry now hanging around her neck. “I could do without the rest. But not this,” she says.

The next day, Smith would go to the Teatro Real to sing every track of Horses for a clearly devoted audience. The city was the second stop on her European tour in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the album that made her a star, seemingly against her will. But that’s not all. She also just published Bread of Angels, her definitive memoir. The book traverses her entire life, not just eras of it, like her previous books.

At 78, Smith still has the energy of that 20-year-old who had so much to say. Creating, regardless of the medium, is what makes her happy. “Writing is solitary. Acting is the opposite, it’s collective, it’s electric, it’s communion. I love both, but they come from different parts of me. When I write, I am building something in silence. When I act, I am sharing what I’ve built. I couldn’t live just as a performer, however. Writing keeps my feet on the ground, it’s where I understand things. Acting is where I celebrate them,” she says.

Question. As prolific of a writer as you are, you spent 10 years on this book.

Answer. Because I didn’t expect to write it. I actually had a dream where a messenger came to my house and gave me a book, and it was white and had a white ribbon. It had four photographs of white dresses that were mine. My wedding dress, the white dress that Robert [Mapplethorpe, the photographer who was her life companion and who stars in Smith’s book Just Kids] gave me, the white dress my brother gave me and a white communion dress. I never had a communion, mind you. And I had written it, it was the story of my life, and the only photographs in it were those dresses. Then I woke up and I had my hands in front of me as if I were holding it up and I thought, this is a sign that I should write it. But I wrote for awhile and then I stopped, because it was about my life and there is so much loss in my life. Sometimes I needed to stop, because it was affecting me.

Q. There was a moment, in the middle of the process, when you discovered that your father was not your biological father.

A. Yes, I stopped writing it for a few years because I had to process who I was, but that wasn’t a bad thing. My father was a great man who I learned so much from. It’s just that I had to process it, and then decide what to do with that information. I decided to include it, because we all have had unexpected things happen to us and often, we don’t know how to deal with them. People asked me if I hated my mother because of it. And I don’t. I am who I am because my mother and father raised me. I am their daughter. My home provided shelter for homosexual couples, we had parties for people who were rejected by their families during that period. I grew up free. My father was very philosophical, he read a lot. My mother was much more pragmatic, but I am who I am thanks to them, though it has been difficult for me to capture the essence of the whole story. Look, now that I’ve finished this book, I’m going back to fiction, which is more gratifying.

The majority of the books Smith has published have been inspired by mourning. In fact, Bread of Angels came out on November 4, Mapplethorpe’s birthday and the anniversary of the death of her husband, musician Fred “Sonic” Smith. But pessimistic her books are not. “Of course, many times I have had to stop writing for a long time, to breathe, to put my ideas in order. But mourning is not the end of love; it is its proof. You cry because you have loved deeply. And if you can still feel love, you can still feel hope. That is what keeps me moving forward. I think that is a kind of gratitude for having once had what you lost. When I feel that, I write, or I sing, and that transforms the mourning into something that can breathe.”

Gratitude makes her world turn. Gratitude for what she has experienced, for her two children, for the people she has known and from whom she has learned. “When you say thanks you are more free, you remove links from the chains. One has to know how to process all the good that comes your way, but realistically,” says Smith, the recipient, among many other honors, of a National Book Award, a French Order of Arts and Letters, and an honorary doctorate from Columbia University. “It’s very nice, I don’t know, to get into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame or have medals or for it to seem like people love you a lot, even when they don’t know you at all, but aside from that, it’s not everything. For me, there’s no fame or money that eclipses writing three good pages in a row. But I also don’t think that I’m writing a masterpiece when I’m writing them, I don’t know if I’m explaining myself.”

Question. You have always had a complicated relationship with fame.

Answer. Well, it’s because I appreciate it. Last night, I gave a concert for 5,000 people in Dublin, many of them young people, and I could feel their love. But it is my duty to perform. My father wasn’t in any party, but he had a very socialist mindset. He didn’t want positions at work that were above the other workers. My mother was a waitress. My father worked at the factory, they were both very intelligent, very well-read. From them, I learned to value good people over everything. My mother, when I was leaving a concert and was very tired, forced me to stick around to sign things for the fans. She told me, “Don’t forget who got you here. It’s because of them you’re on that stage.” I’m trying to say that I’m thankful, but I put it all in perspective.

Q. But at the same time, you are a mythomaniac. You had a very particular encounter with Bob Dylan, in fact.

A. Yes, well, I still don’t know why I reacted like this, but when he came to see me and say he liked my poetry, I burst out with “I hate poetry.” And I ran away, thinking to myself: Oh my God, it’s Bob Dylan. The crazy thing is that he liked that I had been like that. I suppose because we both are of a rebellious nature, and are conflicted about fame. My first reaction was to reject it.

Q. In your life you have rejected many things — like when they wanted to retouch the Horses album cover, which is now iconic, though it might not have been if you’d agreed. Or when you refused to change the arrangements or lyrics. It takes a lot of courage to stay out of the dynamics of success.

A. No, it’s not hard. I mean, it’s hard if you have a certain goal. But I didn’t care if they told me my hair was messed up or if I left this or that song in, the album wouldn’t sell. Fine, then it won’t sell. I knew what I wanted and I knew what I wouldn’t do. I don’t know, people have to make their own decisions. I’m not criticizing people who take a different path. We have a lot of great pop stars who are very entertaining. I enjoy their work, though they do things that I would never do.

Q. You belong to a place and time, 1970s New York, that no longer exists. Perhaps, because there are no artists left who come from working-class families.

A. I hadn’t thought about that, but it’s an interesting theory. Maybe that’s why we have a different work ethic. But I also think that I come from an era in which we didn’t have social media. Robert and I didn’t have a television or a telephone, just a turntable. There was no pressure or scrutiny, or possibility of getting famous in record time. And I also think that I come from a time in which being a writer or a musician was vocational, like being a doctor. Now we are in an era and a culture in which the goals are different, so the motivation is different. There are young musicians that approach me to get a publicist. Wait, you’re 20 years old, what do you care about a publicist? I have never had one.

Q. In your book, you talk about an incident with some Italian fans in the 1970s where they asked you to help their family members, who were political prisoners during the Years of Lead, and you felt so impotent that you almost left music.

A. I didn’t even know I was famous in Italy. And the truth is that I felt really ashamed because I didn’t even know about the country’s political situation. I came from a rural environment and I knew the political problems around me and the ones in New York, and not a lot else. Suddenly they were asking me to use my voice in a situation I didn’t know about. I did my research, of course, and I realized that there were a lot of unjust situations that I didn’t know about, because at the time we didn’t have the means of finding out about them. But I also realized the responsibility that comes with being who I am. I am not an activist, I believe in human beings, and I speak and make decisions when I feel that I have to do so.

Q. Has speaking openly cost you?

A. When I demonstrated against the war in Iraq, I had a few very bad years, because that was not well looked upon in the United States. I don’t know, everyone knows my opinion on Palestine. Many years ago, I did a concert in Israel, I saw the situation and from then on, it’s been a subject that keeps me up at night. Sometimes I’m walking on the street in New York and they call me antisemitic, or they tell me I don’t care about the hostages. Of course I care about the hostages, but I’m not going to sit down to explain everything to them. They’re not going to bully me. I’m not a politician, nor do I wish to be one. I’m an artist and a mother. Well, first I’m a mother and then an artist, though I have spent more time as an artist than as a mother. I don’t know, it really frustrates me that we are in a world in which everything has to be black or white.

Q. Have there been moments in which more has been demanded from you than you could give, in that sense?

A. Of course. On occasion, I have accepted gigs for money. I haven’t gotten rich, and I have to take care of an entire family. My sister has a lot of medical bills, and sometimes I do jobs to help her. When my husband died, I had to go back to playing because I didn’t have money and I had two children. I actually got an offer from Spain, I don’t know now whether it was an investment fund or a bank or something like that. It wasn’t that much, but at the time it really helped. I don’t always do it, I have turned down a half million dollars because it was from a pharmaceutical company. But I remember that I came here, and there was a press conference and they said, “Patti, why are you doing this?” And I answered, “I have two small children and if one of you is against what I’m doing, perhaps you’d like to help me pay the pediatrician.” I make decisions according to the needs of my people. I have my principles, but also the right to adjust them when necessary.

Q. What have you learned to leave behind over the years?

A. So many things. The need to always be right, for example, which is something that the current world seems to lack. And that things will turn out how you imagined them. It’s freeing to doubt, to try to see things from another point of view, though that doesn’t make me hold back on my own opinions, of course. Above all, I have learned to deal with pain. In this book, I have written things that I never though I was capable of writing. For example, about my accident, when I fell onstage and broke my neck, and about what happened afterwards. And about my family and loss. Now I feel so much more at peace.

Q. Do you still believe that the people have the power?

A. Yes, the problem is that we forget how to use it. I look at the world and I despair. In the United States, we are living the worst of all possible scenarios, and I grew up with Eisenhower in power, so you know I’ve had time to see things. Everything is very divided, they don’t want anything that will bring us together. And now people use their voice, go out into the streets, and receive all kinds of punishments just for being American — well, not American, for being a person. So yes, I think that the line of that song, which was my husband’s idea, is more necessary today than ever, because I’ve never seen a world so driven by power and money. And at the same time, I see people who go out into the street and are not afraid. I see Greta Thunberg, who is ridiculed in my country… I see the Greta Thunbergs of the world, because there are many. I wish I were young and could have gotten on the [Global Sumud] Flotilla. But I’m 78 years old, I can only talk about it in what I write, at my concerts, and support young people. I see images from protests and there are a lot of good people out there, especially young women. Good people. Humanists.

Q. You always had faith in the next generations. In your book, you say that one of the most traumatic things was growing up, losing innocence.

A. The thing is, I was happy when I was 10 years old. With my friends, my family and my dog. I wanted to go to Never-Never Land. I was really tall for my age, and had boy and girl characteristics. As you grow up, you have to define yourself and decide. And the passage of time has brought me very good moments, but Walt Whitman’s phrase comes to mind, “I am large, I contain multitudes.” I am a mother, I take care of my family and I am the leader of a band. But sometimes I am 10 years old, and sometimes I am more of a man in the classic sense, and sometimes more of a woman. And that’s OK, I really like being 10 sometimes.

Q. It’s a way to not lose ingenuity in a world that becoming more and more hostile.

A. And enthusiasm. Do you know the book The Alchemist? I read it one day on a plane and there’s a passage in which the shepherd, who has a hard time, says the world conspired to help him because he kept up the language of enthusiasm. Well, if I were to get a tattoo it would be that, “the language of enthusiasm.” We have to be enthusiastic to be alive, to learn things, for all of it.

Q. Do you ever think about posterity? In how you would like to be remembered?

A. There are a lot of people who love me, but there are also many who don’t like me, and with social media, you notice it more. Sometimes I think about what they’ll say about me, yes. I would like for them to remember me as someone who you could trust, as someone who never tried to take anyone down the wrong path. I wish I had written a book as good as Pinocchio, but I hope that in my books, people have found comfort. When I think about posterity, I think about Just Kids, which is already 15 years old, but I still run into people on the subway asking me to sign their copy because they had it in their backpack, covered in coffee and wine stains. I don’t think I have yet written my great work, because that helps me to keep writing, thinking that my masterpiece has yet to come. I also think that I have been a person with a lot of failings and that I’ve made bad decisions, but that’s why I try to do better. As Jackson Browne sang, “Don’t confront me with my failures, I had not forgotten them.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.