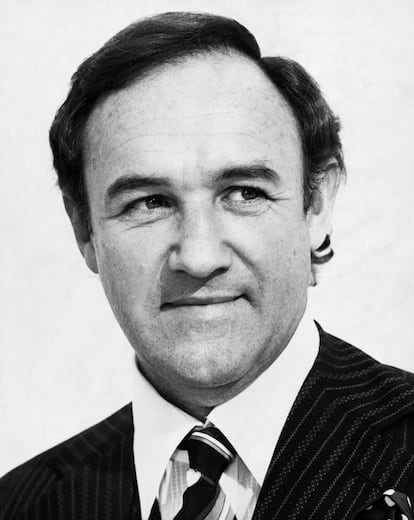

All of Gene Hackman’s Men

The recently deceased actor, a symbol of the New Hollywood movement, built his career on an extraordinary versatility that allowed him to play antiheroes, villains and ordinary guys

Gene Hackman’s first film role was in the heartbreaking Lilith (1964), Robert Rossen’s drama of love and madness starring Warren Beatty and Jean Seberg. Hackman was 34 years old and a single scene with a lot of dialogue, a one-on-one with Beatty, was enough to recognize the talent of an actor who was disconcerting and unique in his changes of register. Hackman seemed destined to be a character actor, but his ability to elevate his ordinary man look to great heights made him a star capable of moving with agility — just like his great role model, James Cagney, he knew how to act with his whole body — among characters of all kinds.

Hackman knew how to extract from each the greatest violence or the greatest tenderness; or both at the same time. He could embody a shady U.S. president in Absolute Power, the 1997 film by Clint Eastwood, or, with brilliant comic flair, the comic book villain Lex Luthor (“the greatest criminal mind in the world”) in Superman (1978).

Tall, with small, radiant eyes and an unfailing smile, Hackman began working in Broadway comedies and, above all, in television series. But Lilith and Warren Beatty changed his luck. The handsome leading man, a member of the first generation of the so-called New Hollywood, wanted Hackman at his side to play Buck Barrow, the older brother of outlaw Clyde Barrow in Bonnie and Clyde (1967), the film that rewrote, in the light of the 1960s, the myth of the young outlaws and of Hollywood itself. Hackman gave so much credibility and nuance to his character that two of the key directors of that generation, William Friedkin and Francis Ford Coppola, tapped him to star in two essential films in his filmography and in the history of the New Hollywood movement: The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971) and The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974). The first earned him his first Oscar; the second, the eternal glory of great actors.

Friedkin’s film presented Hackman as a cynical, tough and racist policeman, a type of evil character that made the actor uncomfortable, because it was very far removed from his own personality, but which he knew how to take advantage of and refine throughout his extensive career of almost one hundred films. The most perfect example of this is in another one of the fundamental works of his life: Unforgiven (1992), also directed by Clint Eastwood. His cruel sheriff Little Bill Daggett earned him his second Oscar and a new period of creativity until his retirement from the movie industry in 2004.

William Friedkin once explained that his approach to the actor during the filming of The French Connection consisted of long personal conversations prior to filming. Through these conversations, he discovered that Hackman’s greatest conflict, his Achilles heel, was his father figure (something that, by the way, also happened to Marlon Brando). Hackman spent part of his childhood in West Dundee, a small town in Illinois with a strong conservative and supremacist tradition, with ties to the Ku Klux Klan. The boy hated that environment as much as he hated his father. Resentment against any authority figure marked his entire youth and Friedkin, who wanted to exploit that hatred in the actor, knew how to bring it out.

But perhaps his best work, the most difficult and indelible, was his Harry Caul in The Conversation, Coppola’s film (premonitory in its vision of a world of tech surveillance) about guilt, paranoia, loneliness and, of course, sound. Playing that meticulous and taciturn man was not an easy job for the actor, as he was almost always isolated in the frames, almost always silent or distant. Invisibility was one of Harry Caul’s characteristics and Hackman internalized it in such a subtle and perfect way that his presence was forever etched in the memory of the viewer. With his trench coat, his glasses and his Catholic faith, Gene Hackman turned his character into an almost abstract antihero, capable of expressing the greatest sadness in the world with only the weight of his shoulders and back.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.