Black, gay and the true king of rock and roll: This is how Little Richard set the tone for popular music

The documentary ‘Little Richard: I Am Everything’ tells the story of one of the most influential, conflicted and unrecognized musicians of the modern era, mentor to the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix

Mick Jagger slept on the floor of his room, Paul McCartney took lessons to scream like him, and Elvis Presley recognized him as the true king of rock and roll. However, Little Richard never reached the huge commercial and popular magnitude of his most famous pupils. “You should all be fighting to make me an album. The greatest singers that ever lived have been with me, Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, the Beatles, Mick Jagger... Mick, you remember that?” he said jokingly, but very seriously, before the industry’s top brass in 1989, on the occasion of Otis Redding’s inclusion in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

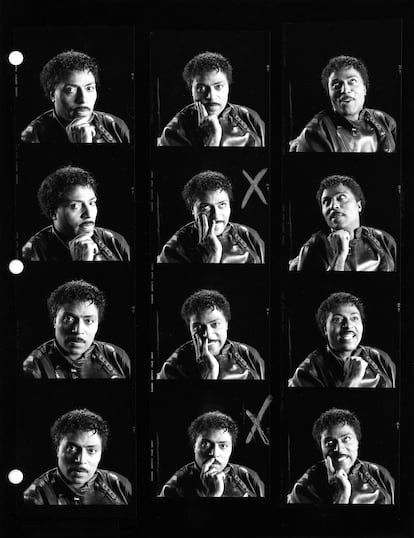

His legacy is honored in the documentary Little Richard: I Am Everything, released last year, which goes over the singer’s biography, his crucial musical contributions and the groundbreaking nature of his figure. The fact that rock and roll was a synonym for rebellion had a lot to do with the fact that one of its main architects was a Black, notoriously homosexual man who performed in the racist, homophobic southern United States of the 1950s.

“Figures like Little Richard or Esquerita have been excluded from the history of rock and roll for a long time,” says Lisa Cortés, the director of Little Richard: I Am Everything, via video call. “Telling the stories of the Black and queer population is often difficult, because they contradict the official narrative. In this case, it happens with Little Richard and the story that Elvis was the father of rock and roll.” The documentary shows how Little Richard’s hits used to be immediately covered by white artists like Pat Boone, who based his career on adapting songs by Black musicians, like Tutti Frutti, toning them down to adjust them to what was socially acceptable in the era of racial segregation. To capitalize, too: Boone made a fortune (only Elvis Presley sold more than him in his time), while Richard barely received royalties for the new versions. The frenetic pace of songs like Long Tall Sally was in fact a strategy by Little Richard to boycott Boone, who could not sing at that speed.

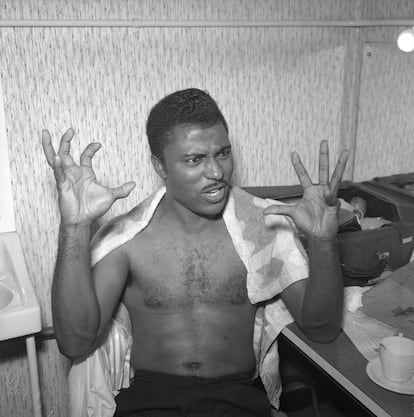

Born and raised in Macon, Georgia, an American southern city that served as the official arsenal of the Confederacy during the Civil War and where lynching Black people was a regular occurrence, Richard Wayne Pennyman was the third of 12 siblings (seven boys, five girls) and had a difficult relationship with his father due to his homosexuality and his taste for makeup and feminine clothing. The song that launched him to fame, Tutti Frutti, was originally about anal sex, before being conveniently rewritten for the studio version after producer Bumps Blackwell heard it live and instantly recognized it as a hit. The opening war cry (a-wop-bop-a-loo-bop, a-lop-bam-boom!) and Richard’s wild pounding of the piano became music history, and the song established what would become the rhythmic standard for rock and roll.

“What made Little Richard a genius was his gift for mixing parts of blues, gospel and other different means of expression in his music, all combined with his queer side. That someone in 1955 was able to make such a unique recipe is impressive,” reflects Cortés. The artist, who found a school in church music and who first went on stage by invitation of the evangelical singer and guitar player Sister Rosette Tharpe (whom he idolized and who is considered a foremother of rock and roll), gave some of his first performances dressed as a woman, under the name of Princess LaVonne. In an archival interview that appears in the documentary, Richard states that he used to exaggerate his effeminateness so that white men would not see him as a threat to their women and he could perform in their venues. “He certainly believed so. But it doesn’t make much sense,” says the director. “Those environments were also very homophobic; he even got arrested because they considered his behavior indecent.”

Call me Reverend

Little Richard’s life was greatly conditioned by the guilt he felt regarding his sexuality. At the height of his success, when he was selling millions of copies and selling out venues all over the country, the singer decided to give up rock music in order to study theology, married a woman and asked everyone to refer to him as Reverend Richard. At that time he released some gospel albums, such as the double-LP Pray Along With Little Richard (1960), and refused to perform any of songs that made him famous, like Lucille, Keep A-Knockin’ and Good Golly, Miss Molly, as rock and roll was, he explained, far from the divine.

However, his jealous, competitive nature would lead him back to his usual songs in 1962 during a European tour with Sam Cooke, after he saw the public’s enthusiastic response to his fellow performer. After that came his famous alliance with the still inexperienced Beatles, whom, grateful for their admiration, he taught, advised and sponsored. With them, he shared the musical season in Hamburg that consolidated the British band.

After divorcing his wife, Richard once again admitted his homosexuality, although, far from normalizing it, he often made it clear that his inclinations seemed impure to him. In 1982, in an interview on Late Night With David Letterman, he once again rejected his orientation, stating that “God created Adam to be with Eve, not Steve.” He also publicly acknowledged his drug addiction, joking that they should have called him Little Cocaine. In the book The Big Life of Little Richard, by Mark Ribowsky, readers can glimpse other dark sides of the singer, such as his toxic working relationship with Jimi Hendrix, who was his guitarist for a while and whom, according to the musician’s then-girlfriend, Richard sexually harassed. “Bad pay, lousy living and getting burned”; this is how Hendrix would later summarize their collaboration. According to the book, the star was tyrannical with the members of his band, whom, among other guidelines, were forbidden from smiling on stage.

Rediscovered by a new generation in the era of psychedelia, and later reinvented as an amiable figure that frequently appeared in galas, television shows and movies, Richard maintained contradictory, changing stances during the 1980s and 1990s. Filmmaker John Waters, who appears in the documentary and claims that his distinctive thin mustache was inspired by Little Richard, interviewed him in 1987 for Playboy and sparked the singer’s anger for making fun of his alleged heterosexual rebirth; still, given his need for attention, Richard was flattered when the text was published. He also enthusiastically attended various award ceremonies in the 1990s, when he suddenly received all the honors that had been denied to him — like many other Black performers — throughout his career.

“There are many contradictions in the figure of Little Richard. The thing is that he spent his whole life navigating that gray area, through popular culture and transgression,” explains Lisa Cortés. Ringo Starr, Brian Wilson and Keith Richards publicly paid tribute to him upon his death in 2020, and Baz Luhrmann’s film Elvis (2021) gave him the place he deserved in Presley’s story, clearly showing the influence that the African-American singer had on his music. Due to his final controversial appearances in ultraconservative Christian media, Waters, for his part, lamented that Richard died a homophobe, saying terrible things about the gay and trans people. Regarding whether the singer managed to make peace with himself, Cortés says, one can only speculate. “What is certain is that, in those last days, his most important relationship was with God. He felt like he had no one else,” she says. Regardless of religious beliefs, the documentary (available on Max) proves that Little Richard, in one way or another, more than managed to transcend.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.