Wendy Guerra: ‘This book touches on very serious wounds about Cuba. And in its language, never has one of my novels been so Cuban’

The author talks to EL PAÍS about ‘La costurera de Chanel,’ an intimate story that unravels the political and social threads woven into the history of haute couture

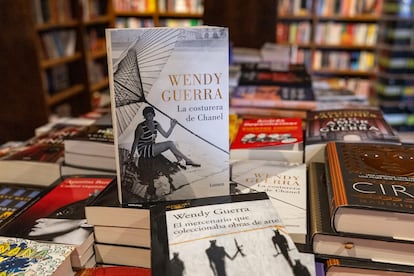

Wendy Guerra admits she could have spared her latest novel from the baggage that comes with the word “Chanel.” But La costurera de Chanel (The Chanel Seamstress, not yet available in English), published earlier this year by Lumen, would not have been the same without it. The reference in the title to a revolutionary figure in haute couture is one of the many layers the 54-year-old Cuban author has used to construct her latest book — as if it were a delicate but complex garment full of messages.

The novel, praised by critics as the most literary and stylistically refined work of her career so far, explores the contradictions of an avant-garde bourgeoisie, of free women within a rigid society, and of haute couture as a transformative form of expression.

The book tells the story of Simone Leblanc, a fictional collaborator of Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel, and immerses readers in the world of fashion and high society in France from the Belle Époque through World War II, passing through 1930s Cuba.

It may seem, as fellow Cuban writer Leonardo Padura has suggested in a review in this same newspaper, a departure from her most recurrent themes — particularly the everyday life that is always entangled in the politics of Cuba, the protagonist or setting of her previous works. But Guerra maintains, speaking by video call from her home in Miami, that, on the contrary, this novel “says many more things than many books that talk about Cuba.”

Question. How did you come about this story, which is set mainly in early 20th-century France and seems so distant?

Answer. In the house of my former husband’s family, in the midst of socialism, you would open a cabinet and there were Chanel dresses that nobody wore because it was a very modest family, of university professors and visual artists, classical pianists. Among the mystery emerged the figure of a seamstress who was not just a seamstress because she had contributed a lot to that brand. We didn’t know if it was fact or fiction, so I decided to fill all those historical gaps with something that I suppose could have happened. You say it is distant, but for me, it is very close. My relationship with fashion is not through hooded sweatshirts, but through these pieces that have that certain refinement that I believe a woman has when she makes a bow for a girl, knits, embroiders, cooks, caresses, makes love: she permeates life with that delicacy that is almost always present in the work of great designers.

Q. What lessons have you learned from writing this book?

A. What I learned is kind of a trick, which is the trick of the book. What is it? Creating layers and layers that seem to be very frivolous, but they are the real shield and the beauty that make the strength of this book. I myself, when I lived in Cuba and there was harassment of people who wrote and thought differently, noticed that my armor was dresses, suits, jackets and hats. When the political police talked to me, they couldn’t stop looking or asking questions, not because the clothes were expensive at all, because none of it was, but because of their sophistication. I think women also began to refine themselves as a sort of placebo against pain and loss.

Q. What does the Chanel fashion show in Havana in 2016 have to do with the decision to write this book?

A. The day of the show, I was launching my book in Barcelona. But suddenly, news of the show came. And that’s when I realized there was a great paradox with the economic situation, of the Cuban Revolution versus the luxury of Chanel. It’s the paradox of what Havana is, what Cuba is, what a Cuban woman is. I come from that tradition of Cubanness, which isn’t just flip-flops and drums, which is also me. It’s the sophistication of one of the first cities in Latin America where Dior sold clothes, where in art schools they taught us to eat with 13 pieces of cutlery, even in the midst of the revolution.

Q. In the book, the characters are strong women, and there are scenes that undeniably evoke women’s liberation. Do you want it to be read as a feminist book?

A. It is, because I gave birth to it. It is because I wove it, I embroidered it, I spun it. But not because there’s a feminist decree that it has to be that way, but because it itself is that, in its original sense.

Q. There is a subtle but very present eroticism throughout the book. What role does sex play in the novel?

A. The novel has moments that, for me, are revolutionary for its time. There are many forms of sexuality: there’s violence, there’s the very tender relationship — a kind of all-encompassing and bisexual intimacy where you’re not sure if the person is your sister, friend, mother, daughter, or lover — and there’s the tough, physical relationship with your husband. It has a lot of sexuality, and even more so in the fabric, in the fibers. If this weren’t my novel and I could step back from it, I’d say it’s my most sexual novel.

Q. What do you think of Leonardo Padura’s critique that this book is evidence of the weariness of writing more openly political books in the face of the immobility of the Cuban regime?

A. First, for me, having someone like Padura talk about my work, being my countryman, is an honor. You don’t know how difficult it is — and here I am a bit feminist — for a woman to be read by her male colleagues. That said, the man thinks how he lives, and that’s how Padura perceives my approach to fashion and literature. If we were having a talk at the Casa de América in Madrid, we could have a friendly debate on the topic. I know how important the tireless pursuit of beauty is, the need to put female dignity first, and the island’s understanding of phenomena like haute couture or simply the market. Why isn’t there Chanel in Cuba? Why can’t women dress well? Why isn’t there a literary market? Why can’t Padura publish in Cuba? I think this book says a lot about Cuba. It questions and touches on very serious wounds about Cuba. And in its language, never has one of my novels been so Cuban.

Q. In a few days, your first feature film as a screenwriter, All We Cannot See, will premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York. How does working on a screenplay differ from working on a novel?

A. I studied film but have written very few scripts. This novel is written from the literary tradition of Caribbean poetry. I would say it’s written and narrated from the rumination of the Caribbean waves with the tumba francesa [an Afro-Cuban rhythm with Haitian roots]. It’s a novel written visually like a period film, with a very strong spatial essentialism, very theatrical. A novel that, if filmed, would be more in intimate settings because I wanted to give the feeling that it was a conversation with oneself. Well, that was a challenge for me. I think it’s written like a film script, from the literalization of Caribbean poetry.

Q. Would you like La costurera de Chanel to be turned into a movie?

A. We are in talks with [the Mexican production company] Redrum, which made Pedro Páramo and many other important productions, about La costurera and other texts.

Q. And would you be personally involved in a possible film production of the book?

A. When I disconnect a little from the novel, time will pass and I’ll be able to. Now I can’t. A few years ago, Alejandro González Iñárritu called me and invited me to work with [Venezuelan director] Alberto Arvelo on a project he hadn’t finalized. So I went to Los Angeles to work with Alberto. And, in the heat of the battle, he suggested I write with him something that was already a kind of in an embryonic form. And that was the embryo of the film All We Cannot See, which was shot in Spain last summer, with actresses María Valverde and Bruna Cusí, and music by Gustavo Dudamel, by a very small team of independent, American and Spanish filmmakers. That day Alejandro rang me marked my closure with Cuba, because I was prohibited [from Cuba], and he told me he would help me make films if I couldn’t make novels. And it seems like my life is going down that path, in a process of developing projects, of my own cinema. Since the release of this film, there are other projects in the works.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.