‘Cinema for morons’ and ‘pompous garbage’: The first ‘Star Wars’ script that absolutely no one liked

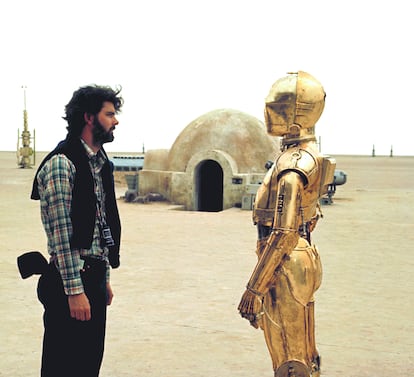

In the summer of 1975, George Lucas presented a draft he had written ‘for children between 10 and 12 years old’ to friends such as Francis Ford Coppola and Brian de Palma

Francis Ford Coppola, one of the first people to read it, considered the script to be pompous, indigestible garbage. On August 1, 1975, almost 50 years ago, George Lucas scrapped what he considered the first viable draft of what would become Star Wars. From his perspective, all that remained was to finalize the details of the production deal with Fox and begin filming in the Los Angeles area at the end of December. But to his wife, Marcia Griffin, and his partner and friend, Coppola, it still seemed like incomprehensible gibberish.

Griffin, an editor by profession and a frequent collaborator of Martin Scorsese, was particularly concerned that Lucas’ major project following the success of American Graffiti was based on a script lacking narrative flair and literary quality. She even recommended to her husband, somewhat cruelly, that he try “doing a little more reading” to see for himself how a good story is constructed.

Literary magpie

But the lack of references wasn’t the problem. Adventures of the Starkiller, Episode I: The Star Wars — the project’s working title — had been the fruit of many hours of voracious reading and troubled digestion. To begin with, Lucas had been inspired by The Teachings of Don Juan, the New Age gospel of Peruvian-American writer (and shaman) Carlos Castaneda, and the fairy tales of New York mythologist Joseph Campbell.

That pair of authors inspired the first sketch of the narrative, just a handful of paragraphs, written in February 1972, which included the following sentence: “This is the story of Mace Windu, a revered Jedi-bendu of Ophuchi who was related to Usby C.J. Thape, a padawaan leader to the famed Jedi.”

Lucas then began to enrich the stew with literary ingredients as diverse as the Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers comics, Tolkien’s sagas, the treatises on comparative religion by the anthropologist James George Frazer, the cycle of novels about the explorer John Carter written by Edgard Rice Burroughs, Gulliver’s Travels, and the galactic romances of Edwin Arnold.

Lucas, by his own admission, approached all this material with the instinct of a magpie, determined to unabashedly appropriate everything that glittered. Of course, the literary influences coexisted at all times with the cinematic ones.

In May 1973 — when all he had to show for it was a languid 13-page draft full of strange names — Lucas explained to Universal Pictures head Lew Wasserman that his film was going to be a cross between the Brothers Grimm and 2001: A Space Odyssey and that its basic narrative scheme (a teenage princess guarded by two henchmen, one tall, scrawny, and talkative, and the other short, squat, and taciturn) was going to be very similar to Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress, one of his favorite films.

Complex decisions

Lucas believed so much in the project, had invested so much time and effort in it, that he even stepped down from directing Apocalypse Now, a war epic scripted by John Milius that he and Coppola had pinned high hopes on since their time as independent producers in the late 1960s.

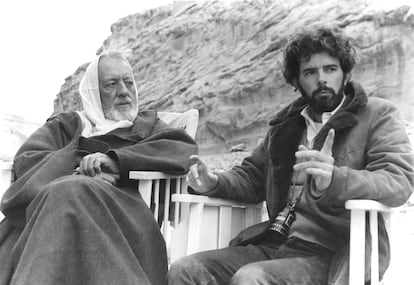

For Coppola, it was an incomprehensible resignation: Lucas was turning his back on the film that would establish him as a serious director, a true auteur in the nascent New Hollywood tradition, to dedicate the next three years of his life to making “cinema for morons.”

I don’t aspire to make a lot of money, but we’re going to make toys inspired by the characters, and many of the kids who see the film will want to buy them"George Lucas to Brian de Palma

But Lucas was fed up with Coppola’s paternal tutelage, his wife Marcia’s intellectual pretensions, and the condescending advice of members of the art-house clique like Scorsese and William Friedkin. With the first draft in hand in the summer of 1975 and the $5 million budget guaranteed by Fox, he was determined to find his own path —o ne shared by Steven Spielberg and Brian De Palma, another pair of young directors eager to restore traditional cinema.

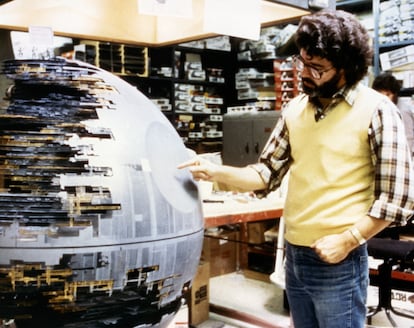

He told De Palma, his closest confidant, that his film was going to be “for children between 10 and 12 years old,” and that therefore the script couldn’t be expected to have narrative coherence or psychological depth. Children are fascinated by details, so it was above all a matter of creating a richly furnished fantasy universe for them, with multiple stimuli for their imaginations, like the attractions of a theme park: “I don’t aspire to make a lot of money,” he apparently confessed to De Palma in a moment of clairvoyance that, despite everything, fell far short of the reality, “but we’re going to make toys inspired by the characters, and many of the kids who see the film will want to buy them.”

Furthermore, the 110-page script that had been rejected wholeheartedly by Griffin and Coppola was merely the tip of the iceberg. Lucas had another 250 pages at his disposal that would lead to a pair of almost immediate sequels, so that, as his confidant De Palma recalled years later, once the first film made its mark, the second film would gross twice as much as the first, and the third twice as much as the second. “It was a five-year plan,” De Palma concluded. And it was executed with a precision and efficiency far exceeding expectations.

Lucas was anticipating the signs of the times, but he already had a powerful precedent: a few weeks before his script was ready, at the end of June 1975, Spielberg had released Jaws, the counter-revolutionary manifesto of commercial cinema, proof that a genre film of classic production and without any pretensions could gross more than $100 million.

Peter Biskind explains in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls how the three versions of The Adventures of Luke Starkiller that Lucas created alone came to be. The filmmaker locked himself in the attic of his house in San Anselmo, California, “in a room that he shared with a strident Wurlitzer electric piano” and on the wall, just behind his desk, he had pasted a photo of another of his heroes, the Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein. Although he spent long days working on the script, he also spent many reading astronaut biographies and pulp science fiction novels from the 1930s.

Biskind explains that one of his main concerns was “to introduce contemporary material into the script, while avoiding sex and minimizing the violence as much as possible.” For the character of the Emperor, a shadowy bureaucrat corrupted by power, he drew inspiration from President Richard Nixon. Darth Vader, then a secondary character, was conceived from the outset as a cross between the priest of an esoteric cult — one of Castaneda’s sorcerers — and a Nazi officer. The rest of the material flowed and oscillated with alarming intensity: “First there were too many characters; then, too few. The plot started out too simple, then became, in successive rewrites, too complex. The role of Princess Leia waxed and waned.”

“First there were too many characters; then, too few. The plot started out too simple, only to become, in successive rewrites, too complex. Princess Leia’s role grew and diminished.”Peter Biskind en 'Moteros tranquilos, toros salvajes'

Obi-Wan, who was initially the same character as Darth Vader, became his nemesis. “The Force began to have a good side (Ashlan) and an evil side (Bogan).” Anakin Starkiller gradually transformed into Luke Skywalker, and in the process, he stopped being a retired high-ranking officer who joined a rebel militia and became the New Hope, a young Messiah stranded on a desert planet being instructed in the use of the Force by the Jedi Knights, the sect of nostalgic supporters of the New Empire (soon to be the New Republic). At that time, the Force was more of a martial art than a genetically based spiritual movement.

With a little help from my friends

In those drafts, Han Solo remained a repulsive, reptilian-looking creature who betrayed the Resistance and later became what Marcia Griffin described as “a frog in a leather vest” and a reluctant ally of the protagonist. Chewbacca was originally intended to be another batrachian in a Halloween costume until Lucas decided to give him the appearance of his own dog, Indiana, an Alaskan Malamute, the only living being he allowed access to the attic during his more than two years of almost continuous confinement.

Characters like Kiber Crystal, who were meant to play a crucial role in the early drafts, eventually disappeared as Obi-Wan supplanted them, taking on more and more roles, from the mad hermit to Darth Vader’s former instructor, Luke’s uncle and mentor, to Princess Leia’s infiltrator in the Imperial periphery.

Lucas had exhausted himself from writing. He suffered frequent headaches, lower back and stomach pains, and had succumbed to the superstitions of the solitary writer: he only used size 2 pencils and blue and green lined paper, he cut off strands of hair and wrapped them in paper and threw them in the trash, and he ate in an anarchic and precarious manner.

When he considered the task complete, on that August 1 half a century ago, he was home alone. Griffin had begun work on what she considered a real film, Taxi Driver, not the puerile fable her husband was embarking on. Even so, she gave De Palma very specific instructions: “If George reads his script to you, please tell him you think it’s brilliant and that he’s very talented. I don’t believe so, but he’s going through a crisis of self-confidence, and your opinion is the only one he respects.”

The story has a happy ending. Although the creative department continued to consider the August version of Episode One: The Star Wars to be a disaster, they acknowledged that it was significantly better than the previous versions and could be rescued from disgrace with a little extra work. They suggested to Lucas that he entrust it to a team of professional writers, and he, for once, decided to follow their advice.

But only partially. He wasn’t willing to hire any of the studio’s paid hack writers — run-of-the-mill professionals who inspired nothing but contempt in him — but he was willing to show the script to two good friends, the screenwriting duo Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck. According to various accounts, they were the ones who gave the final script the focus and narrative coherence that, in Lucas’s opinion, it didn’t even need.

Lucas was rather tight-lipped with Katz and Huyck. He accepted most of their suggestions, bought their simple but accurate lines of dialogue at bargain prices, and, once their work was finished, explained to them that he had decided to take credit for the script alone because Star Wars was “his life’s work” and it didn’t seem logical to share it with anyone.

Of course, as compensation, he offered them a small percentage of future profits. Katz and Huyck agreed, pleased, as they explained years later, to have helped rescue a good friend who was suffering from a creative stalemate.

The final script was completed in March 1976, and the influence of Katz and Huyck is evident to anyone who has looked back at the earlier versions, which today are as legendary as they once seemed clumsy and absurd to the small elite of their first readers. Han Solo was never a frog in a waistcoat, Leia Organa went from a flower-power woman to the leader of a democratic resistance movement against an evil empire, Luke wasn’t an ancient general, and Chewbacca ended up embodying the galactic version of man’s best friend.

For Marcia Griffin, perhaps the least forgiving reader Lucas ever had, “Star Wars ended up being a vast audiovisual empire shaped like an inverted pyramid: at its base was a pea, George’s script.” The story of heroes and villains from a galaxy far, far away that Coppola found pompous and indigestible.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.