Quiara Alegría Hudes: ‘When a woman leaves, there is always another woman to provide care in her place. I rebel against that’

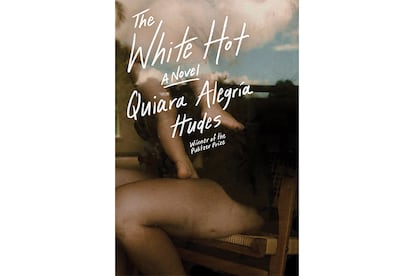

Pulitzer Prize-winner for theater makes her debut as a novelist with ‘The White Hot’

Quiara Alegría Hudes, 48, confesses that what saved her life in recent years has been writing and reading. The playwright of Puerto Rican descent rose to fame for her original soundtrack of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical In the Heights, for which she was nominated for a Tony. After being nominated for the Pulitzer Prize for theater on three occasions, she won it in 2012 for Water by the Spoonful, in which she tells the story of a Puerto Rican soldier returning from the Iraq war and having to navigate his birth family, addiction and identity crisis. Since then, the writer’s life has taken many detours, passing through motherhood, caring for sick family members and activism, the latter via her letter exchange project with incarcerated individuals, Emancipated Stories.

From her house in Philadelphia, the city that has long been the anchor to her personal life as well as her stories, she tells how for the first time, she has a project that is not based on the experience of someone from her own community, one that is pure fiction. This is important because, according to the writer, it allowed her to be more honest, darker, more direct and without a doubt, ultimately freer. Her EL PAÍS interview took place on the occasion of her literary debut with the novel The White Hot, which goes on sale November 11 and is one of the most-awaited reads of the fall.

Question. How did you decide to try your hand at literature after studying musical composition at Yale and dramaturgy at Brown?

Answer. When my grandmother got sick, I realized that she also had an American story to tell, something that I had never read in school, but that existed in my community. And I felt the need to tell other stories.

Q. Latina stories?

A. We matter, why aren’t we talked about? Why aren’t our stories told? Also, I think there is more space for our different communities in literature than in theater. It costs less, and you can get books for free at the library, that makes it easier. On the other hand, in Philadelphia, they don’t usually invite Latina playwrights to bring their stories to the stage. This morning, I spoke with Esmeralda Santiago, a writer who is a friend of mine. One of her books was the first I read in English about the diaspora, and it had a lot of influence on me.

Q. It’s a critical moment for Latinos in the United States.

A. It’s a moment of extreme terror. We have ICE entering into our communities and separating families, which has been the most horrible strategic tool in the history of this country, used in the past to terrorize Native American communities and Black families during slavery. It is a practice that has deep and very real roots. But it is also a moment of pride. We have Bad Bunny, [Sonia] Sotomayor [the first Latina Supreme Court judge]… We have genius and suffering, all at once. I am considering writing a book about what is happening.

Q. In The White Hot, you narrate the story of a teen mom who abandons her daughter. Why did you want to tell that story?

A. My mother, despite her many misgivings, had to dedicate herself to building a community. And my grandmother spent her life taking care of her children, then her grandchildren and then her great-grandchildren. She even took care of other people’s kids! I asked myself what would have happened if they had escaped that enormous responsibility of domesticity and dared to live the life they wanted. And also, reflect on how when a woman leaves, there is always another woman to provide care in her place. I rebel against that. In my novel, the father provides stability and that’s why the woman can go.

Q. You have two children. Did it scare you to take on motherhood, knowing that it was going to limit your freedom, as it does for so many other women?

A. In my case, I became a mother intentionally, out of joy, wanting to show my children a woman who lives her own life. I love them and I also love myself. I have always admired women who, through art, have shown examples of other kinds of motherhood, like Toni Morrison or Jamaica Kincaid. They are women who loved themselves and loved their freedom and their priority was not setting the table so that the family could have dinner or doing what made the rest of the world comfortable, but rather maintaining their curiosity. I wanted to build a character who broke those taboos associated with women and motherhood. That’s how April Soto was born.

Q. What does the title The White Hot mean?

A. The energy that bubbles up inside us, a kind of lightbulb that we can use for good or for bad. April, the protagonist, has anger problems. She gets into fights at school and street brawls, which brings her a lot of problems. This book tells the story of how to channel that energy and honor it, but not in a destructive way, but as a kind of enlightenment.

Q. What have the men who have read the novel said?

A. At first, I thought it was a novel that would only interest women. A novel about women, Latinas, Puerto Ricans, but now I have also discovered that it is a fathers’ story. Both my husband and my friend, Lin-Manuel Miranda, have told me that it’s the best thing I’ve written so far. I think it’s the most honest thing I’ve ever written. I was a mess when I wrote the scene where April faces her daughter’s father, and she says, “I want 10 years [for herself, away from her daughter].” It’s a fair thing to ask, but the important thing is that she’s finally asking for what she wants. So few people ask for what they need. After my mom read the book, she called me. She said, “It makes me think of all the women in our community who actually did leave.” The dads had already left, but the moms left too. And there is a secret and a quiet of history of that in the community.

Q. During Donald Trump’s first presidency, you organized gatherings of artists to discuss mental health. How are you doing in that regard now?

A. At the time, I was not in a good point of my life, so I asked some women friends if they would be interested in getting together to talk about mental health. They all accepted and brought other people with them. All women, all Latinas, all artists. The connecting thread was how we were feeling that Trump hated us, and how that sensation was destabilizing. We wanted to recognize ourselves and lift each other up. We did ceremonies, cleanses, we sang songs, we shared our work. I should organize another soon. Many of the programs that have supported my work and are dedicated to visibilizing the voice of Hispanic, Latina artists are on the chopping block.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.