‘Leave your egos at the door’: The unique night when 80s pop icons recorded ‘We Are The World’

The new Netflix documentary ‘The Greatest Night In Pop’ examines the making of one of the world’s most famous hits

If we mention We Are The World to anyone over the age of, say, 40, the reaction we are likely to get is either of derision or simply guilty pleasure. What remains in the collective memory is, above all, the image of all those ‘80s pop superstars singing their hearts out in unison, at times with hands over headphones. It is an image that has since been parodied a thousand times.

Back then, however, it was a major milestone in pop history; an initiative of epic proportions in which anything and everything could have gone wrong. Nowadays, in an era in which most artistic collaborations are done remotely, it would be unthinkable to see almost 50 of the world’s biggest pop stars recording in the same studio. That they would do so for a purely altruistic cause, without any single star trying to impose their own conditions or preferences over the others, seems even more improbable.

The Netflix documentary The Greatest Night In Pop released Monday, January 29, following its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, looks back at that memorable event, with singer Lionel Richie as executive producer and narrative voice. Vietnamese-American director Bao Nguyen was privileged to have footage of virtually the entire recording process, allowing us to become flies on the wall. The documentary also features some of the night’s stars airing their memories of it in interviews recently recorded in the A&M studios in Los Angeles where the 1985 recording took place.

The first thing to remember is the recording was inspired by its forerunner, the charity single Do They Know It’s Christmas? The brainchild of Bob Geldof, this single brought together another glittering cast of stars from the British and Irish worlds of pop to raise money for victims of the famine in Ethiopia that was making headlines at the time. Dubbed Band Aid, it involved big names like Bono, Sting, George Michael, Boy George, Paul Weller, Phil Collins and band members from Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet, and it took Christmas 1984 by storm to become the best-selling single of all time in the U.K. It was the musician and actor Harry Belafonte, known for his civil rights activism, who flagged up the following discrepancy: how was it that a bunch of white people had organized themselves to help a region of Africa and their African-American counterparts in the U.S. had not? Belafonte then contacted Ken Kragen, then one of the most powerful men in the American recording industry, and with a lack of political correctness typical of the 1980s, said: “If Jews were starving in Israel, American Jews would have raised millions of dollars by now.” The first step was to involve the most important African-American musicians of the era: Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder and Lionel Richie, as well as Quincy Jones, the star producer who had made Thriller the best-selling album in history.

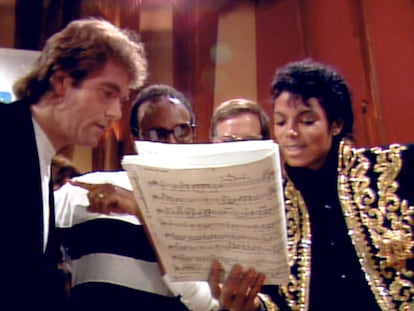

The documentary shows a clip of the initial compositional process involving Michael Jackson, Lionel Richie and Quincy Jones. Apparently, they were unable to contact Stevie Wonder as there was no email or cell phones in 1985, but he showed up anyway at the studio. One of the interesting revelations in the documentary is the fact that Jacko didn’t know how to read music and explained all his musical ideas by humming.

The end result was basically a Jackson creation, and the first demo was recorded with the help of several session musicians, providing a template for the final recording, which would be signed by USA For Africa, the name of both the organization created for the occasion and the band that would perform it.

As soon as Kragen, Jones and company put out the call for collaborators, names started to flood in: Ray Charles, Tina Turner, Diana Ross, Smokey Robinson, to name but a few. But the one that changed the course of events was Bruce Springsteen, followed by Bob Dylan and Paul Simon. It was realized that the project could be more ambitious than had initially been thought, involving both Black and white stars from the worlds of soul, pop and also rock. The inclusivity would make the project more powerful. The idea was to have all the artists together in the same studio — no mean feat given that the organizers were dealing with some of the most demanding schedules in show business. Finally, it was decided to bring the collaborators together on the night of the American Music Awards (AMA) in Los Angeles, as the awards were being hosted by Richie and many involved would be there.

Special emphasis was placed on keeping the contents of the demo and the location of the recording secret. The slightest leak could mean being swamped by fans or paparazzi, which would scare off the stars. During the 10-hour recording, there was a lot of finetuning to be done with the vocal arrangements, and careful consideration was given to each artist’s position in the room, who sang which line and with whom, as well as vocal ranges and how to sequence them so that the emotional potential was maximized. “We make a circle in the room and have everyone looking at each other,” said Quincy Jones, whose idea it was to hang a sign at the entrance of the studio that read “Leave the ego at the door.”

Presences and absences

Were the 46 biggest American pop stars in that Los Angeles studio? No, not all of them. Prince and Madonna were not among them, even though they had performed at the AMA’s ceremony. The organizers had reserved a slot for Prince, who had beaten Jacko in several award categories that night, but he never turned up. There was speculation that this was due to fierce rivalry between him and Michael Jackson. But another theory put it down to the extreme shyness of the Minneapolis genius, who avoided hanging out in crowds. In the only non-congratulatory moment in the documentary, Sheila E, a collaborator of Prince at the time, reveals that after feeling pleasantly surprised at being invited to the recording, she realized that, in reality, she was being used as bait to convince Prince to come; she was asked to phone his hotel in the middle of recording to no avail. Prince would not be persuaded, suggesting only that he could play a guitar solo in another room. Quincy flatly refused: everyone had to sing, and sing together — although he made an exception for Jackson, who recorded his first solo lines while the others were still at the AMA’s.

Madonna’s absence is not so closely examined in the documentary, perhaps to cover up what may well be the biggest casting error in pop history. One of the organizers had suggested that they could have either Cyndi Lauper or Madonna, whose Like a Virgin album had been on the market for two weeks and already had a single at number 1 and another at number 2. They could not, it was said, have both singers at the same time. As good as Lauper was, it was an unfortunate decision.

With those stars who did collaborate, Quincy’s ego slogan appeared to work. The most striking thing about the footage from the recording is that those involved appear to be stripped of their usual self-importance to the point of bashfulness, “as if it was the first day of kindergarten,” says Richie. Many of them met for the first time there, and even signed autographs for each other. Among them, Dylan appears totally out of place. When everyone sings the main chorus, he simply moves his lips, as though embarrassed and visibly uncomfortable, like a child who has been invited to a birthday party and doesn’t know how to fit in. It was Stevie Wonder, one of the night’s heroes, who broke the ice by dragging Dylan to his piano, mimicking his voice, and giving him ideas on how to approach his line of the song.

Stevie Wonder also proposed incorporating some Swahili verses into the song, albeit without much success. Someone shouts, “Stevie, they don’t speak Swahili in Ethiopia!” Bob Geldof, who was present at the recording in a sort of advisory role, said memorably, “We are not singing for those who go hungry, we sing for those who have the money.” The documentary does not feature the moment when, according to several witnesses, two Ethiopian women appeared in the studio to thank the musicians. They had been invited by Stevie Wonder.

Pop anthem or functional tool?

When We Are The World was released on March 7, 1985, it automatically became the global super-hit it was destined to be, but the song also received a lot of criticism. The most stinging came from the reputed music critic Greil Marcus, who said the song sounded too much like a Pepsi jingle — a company that, at that time, sponsored both Jackson and Richie. It was, of course, a very easy song to ridicule for its syrupy melody and church-like chorus, not to mention the imperialist vision of the U.S. as savior of the world; it could also be viewed as nothing more than a sticking plaster that served to wash consciences while not daring to go to the root of the problem of hunger, or to question the responsibility of Western governments and big business regarding it.

Bruce Springsteen addresses the criticism in the documentary, saying, “People judged the song aesthetically, but it was just a tool to try something.” In the light of this, we can shrug off the cynicism and acknowledge the fact that We Are The World fulfilled its function. The single raised even more money than expected, which, according to the organization, amounted to the equivalent of more than $150 million. With that money, more than 70 recovery and development projects were launched in seven African countries, including aid in agriculture, fisheries, water management, manufacturing and reforestation. Training and birth control programs were also developed, while 10% went to help the homeless in the U.S.

The success of We are the World initiative prompts us to reflect on how both the stars involved and the public were swept along in the belief that a song can change the world; how they trusted that a physical record, a simple single, would be able to sell enough copies to satisfy the hunger of a continent. It was a show of muscle from the pop world, whose social relevance at that time is difficult to grasp today. It was also an example of humility and disinterested collaboration — no one was paid — between musicians at the peak of their careers at a time when Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher had made individualistic values and radical economic liberalism hegemonic.

The idea that pop could safeguard global consciousness would go from strength to strength, first with the 1985 Live Aid macro-concert and subsequently with solidarity albums and festivals that mushroomed in the years to follow, some turning out to be better than others. But, today, We Are The World remains among the top 10 best-selling singles of all time while the USA For Africa website is still active, and still raising money.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.