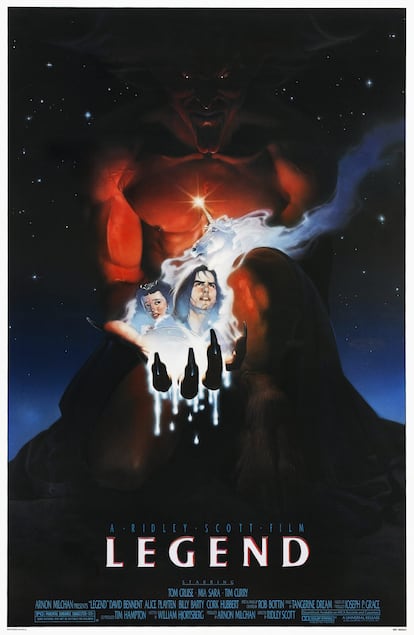

The story behind Tom Cruise’s only major flop: Fires, crocodiles and a flailing Ridley Scott

Forty years ago, ‘Legend’ hit theaters, but neither the filmmakers nor the audience seemed entirely sure what the movie was about

Ridley Scott has said that he had an epiphany just before turning 40, in the spring of 1977. He had just presented his first film, The Duellists, at Cannes, and his younger brother, Tony, convinced him to go see Star Wars — the $11 million galactic fable then making waves, directed by a certain George.

Sitting in a movie theater on the outskirts of London, the Scott brothers realized that the industry they hoped to break into was on the verge of a decisive transformation. Cinema, Ridley predicted, was about to become more simplistic, largely abandoning the artistic ambition of the 1970s — but it would produce films that were increasingly expensive, spectacular, and profitable.

Alien was the result of that epiphany. If we’re going to play this game, Ridley told Tony — who at the time was still directing experimental shorts on budgets of less than a thousand pounds — then let’s do it seriously, and accept the consequences. At that point, a generation of British directors coming out of advertising (Alan Parker, Hugh Hudson, Adrian Lyne, and the Scott brothers) was making strong inroads into the world of cinema, and producers like Jerry Bruckheimer were eager to welcome them under their protective wing.

The British are coming, they said in Hollywood. And although Lyne, Hudson, and Parker arrived a bit earlier, it was Ridley who came to stay, earning $104 million with a film that had cost between $10 and $14 million (estimates vary) and in which Fox lost faith in weeks before filming wrapped.

An Englishman in Hollywood

Rudyard Kipling said that success and failure are a pair of impostors to be treated with equal disdain, but today we know that the success of Alien transformed Scott into a different man. The filmmaker from South Tyneside had seen advertising as a springboard to propel himself into the big leagues of audiovisual arts and aspired to make ambitious, substantial films like those of Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola. But once he recognized that the new genre cinema held immense potential, he decided to focus on it exclusively.

Around 1980, he abandoned his pet project, an adaptation of Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde, which he had begun developing before embarking on The Duellists. After spending a completely unproductive year trying to get Dune off the ground — which would eventually be directed by David Lynch — he reached an agreement with The Ladd Brothers and Warner Bros. to take on Blade Runner. He settled in a mansion in Malibu Colony, one of the most exclusive neighborhoods in Los Angeles, and it was there, while overseeing the casting that brought Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, and Sean Young on board, that he began to sketch out his assault on the skies, the contemporary fairy tale that would eventually become Legend.

In fact, the earliest references to the project date back to the winter of 1976, the period Scott spent filming The Duellists in the Dordogne region of France and northern Scotland. But at that time, he was quite determined that it would be an adaptation of one of the Grimm brothers’ tales — one of the literary references George Lucas had also considered, albeit with commendable lack of rigor, during the making of Star Wars.

In 1981, Scott changed his mind. He decided that to enjoy maximum creative freedom, it was better to write an original screenplay, and he hired New York novelist William Hjortsberg, who had published his masterpiece, the then-unknown Falling Angels, three years earlier.

The Princess Bride

The plot of Legend — that intricate tale of dryads, goblins, princesses, demons, and unicorns — was largely the product of Hjortsberg’s fertile imagination. The hired writer and the successful director worked side by side on up to 15 versions of a script that almost always exceeded 200 pages.

Together, they watched Beauty and the Beast (1946), Jean Cocteau’s cinematic poem, and agreed that they wanted to inject into their story, in Hjortsberg’s words, “an epic breath and a dark, musty beauty.” They even considered appropriating the plotline of Cocteau’s film and turning Legend of Darkness, the project’s working title, into the story of a nubile princess seduced by a monstrous creature.

When he finally had something substantial to show, in mid-1981, Scott went to Disney accompanied by conceptual designer Brian Froud and visual consultant Alan Lee, who were working on translating Hjortsberg’s fantasy universe into images. By that point, Scott seemed determined to turn Legend into a fantasy suitable for all audiences, inspired, as he explained to Disney, by the aesthetic universe of Pinocchio and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Disney didn’t bite, and before throwing himself fully into the post-production of Blade Runner, Scott decided to make a sharp turn: he fired Lee, hired Assheton Gorton, and, guided by the latter’s designs, wanted to transform Legend into a much darker product aimed at young adults, with high doses of violence and even a controversial sexual scene depicting the rape of the young princess by the demonic creature trying to seduce her.

In the end, it was Sid Sheinberg, president of Universal, who came to the rescue and showed interest in financing and distributing Legend. Scott secured a fairly generous budget of $20 million and would have gotten more if not for the poor initial reception of Blade Runner, which premiered in June 1982 and was nowhere near the overwhelming success of Alien.

This unexpected setback also affected Scott’s ability to influence the casting. For the lead role of Jack, the forest creature, he wanted Johnny Depp but was also willing to consider Robert Downey Jr. or Jim Carrey — another couple of young actors with charisma and substance. Ultimately, he had to settle for Tom Cruise, an emerging star coming off the success of Risky Business, because the producers insisted on casting a “manageable” male star, a “team player,” not a wild and rebellious talent like Downey or Depp.

For the role of Lili, the virginal princess whose unintended actions unleash a catastrophe that causes “an eternal winter to fall over the land and daylight to almost cease to exist,” Ridley insisted on Jennifer Connelly. However, the very young actress from Once Upon a Time in America was about to travel to Switzerland to film Phenomena with Dario Argento and preferred to recommend a good friend, the then-unknown Mia Sara.

Sara, who had just turned 16, gave a great screen test, and Scott accepted her without objections. The director’s priority was to cast Tim Curry as Darkness, having been impressed by his fiery portrayal of the villain Frank-N-Furter in The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Once that goal was achieved, Scott barely resisted the studio’s other decisions, including recruiting Swiss actor David Bennent, the percussionist boy from The Tin Drum, to play Gump, leader of the forest elves.

Forest fire

Scott was close to filming in the legendary Yosemite sequoia park but ultimately decided on “a less impressive but more controllable environment,” the Pinewood Studios in Iver Heath, near London. There, on the set known as the 007 soundstage — where half a dozen James Bond films had been shot, including the wild and pantagruelic You Only Live Twice — Ridley insisted on building an artificial forest worthy of Popeye’s fishing village or the farming colony in Heaven’s Gate.

It turned out that, after all, the British director wanted his towering ancient trees — and, lacking Yosemite’s sequoias, he spent a substantial part of the budget building a forest with hundreds of fake oaks, birches, and beeches up to 20 meters tall and 10 meters wide.

Filming began on March 26, 1984. Thirteen weeks later, on June 27, the forest caught fire around lunchtime, apparently due to negligence by some crew members. Thankfully, no one was hurt, but that costly piece of forest illusion was reduced to ashes. Scott had to move the remaining scenes to the natural garden at Shepperton Studios.

One key scene — the moment Jack dives into the lake where Princess Lili throws her ring — was shot at Silver Springs, Florida, because Scott was obsessed with filming it in “crystal-clear waters,” close to the idyllic purity the film sought to convey. This meant Tom Cruise spent several hours diving several meters deep in a place Scott later admitted, in the DVD director’s commentary, was infested with crocodiles — though the risk, as the filmmaker joked, “was minimal, and besides, we had a good insurance policy.”

The shoot also gave rise to memorable stories, like the endless makeup sessions that visual effects artist Rob Bottin and his team put the actors portraying magical creatures through. Tim Curry, in particular, needed three and a half hours each day to transform into the imposing Darkness, applying multiple layers of paint, half a dozen prosthetics and facial accessories, and striking horns held in place by a harness.

After his scenes, the English comedian had to spend an additional hour submerged in hot water to soften the prosthetics before removing them. One day, overcome by impatience, he tried to tear one off completely, causing skin injuries that took several days to heal. Even Scott — a director convinced that almost any sacrifice is justified to achieve the best artistic result — took pity on Curry and insisted that the heavy horns, which were causing him serious neck pain, be replaced with a lighter, hollow alternative.

For Tom Cruise, the shoot was not a good experience. The Florida crocodiles didn’t sabotage his spectacular underwater scene, but his biological father, Thomas, passed away while he was filming in England. Scott, who by then was significantly behind schedule and over budget by nearly a quarter, did not take well the actor’s need to take time off to attend the funeral.

Stoned teens

After completing the film, Scott saw how circumstances tested his epiphanic faith in big commercial cinema. On the day of the first test screening with an audience, at a theater in the Los Angeles area, the director discreetly sat behind a trio of teenagers who reeked of marijuana. Convinced that they were his natural audience — the demographic target on which the film’s success would depend — he spent the entire screening closely watching their reactions.

He soon realized that this group of wayward teens hated Legend. They found it slow, boring, and with music — composed by the veteran Jerry Goldsmith, whom Scott had insisted on hiring despite him being the most expensive option — that felt outdated, almost ridiculous.

By that point, Universal Pictures broadly shared the opinion of those three cannabis-smoking teens. Scott had been prepared to fight tooth and nail against short-sighted studio executives to defend the integrity of his work, but the reaction of those youngsters left him speechless.

What followed was a series of compromises from which Legend never recovered. Scott gave up on releasing his over two-hour cut and approved an 89-minute version for the North American market and a 97-minute cut for the rest of the world. Even worse, he resigned himself to delaying the U.S. release until April 1986 — nine months after the European premiere — to replace Goldsmith’s score with a much more contemporary selection of tracks by the German band Tangerine Dream, a favorite of director William Friedkin. The marketing campaign presented Legend as something it wasn’t: an action-fantasy film, largely concealing its nature as a dark fairy tale from American audiences.

What’s more, there was no way to avoid Legend premiering in the U.S. shortly before Tom Cruise’s Top Gun, directed by Ridley’s brother. To make matters worse, Cruise soon said that Top Gun was the role where he felt most “comfortable and free,” while in Legend he’d been reduced to “another color in a Ridley Scott painting.”

This long string of regrets, setbacks, and rushed decisions ultimately doomed a film mistreated by critics that couldn’t even recoup its direct production costs — not to mention the expenses for prints, marketing campaigns, or overhead.

It’s hard to believe today that Legend nearly buried Ridley Scott’s film career, threw into crisis the then-popular fantasy and teen horror genres, and was considered a blot on the records of nearly everyone involved. But the world of 1985 was very different from today. Back then, Mikhail Gorbachev seemed to promise a bright future for a revamped Soviet Union, and Edwin Moses — the athlete who had been undefeated for seven years and even inspired successful video games — sat comfortably on his throne. It was the time of aerobics, the ozone layer hole, emerging environmental activism, and the dying gasps of the Cold War. It was a time of impatient, bombastic cinema, expensive toys demanding instant profitability, and when they failed, careers were destroyed and major studios ruined.

Four decades later, we know Ridley Scott managed to survive Legend’s failure, though not without paying a heavy price. In fact, looking back now, the film as originally envisioned by Scott before crossing paths with those three stoned teenagers seems quite respectable. But it’s worth remembering that at the time — and for Scott himself — that movie about goblins and unicorns felt very much like the end of a creative streak.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.