Racism in the Trump era: ‘Don’t speak that shitty Spanish in my country’

The U.S. president has created a new internal enemy, the Latino migrant, who must be identified, pointed out and deported

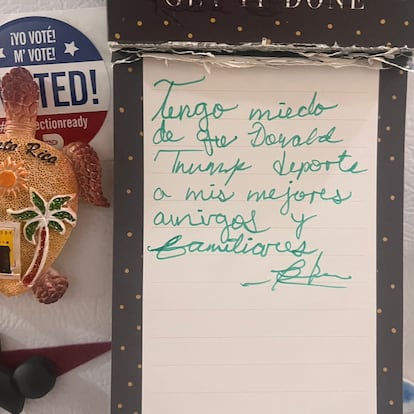

Donald Trump wants to transform the United States into a resort for white people. On January 20, he became the most powerful man in the world. He is diverting international attention to Gaza, to tariffs that can be removed and replaced, or to the ownership of the Panama Canal, while within his borders he is spreading a drift of xenophobic overtones with recipes from the past that, although he does not attempt to hide them, are blurred in the midst of a deafening noise. Trump and his government are moving forward resolutely in the creation of a new internal enemy for Americans: the Latino migrant, who must be identified, pointed out, and deported.

The goal is to carry out “the largest deportation in history.” And anything goes in order to achieve it. Schools, hospitals, and churches are no longer protected from anti-immigrant raids. Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem refers to undocumented people as “trash” or “waste.” State senators from Mississippi and Missouri have proposed rewarding citizens who report foreigners so that they can be deported with payments of $1,000. Speaking Spanish or having dark skin has become a problem: in recent raids, several U.S. citizens have been arrested just because of their appearance. The Trump administration has withdrawn the protection with which 300,000 Venezuelans entered the United States legally in recent years and has turned them into undocumented people. The U.S. naval base at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba will be the eventual destination for some of them.

Cuban migrant

Official data estimates that there are 11 million undocumented people in the U.S. With the influx of immigrants in recent years during the Joe Biden administration, the real figure could exceed 13 million. These are people who work, consume, and in 2022 paid more than $95 billion in federal, state, and local taxes. Almost eight out of 10 have been in the United States for more than five years and less than 4% have a criminal record, according to data from the United States Department of Homeland Security. But the message is for everyone: they are no longer welcome here. Fear among Hispanic migrants — whom Trumpism accuses of being responsible for an alleged wave of violence that is sweeping the country — has skyrocketed.

Mariana is terrified. If she is detained, she would rather be “thrown out” or “released” anywhere other than Venezuela. She is worried about having to pack up her things and leave the apartment in the Queens building that she worked so hard to furnish, so different from the room she lived in with her husband and daughter three years ago when they arrived in New York. She explains her situation crying, as she cries every night since she learned that Trump would withdraw Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for Venezuelan migrants.

Mariana, 36, was one of the last 300 beneficiaries of the program in 2023, when the Democratic Biden administration extended the status with which some 300,000 Venezuelans remain legally in the U.S. and have work permits by 18 months. Her benefits expire in April because the Republican administration considers Venezuela to be a safe country today, to which its citizens can return without fear, despite the fact that Trump himself has called it a dictatorship. Mariana barely sleeps or wants to leave the house. She has spoken with her husband about what she calls a “plan B” in case Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers knock on the door of their apartment and put the three of them on a deportation flight.

— Let them leave me stranded in Mexico and I’ll see what I can do, or in Colombia, or somewhere else, but I can’t go back to Venezuela.

Mariana was a teacher for 12 years at a school in the El Junquito parish, in the northwest of the Libertador municipality in Caracas, a place where everyone knows everyone. There, people knew that she thought differently, that she complained that her salary of 200 bolivars was not enough “even for a kilo of cheese”; about the politicization of classes for children, where, according to her, only Hugo Chávez, Che Guevara, or Cuba were talked about; or how the bag of food that the state gave her full of “rice with weevils and bad flour” was humiliating. Mariana quit her job as a teacher and set up a stand selling fruits and vegetables. Mariana was seen as a troublemaker.

Almost five years ago, when her daughter had just turned one, hooded men broke into their home and kidnapped them. They asked for her car keys, drove them to a wooded area, tied them up, and extorted money from Mariana. She recognized one of the attackers. It was her neighbor.

They decided to sell everything and set off on a journey to the U.S. border. They turned themselves in to the authorities, were detained for 10 days, and then released on humanitarian parole. In three years, Mariana has worked in construction, cleaning, doing nails and hair, cooking, babysitting, and in a chocolate factory.

— When they announced the news [of the end of TPS] I was in shock. I thought they were going to deport people who had done wrong. This rocks your world. I already have a home, my husband has a stable job, our daughter is in school. It would be like starting from scratch again.

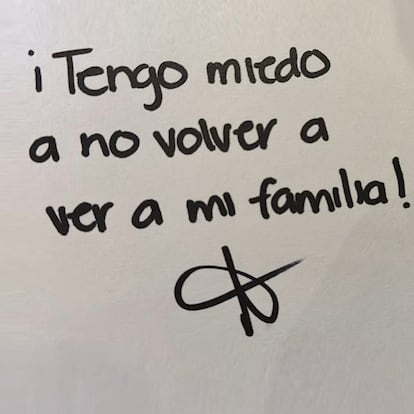

The message that is being passed on by word of mouth is that one must be prepared for the worst. New York schools hold meetings to inform migrant parents about their rights and those of their children. Associations are organizing to explain how to proceed in the event of an arrest: not to open the door to anyone without a court order, to seek legal advice, and not to sign any documents. Some, out of fear, do not take their children to school; others have stopped leaving home but the majority have to get on with their lives and, like those who prepare a survival backpack in earthquake zones, thousands of migrants are looking for a plan B. For example, giving up custody of their own children.

Father Vidal Rivas does not have children, but at 60 he and his wife may find themselves caring for 14 youngsters, aged from three to 17. Five families from his parish, St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Hyattsville, Maryland, have given him custody of their children in the event that ICE agents detain and deport them.

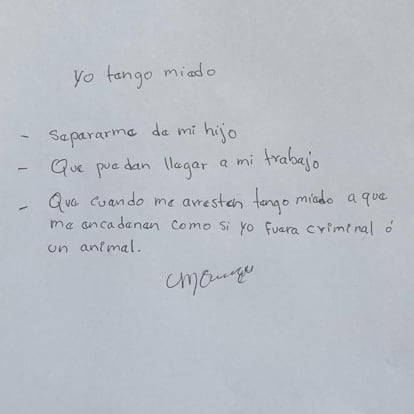

Honduran migrant

- Of being separated from my son

- That they might come to my work

- That when they arrest me they will chain me up as if I were a criminal or an animal. -Morena

“It is a lot of responsibility. It would totally change my life. I am even waiting for a family with a two-month-old child to give me guardianship,” admits Rivas, who does not hide his concern. However, he himself has encouraged them to fill out the forms so that they are prepared.

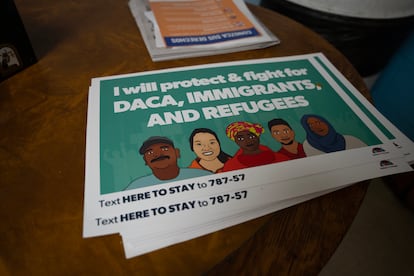

Among the 650 faithful who attend his services, 85% are Latino migrants and most of his masses are conducted in Spanish. Rivas, who arrived from El Salvador in 1998 and has U.S. citizenship, estimates that around 25% of them are undocumented, although he does not know their exact immigration status. There are those with TPS, beneficiaries of DACA (the program for those who arrived illegally when they were children), some with temporary work visas and others without any permit. “Some are not coming. The panic is such that they do not even leave their homes,” he says.

In the event of a parent’s deportation, guardians would be required to follow the parents’ instructions in their absence. Some ask that the children be sent immediately to the country to which they would be deported, to be reunited with them. Others prefer that the children be cared for until they graduate from high school. Family separation is always traumatic, but in many cases parents prefer that the children remain in the United States rather than return with them to the country from which they fled.

María (not her real name), a 35-year-old Honduran, is one of the mothers who signed the document leaving her son in the care of Father Rivas. “My son was born here and it would be in his interest to study here. I do this with all the pain in my soul. It is not because I want to, my heart is broken. I am terrified, insecure. More than anything, I would never want to be separated from him,” she explains, holding back tears.

She crossed the U.S. border illegally a decade ago. She does not want her nine-year-old son, who is a U.S. citizen, to have to leave and live in a country plagued by violence. She works as a cook in a restaurant, which she stopped going to for a few days because of the fear of raids, but she has already returned to her job. “When you are a single mother, you have to keep going.”

Civil rights organizations are encouraging migrants to make plans to leave their children with a guardian rather than having them placed in state custody in case they are detained or deported. “It’s devastating to see parents break down in tears as they fill out this paperwork, knowing they must prepare for the unthinkable,” says Monica Gray, executive director of YWCA NCA, an anti-racism nonprofit. “But what’s even more heartbreaking is seeing children in the room repeating phrases they’ve been taught in case they are detained by ICE. No child should have to live in that kind of fear.”

The parish is not limited to providing spiritual guidance. Such a dramatic situation is mobilizing the community and Father Rivas says that many American families are offering to take in the children and to help financially. “The solidarity that is awakening is very interesting,” he says. Others have offered to watch the parking lot and the entrance to the church, to warn in case the feared ICE agents make their appearance.

The same thing is happening in many other churches and places of worship across the U.S., where religious leaders are preparing strategies to protect immigrants from raids. As in the Christian El Buen Pastor church in Mesa, Arizona, where Pastor Héctor Ramírez receives migrants released from the detention center every Thursday. Before, they would stay overnight, but now they are afraid that word will spread among local residents. “They begin to spread rumors that people are staying overnight, that we are protecting them, and we do not want to take that risk. There are those who do not like people from other countries coming because they think they may be criminals. Hearing the news, they become racist, even if they are Hispanic or from any other nation, and they turn against the migrants who are arriving,” says Ramírez.

In at least three states, authorities have arrested people for impersonating immigration agents and harassing Hispanics. “Don’t speak that shitty [Spanish] in my country,” a 33-year-old man tells the occupants of a vehicle he stopped on a South Carolina highway, in a video shared by the victims. “Where are you from? Are you from Mexico? Go back to Mexico!” continues the man, who has been arrested on charges of false imprisonment and impersonating an officer.

Trump’s Machiavellian plan is both loved and feared. While he sows absolute terror among a sector of the population, he fosters among his supporters the image of an all-powerful, efficient, and unscrupulous leader. The campaign of mass deportations enjoys broad popular support. A survey by The New York Times and Ipsos conducted between January 2 and 10 revealed that 55% of voters strongly or partially support such plans and 63% agree with expelling those who entered illegally during the last four years of Democratic governance.

Many of the president’s decisions, however, will come up against the courts. Legal experts question whether it is possible to strip a migrant who entered the country legally overnight or, as Trump has promised and decreed, eliminate birthright citizenship for children of foreigners born in the United States. This order was to have gone into effect on February 1, but it was temporarily blocked by two judges who maintain that it is unconstitutional. If applied, children like the son of Nata, a 40-year-old Mexican woman, would not be American citizens.

Mexican migrant

The last time Nata and her son went to McDonald’s in Texas, the boy asked his mother to go inside with a hood on because his older cousin had told him that migrants are no longer welcome in the United States. The youngster, eight years old, asked her to give him the money to pay while she sat down, so that she wouldn’t run into anyone. Nata preferred not to go into McDonald’s that day.

She arrived in the United States when she was pregnant, across the border from El Paso, and has since survived by selling bread. Her son, who was born in Texas and speaks both languages, likes Legos and superheroes, and wants to be a robot designer.

Nata feels that since Trump arrived, the speed of time is changing and she no longer has enough to put her things in order. She is afraid of being sent back to Mexico, where she has no friends and family left and nowhere to sleep. As soon as she could, she got her son an American passport, just in case. “I also need to give his grandmother a power of attorney with no expiration date, to give her parental authority, in case they arrest me. We need to have everything in order soon,” she says. If they arrest her, she has already decided that she will sign the voluntary deportation. “I don’t want to be in jail.” Her mother, who is a legal resident, would take care of the child. Although sometimes she regrets that decision and thinks it would be better to take him with her. Who knows.

Her son, although he doesn’t know anything for sure, swallows the vibrations of fear that circulate in his room, where he sleeps with Nata. He sees the concern in the eyes of his aunts and uncles and hears his cousins talking. He has become rebellious, nervous like a cat, and sleeps poorly. “That makes me sad,” says Nata. “I can feel fear, but I don’t know what to do because my child is more afraid than I am.”

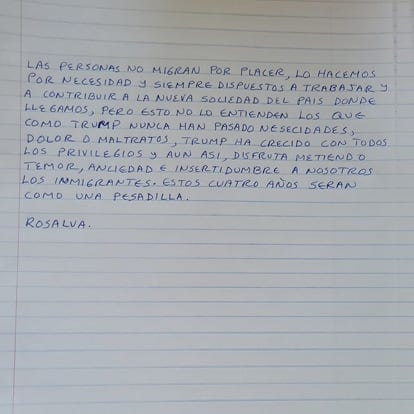

Mexican migrant

Credits:

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition