Forty-one cities, 96 beds and my toothbrush: what I discovered after leaving my home to live from hotel to hotel

Inspired by Oscar Wilde and Agatha Christie, the author decided after a break-up to test the theory that being constantly on the move would cushion the blow. He found it was halfway true

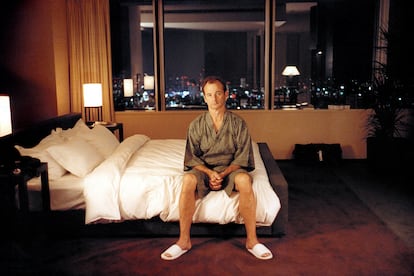

More or less three years ago I gave up my search for a rented apartment in Madrid and I went to live in hotels. I still haven’t decided if it was a good idea or not, but at least I think I have a better idea of what is so special about this vicarious kind of life that some of my favorite writers, finding themselves fallen on hard times, also sought refuge in. Oscar Wilde, for example, who after three years of exile in hotels in France and Italy, died fighting a “duel to the death” with the wallpaper of his Paris boarding house, which is now a luxury hotel. Or Agatha Christie, who after discovering her husband’s extra-marital affair hid away for 11 days in the Old Swan Hotel in Harrogate, during which Scotland Yard, 15,000 volunteers, Colonel Christie, several aircraft and a clairvoyant to whom Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had presented one of her gloves searched high and low for the author.

In my case, the trigger for my years of hotel living was an explosive mix between a break-up, the difficulty of finding another apartment in the capital and the license I have by being able to earn a living from anywhere on the planet with a decent internet connection.

Why on earth was I going to hand over all my money to a Madrid landlord who would scrimp on every cent if my refrigerator breaks instead of the concierge of a Palermo hotel who will wish me good morning and call me “sir” when he sees me? Convinced by the prospect of such occurrences, in 2018 I touched down in Syracuse, Sicily to hang my hat in one of those hotels with angels painted on the ceiling of the breakfast room. It was the first stop on my grand tour, that journey that the young students of the Enlightenment undertook over months or even years to complete their education and that, rather than learning how to form a considered opinion on a Tintoretto, I sometimes think I conducted purely to have some kind of ordered way of linking together all of my hotel stays. Recently I did the numbers: over the last three years, I have slept in 96 hotel beds in 41 cities.

I am fully aware that making a list of hotel reservations given the problems my generation face in trying to get on the property ladder or even find a half-decent rental sounds like a fairly crazy idea. It is, and several of my friends who know I am no millionaire said as much when I floated the idea of my grand tour, comparing it to an escapist stunt. However, I am now convinced that in many ways hotel life is more authentic than domesticity. For anyone who has suffered a relationship disappointment as severe as Agatha Christie’s and who no longer believes in the word “home,” I would go so far as to say it is recommendable.

I’m thinking about the house I shared with my ex: we lied to each other by allowing ourselves to believe it would last forever and duly filled it with things. Hotels have never misled me, and they will never mislead anyone else.

As comfortable as I felt in that first hotel in Sicily, nothing about my room gave me the urge to fill it with plants and little vases, and I found in it no more empty space than what was necessary to store my clothes, my toiletry bag and the book I was reading, all of which are easily transported from one place to another and that do not tie one down with sentimental value to one place or another. On the last day, I picked up my bag and left. The concierge did not make a scene when I said goodbye and handed him the key, and I did not get upset when I saw him hand it over to an Italian who was better-looking than me.

Hotel rooms know all of this and they also do not allow themselves to be misled by guests who end up leaving them sooner rather than later. All of them possess a feline quality that refuses to be domesticated.

If, for example, I move a night stand that is bothering me, the following day when I return from visiting a museum or whatever, I find that it has obstinately returned to its rightful place. The room does not tolerate my disorder, nor does it allow my tastes or obsessions to have an influence on it. I hide the awful painting above my bed in the closet and the room thumbs its nose at this artistic critique, putting it back in exactly the same place as soon as the chance arises. Finally, the time for parting comes and I leave the room. The swan-shaped towels that charmed me on arrival will be there to greet the next guest and the glass in the bathroom will be freshly enveloped in its sanitary plastic cover to be presentable for receipt of the next toothbrush. Is there any better course of action for someone whose heart has just been broken to place their faith in?

Naturally, hotels prefer to sell themselves as places of escape rather than as a kind of spa for tortured souls. Maybe they are when you only stay in them for a bank holiday weekend. However, living from hotel to hotel does not offer a ticket to escape from reality. In fact, I believe that there is no other way to more intensely appreciate the melting pot of mankind than by moving from hotel to hotel, and I am not just talking about the notion that hotels are some kind of miniature Tower of Babel where one is woken up by the shouts of a Danish couple one night and the snoring of a Swiss the next.

Who was it that made that beautiful remark, for example, that history is nothing more than silk slippers going down the stairs as muddy, nailed boots stomp up them? This truth, which Louis XVI only became aware of when it was already too late, is one I learned in fewer than 12 hours on the only occasion I managed to get a room in a decent hotel in Venice. It was in October 2018, when three-quarters of the city was underwater during the worst floods in 50 years. Seeing that the water was lapping around people’s ankles, I left the café where I was writing and returned to my hotel, soaked to the same part of my leg, then up to my knees, then to the thighs. My little hotel with views of the Grand Canal was also flooded. From the other side of one of the metal shutters Venetian businesses use to protect themselves from the acqua alta, I shouted for my bag and canceled the rest of my reservation. Then I walked with 20 kilos of luggage on my head and my iPhone gripped between my teeth to Santa Lucía station. There I got on the first available train. It was destined for Milan.

During the journey, I looked for a hotel to spend the night in. I remember they were all extremely expensive (I think the following day was All Saints’ Day) and that it took so long to find one that I liked and that wouldn’t blow my budget that my cell phone battery died. When I arrived in Milan, I had no choice but to present myself at the first hotel that didn’t look too pricy. Perhaps I went a little too far in ensuring that outcome, and that is where I learned Louis XVI’s truth: I had woken up that day in a room with silk curtains and went to sleep on a bed with cigarette burns on the mattress, in a dump that stank of Venice’s canals courtesy of my sodden pants.

Something similar has happened on many occasions when I have tried to extend my stay in a particular hotel only to find that day coincides with a soccer match or a medical conference and the prices have gone through the roof, forcing me to seek more modest accommodation as though my shares have suddenly plummeted. On other occasions the opposite has happened: I have arrived out of season in a city like Biarritz and become The Great Gatsby. Living from hotel to hotel accustomed me to twists of fate. To saying goodbye to everywhere. That the old wooden elevator I have become fond of will maybe never guide me to bed again.

Moving from hotel to hotel also brings about a very beneficial phenomenon for those who have suffered a cruel blow.

Before I embarked on this wandering existence, like most people I thought that entertainment and novelty made the hours fly past, while monotony and boredom slowed the clock. It’s a notion that, thinking about it now, is planted in one’s head when returning from a vacation with the sensation that you’ve been gone for five minutes and that while away time was somehow accelerated. Now, though, I know that when these sensations of new experience are constant and not interrupted by a return home, exactly the opposite is true: time thickens and a year with many changes seems to last twice as long as a monotonous one. As such, every time you wake up in a different place that period of time experts recommend we place between ourselves and something that has hurt us widens. I believe that if Agatha Christie boarded the Orient Express shortly after signing divorce papers it was not only because Baghdad was a long way from Colonel Christie, but also because with every week of travel she gained two of forgetfulness.

In February 2020, I was following in the footsteps of Lord Byron and other travelers in Spain and Portugal when the worst bout of flu I have ever experienced laid me low in a Lisbon hotel bed for almost a week. I admit that during those fevered days I missed having a kitchen to hand because it was hard work crawling up the steep streets in search of bananas and sugarless yogurt. A few weeks later, the coronavirus lockdowns began. My grand tour around Europe became several months in my parents’ house, a sobering destination for anyone who has been on an adventure. “I’m an idiot. As soon as I can I’m going back to Madrid to look for an apartment,” I thought many times as I lay on the narrow single bed that had survived my adolescence. That said, now that I’m about to get vaccinated, I think I’ll spend a bit more time in hotels. After so many months of suspecting everyone and fearing every loose sneeze, it will be worthwhile to be back among these families of strangers.

English version by Rob Train.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.