David Bowie, the galactic thinker who encouraged us to break new ground

The British musician touched on fear of technology, the disruption of binarism and constructing and deconstructing our identity

When David Bowie passed away on January 10, 2016, millions had the feeling of losing someone close even though they had not known him personally. This was part of the magnetism of this multi-talented pop icon who, according to his biographer, David Buckley, changed more lives than any other public figure: he opened our minds to the possibility that it was okay to be different, to sit outside of the norm.

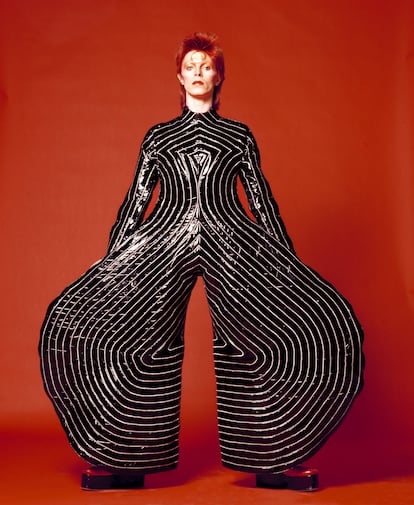

Now, a decade after his death, Bowie’s star still dazzles. In the UK, Alexander Larman’s Lazarus: the Second Coming of David Bowie has just been published, and Movistar Plus will premiere the documentary David Bowie: The Final Acton on January 9. Bowie classics such as Space Oddity, The Man Who Sold the World, Changes, Starman, Ziggy Stardust and Heroes still get plenty of airplay while his albums, whose covers are portraits of his face as mod, alien, Hollywood celebrity, rock star, female model and Diamond Dog-hybrid, still take pride of place in personal record collections. In short, Bowie’s cultural and social footprint remains indelible.

Ahead of his time, Bowie spoke of post-apocalyptic landscapes, of isolation, of the technological journey beyond the human realm — posing the great question of our time: Is the planet going to survive? He talked of dynamiting binarism and making room for different notions of identity, while forging a deep and warm bond between those who listened to him. Because beyond pessimism, his songs reveal two things, as the philosopher Simon Critchley writes in his book Bowie: one is the hope that we are not alone and the other, that it is possible to escape from this place, even if it’s for a day.

In his multiple phases, Bowie addressed the fragility of being by embodying the adolescent, the madman, the ghost, the degenerate ascetic, the android, the addict, the father, the friend, the brother, the human. And he opened an infinite number of doors “For me, for you. For us,” wrote British journalist Suzanne Moore in The Guardian. “He gave us everything. He gave us ideas, ideas above our station. All THE ideas and a specific one. Of life. The stellar idea that we can create ourselves whoever we are.” He achieved a personal and, at the same time, collective connection, especially among the marginalized young — among those who consider themselves different, misunderstood, rejected. “Bowie bridges the gap between the secret and the public. He is a person who works with words and produces effects. He was also the first to say: I’m weird, so what?” Uruguayan writer Ramiro Sanchiz, author of David Bowie, sonic posthumanism tells EL PAÍS.

Bowie’s successive personas represent the great masquerade: the “authentic”, in fact, does not exist, and everything is influence, copy and simulacrum. “Bowie assumes that the self is a fiction, and that every biography is nothing but a polyphonic novel,” says Sanchiz, who has Bowie on his list of “agents from beyond” along with the writers H. P. Lovecraft, J. G. Ballard, Kathy Acker, the philosopher Donna Haraway and the film director David Lynch, with whom he worked on Twin Peaks. Sanchiz is fascinated by those who reveal the dark, stranger side of things, those who dare to push the boundaries and “infect us and usurp everything we think we are and make us understand that we have nothing.”

Bowie breaks our chains and frees us. As his beloved Little Richard did earlier — a poor, lame, Black and gay boy who decided to come out in the 1950s when the U.S. was awash with racism, super macho attitudes and an obsession with money — Bowie redefined what was considered “natural”. According to Critchley, “What defines Bowie’s music really well is the experience of longing.”

Byron and the Enlightenment

“Music doesn’t play a big role in my life,” Bowie said in a 1976 Playboy interview, speaking during his Thin White Duke phase, marked by a crazy fondness for cocaine. He claimed then that recording songs was just a way to make a living, and that his true passion was knowledge and the “survival of the soul.”

We will never know to what extent that is true, but the truth is that Bowie was an avid reader: he once defined himself as “a born librarian with a sex drive.” He studied Buddhism, read Carl Jung, Nietzsche, Albert Camus, and probably also some figures from the British Enlightenment, who raised the possibility that consciousness was a construct. Famously, George Berkeley said “esse est percipi” — to be is to be perceived — which opened up the possibility of the human being coexisting with two identities: a revolutionary notion that could imply that “people do not have a real self, or that they have several selves, or that they had no self, but only a series of sensations and responses,” Emily Bernhard-Jackson, professor of literature at the University of Exeter, tells EL PAÍS. “Identity became confusing and questionable, and I think David Bowie was reflecting on these very possibilities.” Bernhard-Jackson is the author of several articles about Bowie: in one she likens him to Lord Byron, because both use their work to explore the meaning and construction of identity.

Like the beatniks he admired — Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, and Neal Cassady — Bowie perhaps also believed that the critical spirit of the Enlightenment could be traced back to the theories of Hegel and Marx. “He reproached the positivists for having killed the true spirit of the Enlightenment, by stifling its fundamentally negative dimension,” according to Bernhard-Jackson, who also glimpses in Bowie hints (conscious or not) of Herbert Marcuse; Marcuse believed that the struggle against alienation could only be addressed by those marginalized by the system.

Perhaps it is time to recognize that disharmony with the world is an identity and a way of existing as good as any other; that we can expand the limits of what is possible. Bowie’s son, filmmaker Duncan Jones, recently explained on Instagram that one of the things he admired most about his father was his ability to reduce a roast chicken to a dry shell, sucking every last drop of marrow from every bone. Bernhard-Jackson reflects: “This image of Bowie is completely different from the one most people have of him. However, this was also his identity: father, chicken lover, very hungry man...” You never know someone completely. To imagine Bowie devouring a chicken, flying in a space capsule, or reading in his slippers is to live accompanied by a mysterious, absolutely incandescent star.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.