‘Gene depended heavily on Betsy, and she on him as well’: Friends shed light on Hackman’s secretive life in Santa Fe

After retiring from Hollywood, the legendary actor, who recently passed away alongside his wife, never lost his creative drive

A large oil painting hangs in the main dining room of Jinja, an Asian restaurant northwest of Santa Fe, the capital of New Mexico. The painting depicts a woman sitting on a beach, gazing out at the sea. The idyllic scene, bathed in turquoise and ochre hues, is one of five works by Gene Hackman displayed in the restaurant. Recently, dozens of people have visited the establishment to learn about this lesser-known side of the legendary actor, a two-time Oscar winner who tragically passed away at the age of 95, just a few meters from his wife, Betsy, 65.

“I saw them here once, a long time ago. The paintings are his, and she was involved in the menu because they were partners in the place,” says Malisa Aragon, a businesswoman who has been going to Jinja for years. Aragon was lucky. Sightings of the couple in the city were as rare as the passing of a comet. This is confirmed by Dom, one of the restaurant’s waitresses, who never met the couple, despite working there for eight years.

Not far from Jinja is Pandora’s, the interior design store Betsy Hackman (née Arakawa) founded 24 years ago, inspired by a knitted pillow Gene had brought back from a film shoot in Central Europe. She started the business with her close friend, Barbara Lenihan. The Lenihans were perhaps the Hackmans' closest friends in Santa Fe and knew them most intimately. “It’s all very sad,” Lenihan tells EL PAÍS. “Gene probably depended a lot on Betsy, and she on him as well,” she adds.

The Lenihans met the two after Gene Hackman filmed The Firm, directed by Sydney Pollack and starring Tom Cruise. While in a dive shop in Hawaii, where Arakawa was originally from, Hackman saw a map of the USS Arizona, the ship sunk by the Japanese in 1941 at Pearl Harbor, a tragedy that killed 900 American sailors. The map, Hackman learned, was made by Daniel Lenihan, an anthropologist specializing in underwater archaeology who also lived in Santa Fe. Back in New Mexico, the couples went to dinner, marking the beginning of a 30-year friendship.

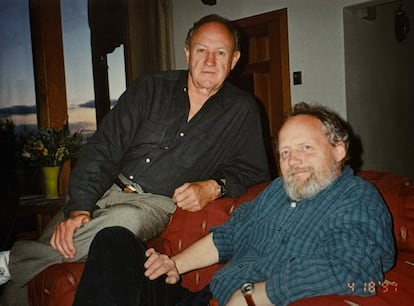

Gene and Daniel tested their friendship by delving into fiction writing. Together, they published three novels between 2004 and 2011, each acknowledging Betsy’s invisible but vital contribution. She interpreted Gene’s scribbles, compiled manuscripts, and offered advice. “She also keeps us from killing each other when we disagree,” they humorously admitted in the acknowledgments of Justice for None (2004), a novel about a World War I veteran wrongly accused of murder.

Barbara Lenihan isn’t surprised by the solitary life her friends led in their home on Old Sunset Trail, in a residential area of the Santa Fe Mountains. “They really liked their privacy. She was very competent and organized. They had someone to help them clean, but since there were only two of them, they didn’t need it as often. Maybe in the last year or so, they stayed home more,” she recalls. The last time a paparazzo captured the couple in public was in March of the previous year, as they left a restaurant in the city. Despite being together since 1991, only a handful of public images of the couple exist.

Lenihan last saw her friend and business partner in January, when she visited Pandora’s to buy some candles. Betsy was wearing a mask. She may have already been infected with hantavirus, a disease transmitted through rodent droppings and urine, with an average incubation period of 18 days. Unfortunately, Betsy Hackman was unlucky. The disease has a 43% mortality rate among the 129 patients who have contracted it in New Mexico since 1975. Of the seven cases in 2024, two people died. “If it weren’t for the virus, Gene would have lived a couple more years, and Betsy would have easily had another 30 years,” Lenihan reflects.

Kevin Morales, a former employee of Varment Guard, a pest control company, knows the Hackmans' property well. He visited several times to fumigate. “There are a lot of mice in the area where the house is located. They didn’t have any in their residence, but they did in the maintenance rooms, which were located elsewhere on the property. And these were connected to the central ventilation system,” explains Morales, who has fond memories of the couple. “They were very kind and always offered us lunch when we visited,” he says. In 2020, when the pandemic began, the Hackmans stopped calling the company.

Authorities believe Mrs. Hackman died sometime on February 11. Security cameras captured her that Tuesday morning as she shopped for food and medicine, including painkillers. The doctors who performed the autopsy believe she mistook the symptoms of her infection for those of the flu. Mrs. Hackman rarely used her cell phone but had spoken with Brendan, the Lenihans' oldest son, on February 8. He was expecting his second child. “Betsy was very excited about it, and my son thought he’d talk to her again soon. He didn’t,” Lenihan laments.

Mrs. Hackman preferred to communicate by email. Police found no messages sent or read after February 11. Veterinarians for the couple’s three dogs — Zinna, Bear, and Nikita — also unsuccessfully attempted to contact her by phone to notify her that food was ready for the animals. Zinna, a 12-year-old Australian kelpie who had recently undergone surgery, died at the couple’s side in a kennel. The dog’s full name was Zinfandel, a nod to the Hackmans' fondness for red wines, as it is the name of a grape variety.

Gene Hackman was inside the house and near his wife’s body for several days. The autopsy revealed that her heart, which had a pacemaker and a triple bypass to improve circulation, stopped beating on February 18, seven days after her presumed death. The report also revealed signs of advanced Alzheimer’s in his brain. Authorities believe he may not have realized Betsy had died. There was no food in his stomach, but his body wasn’t dehydrated. For their friends, however, the physical deterioration was more apparent than the mental decline. Hackman had lost a lot of weight in recent years, making him more frail. Until recently, he still rode a bicycle.

The case has shocked Santa Fe, a city where one in four residents is over 65. Stepping outside, it’s easy to notice the high proportion of gray hair and walkers among its 90,000 residents. Health organizations estimate that throughout New Mexico, around 67,000 people, like Betsy Hackman, provide unpaid care to 46,000 Alzheimer’s patients.

Hackman and his wife, Betsy Arakawa, met at a gym in Los Angeles, California, in the mid-1980s. Arakawa was the only child of a single mother who had a successful business career in Hawaii. She studied piano in Honolulu and, at the age of 11, performed in a concert for thousands of children. She attended the private Punahou School — the same elite institution from which Barack Obama graduated — and later moved to California to study social studies and communications. “I think she still played piano for them, but only at home. Her life was really about Gene, being a good partner, and helping him,” Lenihan recalls.

Hackman, who starred in iconic films such as The Conversation, The French Connection, and Unforgiven, was always private about his personal life. However, in 1985, during the promotion of Twice in a Lifetime, he shared details about the end of his first marriage to Faye Maltese. In an interview with the Florida Sun Sentinel, he said: “I did not leave my real-life wife for a younger woman. We just drifted apart.” He had three children from that marriage: Leslie Anne, 58, Elizabeth Jean, 62, and Christopher Allen, 65, the same age as Arakawa. Hackman did not include any of his children in his estate, leaving everything to Betsy.

Although Hackman and Arakawa did not have children together, they formed strong bonds with the descendants of their close friends. The Lenihans, for instance, cherish the memory of Brendan’s high school graduation. Brendan invited Gene to the ceremony, which turned out to be a memorable evening. Alongside Hackman were notable figures like physicist Murray Gell-Mann, Nobel Prize winner in 1969 for the invention of the quark; playwright and actor Sam Shepard; and author Cormac McCarthy.

After the event, McCarthy, who won the Pulitzer Prize for The Road, approached Hackman and invited him to lunch. Gene agreed, but only on one condition: he invited Brendan along, knowing that All the Pretty Horses, one of McCarthy’s works, was Brendan’s favorite novel. Barbara Lenihan remembers, “When we told him, he couldn’t believe it. It was his graduation present.” She adds: “All doors opened for Gene. And if you were with him, they opened for you too.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.